Table of Contents

PHS: PRIMARY SOURCES--USE CONTEMPORANEOUS ONES. SEE EMILY FOYER, SOPHIE PITMAN, AND ROBIN REICH ANNOTATIONS FOR SOME POSSIBLE ONES. ALSO, REMEMBER THAT THE MS. INCLUDES REF TO MATTHIOLI, DODOENS, OTHERS?

Preliminary Plan

Preliminary Annotation Plan #2 for Flower Preservation in Ms. Fr. 6401. Participants:

Ana Matisse and Caitlyn Sellar

Larger "preservative" context, e.g., plague recipe (vinegar; preservative, 170v); WORD FOR SAND IN THIS RECIPE: arene? Sable? meaning of "studies"

connection to still life, decorating when flowers are out of season; mentioned in 1670s Gerard de Lairesse

Look at folio images--is this a work of experience?

Flower sourcing: Union square

New York Botanical Gardens, Vanessa Sellars, Director of the Humanities Institute, excellent library

2. Recipe: p120v_5

<head>Keeping dried flowers in good condition year round</head><ab>

<m>River sand</m>, that is washed by the current of water, is good when strained in a cloth to make the powder compact.</ab>

<ab>This is a rare secret, and which is pleasing for decorating tables, rooms, studies out of season when winter denies you flowers. Be advised to pick them when they are in full vigor and still growing, because if you take them when no longer in bloom or when they are starting to wilt, they will not keep. Having therefore chosen them, take some <m>sand</m>, the leanest and driest you can find, that must be very well ground, like the one <pro>goldsmiths</pro> use to sand <m>enamel</m>, or like the one [used] for engraving. But this <m>sand</m> must not be dusty at all, nor must it stay on your hand or leave a trace when you have ground or poured it, because it is[f]

Make sure your box is well sealed so that the <m>sand</m> does not get out. Keep it uncovered in sunlight and keep it away from the evening dew, and the moisture of the night, and cover it and keep it in a dry place.

You can not put these aforementioned flowers in big vases, because if you want to take one out, you will take the whole bunch with it.

Be advised to not pick your flowers when it is rainy or humid, but when the sun has been shining on them.

Flowers can also be kept just as beautifully in <m>vinegar</m>, distilled in a vase, well-sealed so it there is no draft, well-sealed with <m>wax</m> and <m>mastic</m>. [For] carnations and roses, the residue of <m>vinegar</m> usually makes them rot. If the <m>sand</m> is dusty, and sticks to the flowers so that it hardly comes off with a brush, it is no good. The leannest <m>sand</m> is the best.</ab>

<cont/> p0120v_4

a sign that there is some humidity and if the flower was also watery it would rot. Moreover the sand must not be <del/> rough because its weight would make the flower lose its original shape. Once you have chosen it accordingly, take a <tl>box</tl> in which you first make a layer of sand on which you will display the stalk of the flower laid in a way that the flower does not touch nor the bottom nor the edges of the <tl>box</tl> and stands in the air. Then add more <del/> sand on the stalk so that it remains strong and solid. Finally take some of the same sand and sprinkle and subtly display it with two <tl><bp>fingers</bp></tl> on the flower like the flow of an <ms> <tl>hourglass</tl></ms>. And once the flower is <del/> covered, strike with your <bp><tl>fist</tl></bp> the table on which the <tl>box</tl> is displayed, so that the sand lowers and surrounds everything. Finally cover the entire flower, and lay other flowers, one after the other, as many as the <tl>box</tl> can hold. Then put the <tl>box</tl> in <tmp>warm sun</tmp> for <ms><tmp>several days</tmp></ms>. And as the flower dries, the sand that goes with it continues to press and prevents it from rotting and tightening and consequently, it dries and keeps its original shape. And to do so, make sure to chose boufarcis, <pa>marigold</pa>s, the <pa>yellow meadow's flowers</pa> called <la><pa>rammenlus</pa></la> or <la><pa>palta lupina</pa></la>, <pa>amaranth</pa>, and similar flowers like <pa>broom</pa> and others which you will know from experience.

The sand the <pro>goldsmith</pro>s use to sand <m>enamel</m>s and the white one which the <pro>glassworker</pro>s use and any type of fine sand which does not have much body, put it through a <tl>sieve</tl> made of <m>horsehair</m> because this matter must not be very thin. Then dry it well in the <env>sun</env> for <ms> <tmp>several days</tmp></ms> in order to remove the dampness and ventilate it as you would do with <m>wheat</m> so that the dust goes away. Once cleaned of dust and dried, use it as you know.

