The making and baking portion of the bread assignment took place in the Kitchen of #5B 3260 Henry Hudson Parkway, Riverdale, New York.

09.25.17 - 09.26.17

Instructions:

Pamela Smith's verbal instructions on feeding sourdough

Ingredients:

Sourdough starter

Flour

Water

After the initial bread making fiasco of 09.24.17 (in which the starter was NOT fed but merely added to a recipe) I began to feed my started (very late) on 09.25.17 at 3:30 pm. I emptied the entire container into a metal bowl, and then added 1 cup of water, and 1 cup of white flour (per Smith's instructions). I then mixed the ingredients.

The mixture was left to sit for 12 hrs. Unfortunately, having had a few nights of bad sleep, I couldn’t wake up at 3:30 am, but instead woke up 7 am, halved the mixture, one of which went into a container, and another remained in a closed bowl, on 09.26.17. Both were refrigerated

09.28.17

Instruction:

Pamela Smith's verbal instructions on feeding sourdough

Emma Le Pouesard's "Pain, Ostie, Rostie, Bread in the Early Modern Europe" Annotation

John Evelyn's Recipe Manuscript

Ingredients:

Sourdough starter

Flour

Water

I came back to the bread assignment on 09.28.17. I settled on the recipe by John Evelyn, and began to transcribe it at 12:45 pm. The transcription took 5 ½ hours.

I am happy that I decided to do my own transcription rather than rely on a new updated version on the web. The wording was modernized, and lost a certain charm and spirit that is natural to older works. It felt also more authentic to rely on the original document, indeed to substitute a close transcription when an original is readily available seemed wrong.

When I read through the recipes for Household bread and Pain de Bourgeois, I found the latter lacking in directions, and the former in quantities, so I decided to combine the two, minus the rye flour typically used for Household bread.

The recipe for household bread read as follows:

"Of this take a Bushell about ten o’clock at night, and put Levin into it covering it with some of the same meale.

To temper it in winter, make the water as hot as you can indure it w[i]th the hand; In summer, it is sufficient it be luke-warme; so proportionately in the spring, & autumn.

The next morning early, Levin the rest of the meale, tempering & kneading it a very long time, until it be pretty stiff, for though the softer, more light & more bulky it appeare; yet it will be lesser tasting; the light bread goes faster away than that which is wrought [close]:

The bread well kneaded, you shall [turne] it in the Trough, laing the bottom upmost; then thrust your fist in the middle of the dow to the very bottom of the trough in 2 or 3 places, then cover it well with meale sacks & clean blankets."

At 9:12 pm, I took the mixture I had already fed and halved on 09.25.07, and once more fed it, adding a cup of water and flour each (as per P. Smith’s instructions), and let it sit until the morning as directed by Evelyn’s recipe. For Evelyn, I only followed his timing and water instructions, and also those very loosely, but for myself, I deconstructed those instructions all the same.

“Of this take a Bushell”. I knew "Bushell" was a measurement, and from prior knowledge, as well as Emma La Pouesard’s annotations, it referred to flour. The word “meale”, from reading the rest of the recipe seemed to imply the sourdough that is then turned into dough and baked into bread. Evelyn’s fluid use of the word “meale” at times confuses. But having read Pouesard’s annotation, I knew that bread was primarily made of “flour and water, often with yeast and salt added” (7).

Immediately proceeding the recipe for flour, came water instructions. In the introductory set of instructions to the manuscript, Evelyn takes pains to emphasize the quality of water used, which prompted me to take particular care with water in my second starter feeding session. He writes, “Water is so principal an ingredient to the making of bread that the goodness of that much improves it. This is very evident in pains, that bread wh. is made in imitation of the of Gonnesse though by the same baker & with the same corne, never succeeds, neither as to the colour or goodness, equal to that wh. is made upon the [plan] itself: this wholly imputed to the excellency of the water.

That water is esteem’d best, wh[ich] is lightest; or you may make a good experiment by tryals w[i]th several waters, as that of the River, fountain, well, or Rains. Those [which] will easily [1 word illeg] you to the best.”

Thus, to feed my starter the second time around, I boiled sink water, let it cool until it achieved the desired temperature of "luke warme", only then had it poured into the starter. I made it slightly warmer than "luke-warme" because although weather outside my kitchen was 29+ C, inside it was set to a cool 72 F. I did not take these steps in the first starter feeding session. I did, however, use warm water, having remembered my mommy always using warm water when baking bread.