<pa>Pansies</pa> can be preserved in the same way.</ab> </div>

3. Plan:

- Historical: We will research the history of the study of flowers in herbals and other herbaria in Early Modern France. This recipe is stated to specifically be for decorating as well as for the study of flowers year-round-- Why might it have been better to dry the flowers for examination rather than press them into the book (3D effect?)? Which was more common? What type of information did they get from these studies? Were these flowers models for other artificial casts of flowers? Were these flowers the ones which were put under glass cases? In what context would one want flowers for both decoration and study? This type of flower drying is still in use, and has been documented at different points throughout the centuries: The New England Farmer, Volume 10 by Thomas Greene Fessenden (1832); http://www.finegardening.com/drying-flowers-sand

- Object Based: It might be hard to find such preserved flowers in museum objects, but it might be possible to find them in paintings. Perhaps we can contact Alix Cooper to talk with her about her research as well. There are certainly a number of herbals and herbaria that we would be able to take a look at as well.

- Hands-on: We will dry flowers using the recipe (there are two experiments included in the recipe)

4. Materials:

- Box -- what type of box would have been used? Probably wooden, which can be purchased from a craft store

- Sand-- fine grain sand, like the kinds available from craft stores-- I am not sure how we would strain it using something approximating horse hair: "Having therefore chosen them, take some <m>sand</m>, the leanest and driest you can find, that must be very well ground, like the one <pro>goldsmiths</pro> use to sand <m>enamel</m>, or like the one [used] for engraving. But this <m>sand</m> must not be dusty at all, nor must it stay on your hand or leave a trace when you have ground or poured it, because it is The sand the <pro>goldsmith</pro>s use to sand <m>enamel</m>s and the white one which the <pro>glassworker</pro>s use and any type of fine sand which does not have much body, put it through a <tl>sieve</tl> made of <m>horsehair</m> because this matter must not be very thin.

<m>River sand</m>, that is washed by the current of water, is good when strained in a cloth to make the powder compact.</ab>

If the <m>sand</m> is dusty, and sticks to the flowers so that it hardly comes off with a brush, it is no good. The leannest <m>sand</m> is the best.</ab>" - Flowers-- Pansies, marigold, lupines, etc. are mentioned specifically in the text. There are a number of flower shops/nurseries that would sell such flowers

---- if we decide to do both experiments included in the recipe: - Vinegar-- Should be organic and “of the mother”, but it is not specified what type of vinegar is needed (much like our verdigris experiments)

- Flowers can also be kept just as beautifully in <m>vinegar</m>, distilled in a vase, well-sealed so it there is no draft, well-sealed with <m>wax</m> and <m>mastic</m>.

- Wax-- can be bought from a craft store; we would need to do some research on types of wax available in 16th century France

- Mastin-- a type of plant resin ; should be available in plant shops, but we would need to do some research to see if it is the same type used in the past (would this matter since it is just a part of the seal??)

- Vase -- made of glass, can be bought in a craft store, flower store, etc.

5. Bibliography:

Secondary Sources-

Picturing the book of nature : image, text, and argument in sixteenth-century human anatomy and medical botany by Sachiko Kusukawa

“Still Life sources” in Still Life Paintings- Technique and Style by Arie Wallert

“Inside the Box : John Bartram and the Science and Commerce of the Transatlantic Plant Trade” by Joel T. Fry in Ways of making and knowing : the material culture of empirical knowledge edited by Pamela H. Smith, Amy R. W. Meyers, and Harold J. Cook

Cultivated Power: Flowers, Culture, and Politics in the Reign of Louis XIV by Elizabeth Hyde

The Wild and the Sown: Botany and Agriculture in Western Europe, 1350-1850 by Mauro Ambrosoli

History of Botany (1530 – 1860) by Julius Von Sachs (from 1906)

“Dominion, demonstration, and domination : religious doctrine, territorial politics, and French plant collection” by Chandra Mukerji in Colonial botany : science, commerce, and politics in the early modern world edited by Londa Schiebinger and Claudia Swan.

The Science of Describing : Natural History in Renaissance Europe by Brian Ogilvie - the bibliography section of this book also lists a number of herbals and herbaria to check out

”The Nature of Nature in Early Modern Europe” by Daston, Lorraine in Configurations 6 (1998)

Orientalism in early modern France : Eurasian trade, exoticism, and the Ancien Régime by Ina Baghdiantz McCabe

Primary Sources-

The Herball, or, Generall historie of plantes /gathered by John Gerarde of London, master in chirurgerie by Gerard, John (1597) - http://www.botanicus.org/page/1956117

De simplicibus medicamentis ex Occidentali India delatis, quorum in medicina usus est by Nicolás Monardes (1574) - http://gateway.proquest.com.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&res_dat=xri:eurobo-us:&rft_dat=xri:eurobo:rec:hin-wel-all-00002450-001

Herbarium / Oth. Brvnfelsii ; tomis tribvs exacto tandem studio, opera & ingenio, candidatis medicinae simplicis absolutum. Quorum contenta, index cuiusquam tomorum suo loco explicat (possibly by Weiditz, Hans, d. ca. 1536) - http://gateway.proquest.com.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&res_dat=xri:eurobo-us:&rft_dat=xri:eurobo:rec:hin-wel-all-00000055-001

L’histoire des plantes, traduicte de Latin en François avec leurs pourtraicts, noms, qualitéz & lieux où elles croissent by Geoffroy Linocier (1620) - http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1041793n

Edited/revised notes:

Materials

- Box — I have identified several wooden boxes that can be purchased cheaply and are sealed on the edges to hold the sand in — the box does not need a top — because the focus is on the sand and the flower within the box, I’m not sure the type of wood used to make the box was of concern to the a-p

- Sand— The word for sand in the recipe is “sable”; the sand should not be too powdery, too wet, or too thin, and should be “lean”— the a-p mentions that it should not “stay on your hand” which actually gives a good idea as to how fine the sand should be

- Flowers-- Pansies, marigold, lupines, etc. are mentioned specifically in the text — most of these flowers are out of season, but there are still a number of organic flowers available in the Union Square market that could be used— the a-p specifically warns against roses and carnations in the vinegar experiment, so I will try to avoid using those in either experiement. I think I would like to try preserving the same type of flower for both experiment 1 and 2 in order to compare them

- Vinegar-- the recipe specifies a distilled vinegar, and it should probably be organic as well— the only distilled vinegar I know is white vinegar

- Wax & mastin — these are used as a part of the seal on the vase in order to cover the vase— I am thinking of approximating with plastic wrap for the seal, since I think the focus of this experiment is on the vinegar and the flower

- Vase — can be purchased cheaply from a flower shop or craft store

Procedure

EXPERIMENT 1:

- Having therefore chosen them [flowers], take some <m>sand</m>, the leanest and driest you can find, that must be very well ground, like the one <pro>goldsmiths</pro> use to sand <m>enamel</m>, or like the one [used] for engraving. But this <m>sand</m> must not be dusty at all, nor must it stay on your hand or leave a trace when you have ground or poured it, because it is[f] a sign that there is some humidity and if the flower was also watery it would rot. Moreover the sand must not be <del/> rough because its weight would make the flower lose its original shape. Once you have chosen it accordingly, take a <tl>box</tl> in which you first make a layer of sand on which you will display the stalk of the flower laid in a way that the flower does not touch nor the bottom nor the edges of the <tl>box</tl> and stands in the air.

— The flowers should be laid out in a box, with a layer of sand on the bottom so that the flower does not touch the bottom at all— it seems the flower should be standing in the box (should it be standing with the stem in the sand or the flower itself provides the base?- based on the next step, it should be the stalk) - Then add more <del/> sand on the stalk so that it remains strong and solid.

— adding more sand around the base so that the flower does not fall over - Finally take some of the same sand and sprinkle and subtly display it with two <tl><bp>fingers</bp></tl> on the flower like the flow of an <ms> <tl>hourglass</tl></ms>.

—sprinkle some sand over the flower — presumably to get sand to surround the flower without crushing it - And once the flower is <del/> covered, strike with your <bp><tl>fist</tl></bp> the table on which the <tl>box</tl> is displayed, so that the sand lowers and surrounds everything.

— this step is probably to even out the sand in the box - Finally cover the entire flower, and lay other flowers, one after the other, as many as the <tl>box</tl> can hold. Then put the <tl>box</tl> in <tmp>warm sun</tmp> for <ms><tmp>several days</tmp></ms>. And as the flower dries, the sand that goes with it continues to press and prevents it from rotting and tightening and consequently, it dries and keeps its original shape

— this step indicates adding other flowers to the box, which would be difficult if it was filled with sand already. likely, the author-practitioner would have needed to lay out other flowers next to the first one before filling the box with the rest of the sand - Make sure your box is well sealed so that the <m>sand</m> does not get out. Keep it uncovered in sunlight and keep it away from the evening dew, and the moisture of the night, and cover it and keep it in a dry place.

— the a-p indicates sealing the box but then says to keep it uncovered— he is likely referring to keeping the bottom and sides sealed to prevent the sand from getting out, but keeping the top open to the sunlight — based on his descriptions of the evening dew, it probably needs to be placed in a warm, dry place, but not necessarily a well-lit one - You can not put these aforementioned flowers in big vases, because if you want to take one out, you will take the whole bunch with it.

— refers to the difficulty of using the flowers for decoration in a home — possibly because the petals get dry and are not easily maneuverable?