09.29.17

Instruction:

John Evelyn's Recipe Manuscript

Xiaomeng Lu's Field Notes

Ingredients:

Sourdough starter

Flour

Water

I got to my starter bright and early, at 7:16 am, the kitchen smelled of freshly fermented dough, and as pictures will prove, it had slightly foamed, coated by tiny bumbles unevenly formed across its surface.

I set the oven to warm at 350 F, as Evelyn spent a great deal of time describing the conditions of the oven that must be met before the bread is to be put in to bake (more on this below).

I halved the leavened starter again, one half was put into a container to be used later, the other I set to work on.

I then looked to the recipe for Pain de Bourgeois:

"Take the 6th part of wh. quantity you intend to make, and put Levin into it; making a hole in the dow as you were directed when the masse is risen, cover it with as much more flower as water was at first; & leave it to rise againe; this ready, add to it the residue of flower, tempering it with water, kneading, & allowing it time to rise in every particular [3 words illeg] as has already been describ’d"

I first began by counting off 1/6 of the meale, to determine how much flour to use, obviously my assumptions did not include the initial contents of the starter began by Smith. So I made the assumption that everything done by Smith was irrelevant, and only my flour and water additions were to be counted. This led me to conclude that I would be need 4.5 cups of flour (calculation below). For my purposes, this would yield too much bread, so I went back to the recipe, and decided to follow the descriptive instructions that called for flour and kneading until the dough was stiff, tempering it with water. I ended up using about 2 cups of flour to 1/3-2/3 water. Again, I was careful with the water used. I had also decided to add a pinch of salt, on recommendation from previous students’ files.

The Household bread recipe advised that I thrust my fist into the stiffened dough in two or three places, which will leave physical markers, indents, to see if the dough had risen enough to be baked. I enjoyed that part a lot. There is nothing like the release that comes from punching something. I then proceeded to wrap it up, warm and cozy. I used a plastic bag to cover the dough tightly, and then 3 kitchen towels to layer it. This was called for by the recipe, but also comes from childhood memories of my mommy doing the same. Good times. I then cleaned my baking area, washed the dishes, and forgot to record the time I smothered the dough. So, I’ll estimate it to be at about 7:50 am.

At 9:24 am, I peaked at my dough, to see if it rose, and it indeed did. The holes I have punched into the dough have all but closed, and swelled. On very few occasions have I known such happiness.

I had read Xiamoneg’s annotation notes, and he saw a notable difference in the bread with repeated leavening. So I once more added flour, and a bit of warm water, and mixed and kneaded the dough. I then punched in the dough, this time in one area, made a significantly noticeable indent, covered it with a plastic bag, and three layers of towels, at 9:40 am.

I raised the temperature to 400 F, as the Evelyn recipe describes in detail just how hot the oven must be:

"Your oven hot (known by raking the end of the a stick against its roofe or hearth, if the sparkles rife plentifully) make it very [cleane], referring only a few coals nearer the mouth; lastly wipe it with a [mop] wett & wrung; then close it up a while to allay the [1 word illeg] heate & dust, wh. will endanger scorching; & when the fiery colour is a little abatted, let in your loaves as fast & quick as possible; ranging the biggest towards the upper end, round about and filling the middle spare last of all. He the heater [of] the Oven must be careful that he burne his wood in every part while kindling it sometimes at one side, sometimes at the other & continually scrapping away the ashes with his [1 word illeg]."

Ultimately, I felt 350 was just not hot enough. I then did a quick google search for baking bread, and it specified 400 to preheat, but to bake at 375. This I thought also loosely translated into Evelyn’s directions of heating the oven but then repositioning the coals to get a specific heating effect.

At 11:40 am, I checked on my dough, and it rose and expanded considerably the second time around. I proceeded to make bread loafs. And to prepare for baking.

I decided to improvise, and coated the dough forms with yolk, to give them a nice colour. The original recipe I selected did not call for it, but other Evelyn recipes did. Anyway, If I had nothing to show for this baking session, at least the final product should be pretty. My decision to add a yolk coating was purely aesthetic in intent.