EXPERIMENT 2:

- Flowers can also be kept just as beautifully in <m>vinegar</m>, distilled in a vase,

-- placing the flowers in a vase filled with vinegar-- presumably the flowers will float, so I will have to figure out a way to keep it submerged - well-sealed so it there is no draft, well-sealed with <m>wax</m> and <m>mastic</m>.

— the vase the flowers are placed in needs to be sealed well— because I am focusing on the use of vinegar to preserve the flowers, I will probably use plastic wrap or something similar to seal the top of the vase, especially considering the recipe does not say what will be sealing the vase (what would the wax have been sealing on the top to keep it covered? is it a piece of glass, wood, etc.?)

— it wouldn’t dry them out in the same way as the first experiment, so could this second experiment change the look of the flowers? would the flowers preserved in this way be used for something different (i.e. the study of flowers for paintings vs the study of flowers for science?)

Further research plans:

- Since our last discussion, I made an appointment with the New York Botanical Gardens library which I was unable to keep due to illness-- I will make another appointment in the coming week to look at some of their collection of herbals, herbaria, and possibly woodblocks as well

- In my historical research, I am still interested in examining the place of this type of preservation of flowers in the history of natural science and the writing/drawing of scientific literature in Early Modern France. I have been reading Brian Ogilvie's The Science of Describing, which has been extremely helpful so far, along with Kusukawa's Picturing the Book of Nature

- Because I am unsure of whether these preserved flowers were used for natural history study or still-life art study, I will probably also explore some still life paintings of flowers that feature varieties which do not generally bloom at the same time

- This recipe does not describe "preserving" or "drying" specifically in the title-- only "keeping" the flowers; however the second experiment uses vinegar to keep the flowers, which was used in a number of other medicinal recipes in the manuscript, including one about "preserving oneself":

<id>p170v_a3</id> <head>To preserve oneself</head>

<ab><m>Acetum</m> paratum ex <m>ruta</m> <m>baccis juniperi</m> simul tusis Eo<lb/><m>aceto</m> extinguantur <m>lateres</m> igniti. Et vapor excipiatur ore [&]<lb/>naribus. <m>Rue</m> <m>vinegar</m> together with crushed <m>juniper berries</m>. Pour the <m>vinegar</m> over red hot <m>bricks</m> and inhale the vapor through the mouth and nostrils. This is to preserve oneself when going into noxious air: a garment can be perfumed with this vapor in order to remove infection from a room, house, etc. And if you find yourself in a place where you do not have this preparation, carry <m>rue</m> and <m>berries</m>[e] crushed together, then, if need be, boil them in <m>vinegar</m> and use as described.</ab>

What are the implications of the word "keep" vs. preserving or drying? - I also have a number of books on the historical distribution of plant species in Europe, especially since the cultural meaning of flowers likely changed as new types of flowers travelled between European and Asian lands -- because the author-practitioner mentions specifically using these preserved/dried flowers as decoration, it would be beneficial to understand such cultural meanings, of which Elizabeth Hyde's Cultivated Power has considered

11/27/16 UPDATE

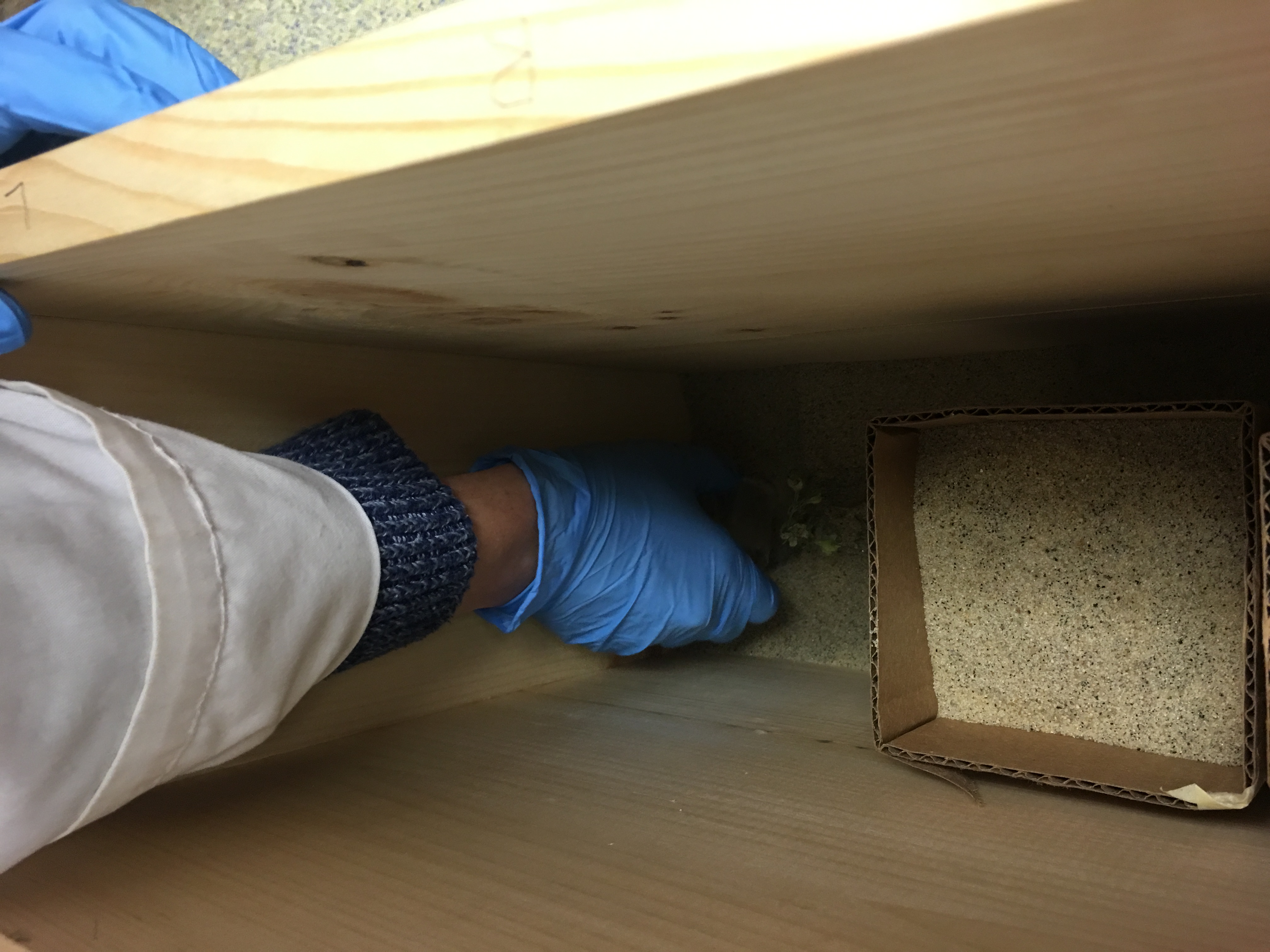

Experiment procedures:Sand Trial 1 - Beach sand

Use three-to-four flowers, as close to those mentioned in the manuscript recipe as possible

- Take sand and spread a thin layer on a sheet/plate/etc. and place in the fume hood to dry overnight (layer should not be too thin)

- If needed, pour sand through sieve to remove rocks, seashells, etc.

- Prepare the flowers (possibly remove the leaves from the flowers?)— cut stems to required length, measure blooms and stems

- Set up the box with a layer of sand on the bottom, and set up three-to-four flowers along the bottom standing upright (use the sand to ensure they are standing in the air)

- Add more sand to the box, slowly, layering the sand up in the box and making sure that the flowers stay standing (this step will likely require two people)

- Carefully sprinkle/spread the sand around the petals of the flower, being careful not to crush the flower

- While layering the sand, strike fist on the table as needed to even out the sand

- Once the flowers are covered completely, put the box in a (warm?) dry place, leaving the box itself uncovered

- Leave the flowers in the box for one and a half to two weeks (based on modern day recipes; this information is not included in the manuscript)

- The recipe does not state how to remove the flowers, but: tip the box so that the sand falls out of one corner, holding the flowers at the bottom of the stem until the sand has been poured out from the box to remove the flowers

- After the flowers have been removed, use a brush to remove sand from the petals and stem as needed

Sand Trial 2 - Kremer sand (similar to goldsmith’s sand)

(steps same as above)

Sand Trial 3 - commercial sand

(steps same as above)