At 11:50 am, the oven was heated to 400 F, and then I entered the tray, uncovered into the oven, and adjusted the temperature to 375 F. I set the time to 15 min, so as to check on the bread on Evelyn’s directions: “you may draw a loafe to see if it be enough; w[i]th your knuckles; if it found & be hard; draw the rest; if not, let them stand a while longer; experience is soone learned; but if you leave the bread too long; it will make it red within, & of ill [relish].”

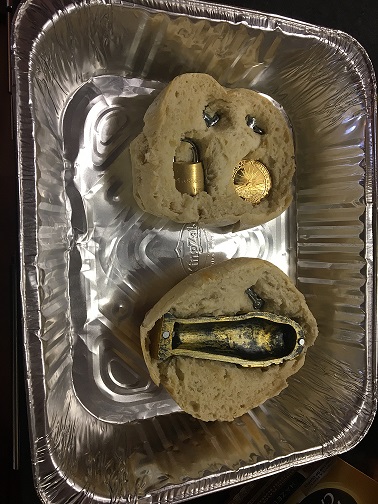

At 12:35 pm, I removed the three bread loaves from the oven, halved two of them, and proceeded to jam objects into the halved loaves. I let them air dry until the next evening. I did exert considerable pressure on the objects once lodged into the mush of the bread (the correct term escapes me), which the images will illustrate.

10.02.17

Bread casting in beeswax and sulfur. The first set of molds were done in beeswax, and the next set in sulfur.

Casting in beeswax

Ingredients:

Beads of beeswax

Apparatus:

Hotplate

Tin can

The hotplate was plugged in and the dial was turned to ‘2.5’, to heat. I filled the tin can with 35 mL of beeswax, and placed it atop of the hotplate. The wax began to liquefy, rather slowly, so the dial was raised to 3. At which point, the melting process accelerated. I continued to stir the wax with a chopstick. Once the wax had completely melted, I poured the melted wax into one set of bread molds, filled each mold to the top, and let it sit for a little over an hour. I returned to the lab around 1:30 pm, at which point the wax casts were ready for removal. However, the wax casts were lodged so deeply and firmly in the bread that I was forced to cut the wax molds, with a knife, and then use carving tools to chip at the dried-up bread. I worked at this process for nearly 30 min, at which point, on Tianna’s suggestion, I filled a tin can with water and dumped the bread covered wax casts into it, to allow for the bread to soak overnight. I returned to the lab the next day, 10.03.17, at 4:10 pm, and removed the remaining bread mush coating the wax molds. Of the three wax casts I set, two came out in a recognizable shape, that is resembling the objects they were intended to imitate, the lock and the shoe. The coin cast was not only broken on extraction on 10.02.17, but none of the details were visible.

Casting in sulfur

Ingredients:

Sulfur powder

Linseed oil

Apparatus:

Beaker

Tin can

I primed the bread molds with Linseed oil to allow for easy removal of completed casts from the bread moulds. In retrospect, a decision I am grateful to have made as the removal of beeswax casts was laborious and timely. Sadly, my sulfur casts came out broken, an outcome I did not foresee and was rather disappointed by.

I poured some sulfur powder into a beaker, and set it on a hotplate, at 11:27 am, the dial was turned to 1. I began to stir the mixture, which felt like slightly wetted sand, dense but still fine, and easy to move. I stopped mixing for a few seconds to observe the effects of heat on unmixed sulfur, at which point I noticed streams of liquified sulfur running through dry portions of the sulfur powder. At 11:30 am, I turned the hotplate dial to ‘1.5’, to speed up the melting process. Still stirring the sulfur, I felt it clump up. At 11:33 am, it began to melt. At 11:39 am, the hotplate dial was turned to ‘2’. At 11:45 am the sulfur had melted, at which time I removed the beaker from the hotplate, and poured the liquified sulfur into the bread molds.

I returned the following day, 10.03.17, to extract the sulfur casts, and found the process easy, thanks to the linseed oil. As it turned out, I did not melt enough sulfur, so the molds were not filled to the top, as they had at the earlier casting session with beeswax. Additionally, the set of bread molds used for the sulfur casting were not as deep, and had more fine and intricate details. This was likely the cause of the failure to produce any decent sulfur casts. On extraction, all were broken. Although the casts did not come out whole, I was pleasantly surprised by the level of detail the sulfur casting method produced. The arches were plainly visible. I don’t think this level of detail would have been possible with beeswax.