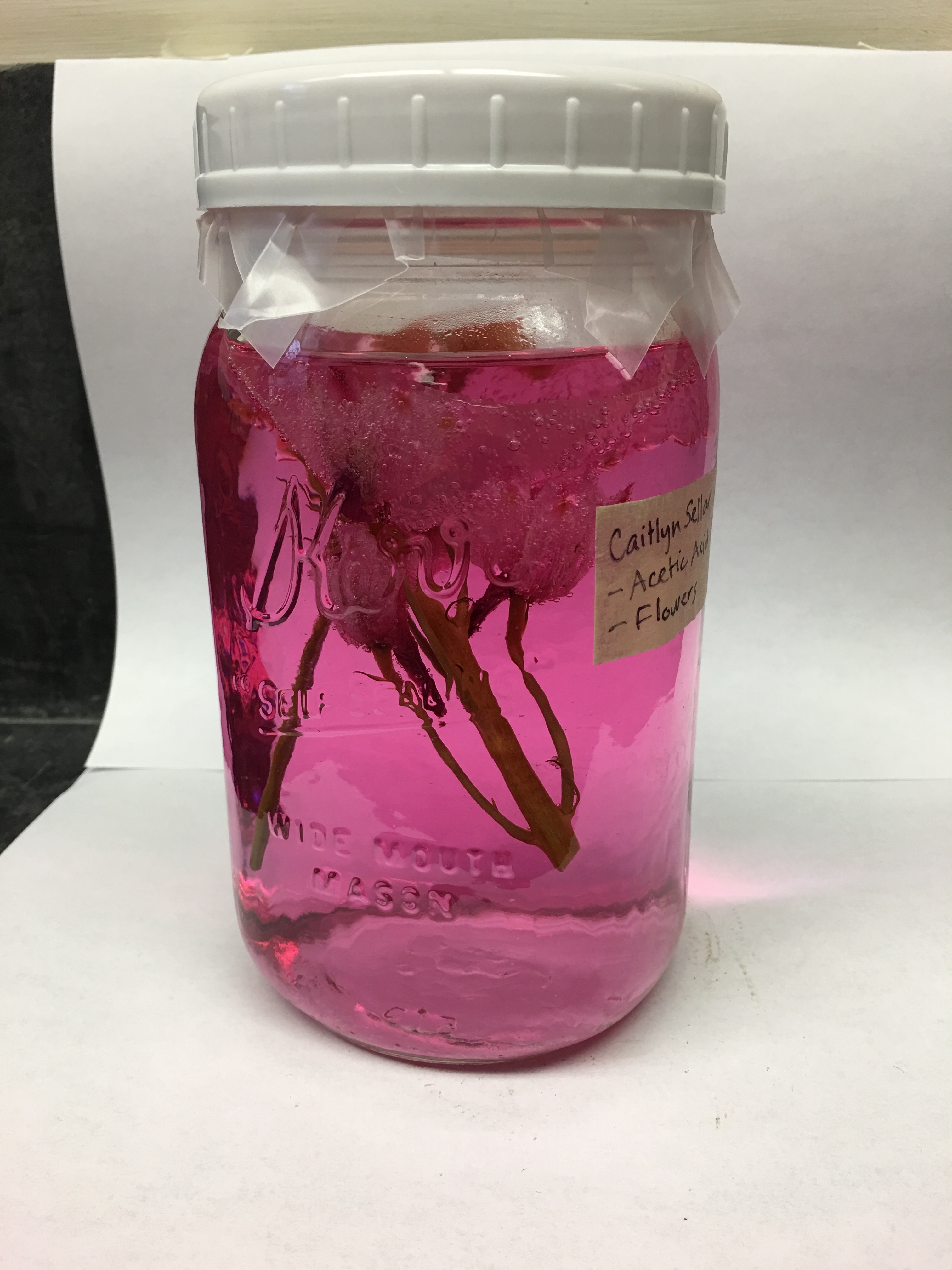

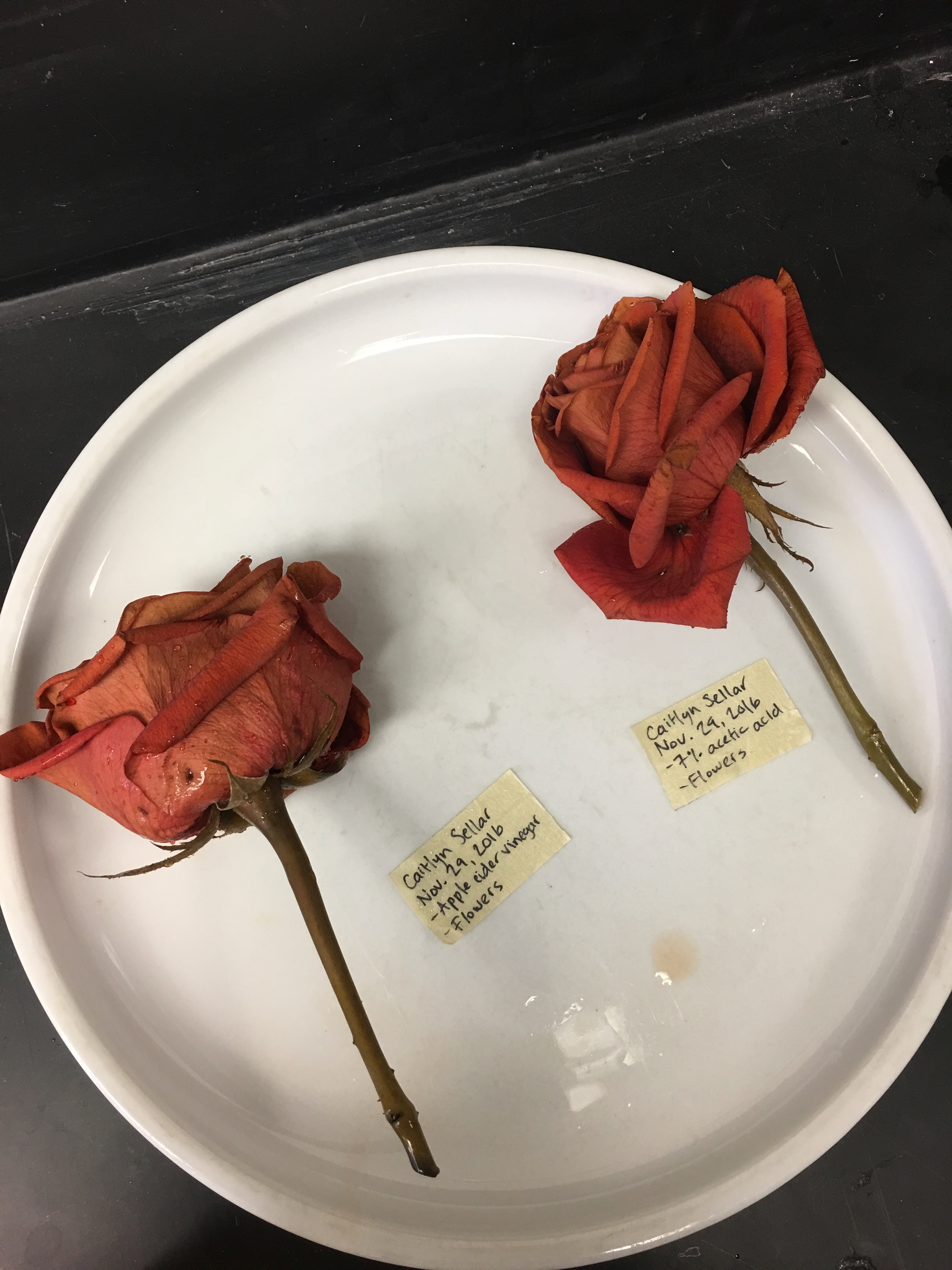

Vinegar Trial 1 - Half-filled vase (50% glacial acetic acid)

Use three flowers, same as those used in sand trial

- Distill glacial acetic acid with water to create 50% acid concentration (Documents_MSDSVendors_2016_November_29_02-15-12-879_AM.pdf)

- place cut flower (delphinium and larkspur) in mason jar with vinegar — the flowers should be cut shorter than the vase

- place cut rose in mason jar with vinegar in the same way

- cover the jars with saran wrap to seal the top of the vase/jar

- leave flower in jar and check periodically to see how flower is faring

Vinegar Trial 2 - Submerged in vinegar (50% glacial acetic acid)

Use three flowers, same as those used in sand trial

- Distill glacial acetic acid with water to create 50% acid concentration

- place cut flower (delphinium and larkspur) in mason jar and fill with vinegar so that the flower is submerged

- place cut rose in mason jar with vinegar in the same way

- cover the vase/bottle with saran wrap to seal the top of the vase/jar

- leave the flower in vase/jar and check periodically

Vinegar Trial 3 - Half-filed vase (7% glacial acetic acid)

(Steps same as vinegar trial 1)

Vinegar Trial 4 - Submerged in vinegar (7% glacial acetic acid)

(Steps same as vinegar trial 2)

Vinegar trial 5 - Half-filled vase (5% apple cider vinegar)

(Steps same as vinegar trial 1)

Vinegar trial 6 - submerged in vinegar (5% apple cider vinegar)

(Steps same as vinegar trial 2)

Projected timeline:

11/27 - dry sand

11/28 - supplies gathered and set up vinegar trials (try to check every couple of days to record condition) ; make marks on inside of boxes at cm marks

11/29 or 11/30 - set up sand trial 1

11/30 or 12/1 - set up sand trials 2 and 3

12/12 - remove sand from trials

Materials

- Flowers —roses, delphiniums, larkspur (9 of each)

- Sand — commercial sand from lab, beach sand from Jersey Shore, Kremer sand

- Boxes (built at home)

- Mason jars from lab

- Vinegar — apple cider vinegar

- Scissors

- Tongs (maybe)

- String (maybe)

- Rubber bands

- Masking tape

- Glue

- Fume hood

- sieve

- distilled water

- glacial acetic acid from lab

- brushes

I have now collected my flowers and beach sand and also made my wooden boxes. Over the break I also continued my research into how vinegar is made (so as to determine the acetic acid concentration needed in the experiment), the cultural meanings of flowers in France, how flowers were used in decoration in Early Modern France, and worked on gathering more information about the flowers mentioned in the MS from the herbals I looked at in the New York Botanical Garden library on Tuesday. Most of the herbals were French translations of other books, but there were a few herbals which were helpful in learning about the properties/names/locations/etc. of the plants from the recipe, including Matthioli and Dodoens (mentioned in the Ms). The librarian at the archive was also unsure of 'boufarcis' in the list of flowers, and this is the only flower which I have not been able to find information on (including searching variations in spelling). I spoke with Vanessa Sellers at the library as well, and may try to contact her to see if she has any ideas.

I have also continued to look at the context of the recipe/materials in the manuscript: how flowers/sand/vinegar are used in other recipes, other types of preservation, and if there are any other recipes where the purpose of the created objects, etc. was for ornamental use. After my experiments are completed, I would like to see if the flowers still hold their smell and how vibrant their color is in addition to seeing if they actually hold their form-- I have found a book on the history of the senses (on request at the library) that I hope will have some relevant information on smell and color during the Early Modern period; considering smell was important in medicine as well as the information I have found on the use of dried flowers to provide a type of perfume (potpourri) later on in the seventeenth century, I would be interested to see if the flowers could have played a role in creating a sweeter or more pleasant smell in homes even after they were dried. I am also interested in seeing how well they hold their color, and how closely they resemble the live flowers

11/24/16 2PM

Kremer’s

- purchased quartz powder, 0.04-0.15 mm

- http://shop.kremerpigments.com/media/pdf/58630_SHD_ENG.pdf

11/25/16 5PM

Sandy Hook

- sand gathered from the beach, close to the edge of the water (but where it was still 'dry')

- gathered roughly 35-40lbs of beach sand

- sand contained pieces of sea shells, rocks, etc., but we took out the cigarettes, etc. if we saw them as we were putting them into bags

11/26/16 12PM

Hillsborough B&T Florist

- purchased three types of flowers: roses, delphiniums, larkspur

- roses are specifically mentioned in the manuscript in the vinegar recipe, but not in the sand recipe — I wanted to use the same types of flowers for all experiments to see how they are different, so I will use roses for both sand and vinegar

- delphiniums are in the same family as ranunculus and have similar blooms

- larkspur (Consolida regalis) have small blooms— most of the flowers listed in the manuscript have small blooms and this flower is native to France (also from the ranunculus family, and described as a buttercup in a number of botany books), it is grown as an ornamental plant, and

11/26/16 1PM

Parents' house, NJ

- measured the flowers to see how long the blooms and stems were to make sure that they would fit into the box (height-wise)

- used pine wood from Lowe’s, Elmer’s Interior Carpenter’s wood glue, finishing nails, saw

- 16” wide, 6” depth, 18.5” tall boxes (measured from outside)

- will need to measure the inside of the boxes to ensure that we can record how many cubic cm of sand was used in each trial

Vinegar research

- French Orleans method used from 15th century on- yields 7% acetic acid content in modern day, but could not yield anything less than 5% at any point ; developed in 1394 century by vinegar guild in Orleans

- Most descriptions I have found of distilled vinegar describe it as pure acid with water and none of the other ingredients that are added to vinegar used for consumption (Mortimer) - this is in line with what Hupkes M. found in her annotation on distillation in the MS -- I have placed two requests for books on general distillation at the library and hope to get them by the middle of the week

- In choosing acetic acid concentrations for my vinegar trials (excepting apple cider vinegar, which I am using because it was the type most commonly referred to as being used in the kitchens), I decided to go with 7% and 50%. The 7% number was chosen based on the information I have been able to gather about the Orleans method of creating vinegar in Early Modern France. In books of the time, the acid concentration is not mentioned when describing this process (that I have yet found), but vinegar makers who still use this method have reported 7% acetic acid concentration in their resulting product. I chose 50% as my second number based on references to distilled vinegar elsewhere in the manuscript which describe it as being used to carve into materials (amber, wood, etc.); I thought that it should be a fairly high concentration if it was being used to carve, but that it should not be too high as to 'eat away' at the plants themselves, which are an organic material

Information about flowers from herbals

Vinegar trial check table

Name: Caitlyn Sellar, Emma Le Pouesard, Tianna Uchacz

Date and Time: Nov. 29, 2916 ; 5:00PM

Location: Making & Knowing Lab

Subject: Carrying out reconstruction experiments

Pouring Beach Sand into Box 3

- CS poured a generous layer of sand into the bottom of the box, something around 4 cm

- CS placed flowers in the box into the layer of sand, making sure the stems did not touch the bottom of the box itself

- ELP held delphinium in place

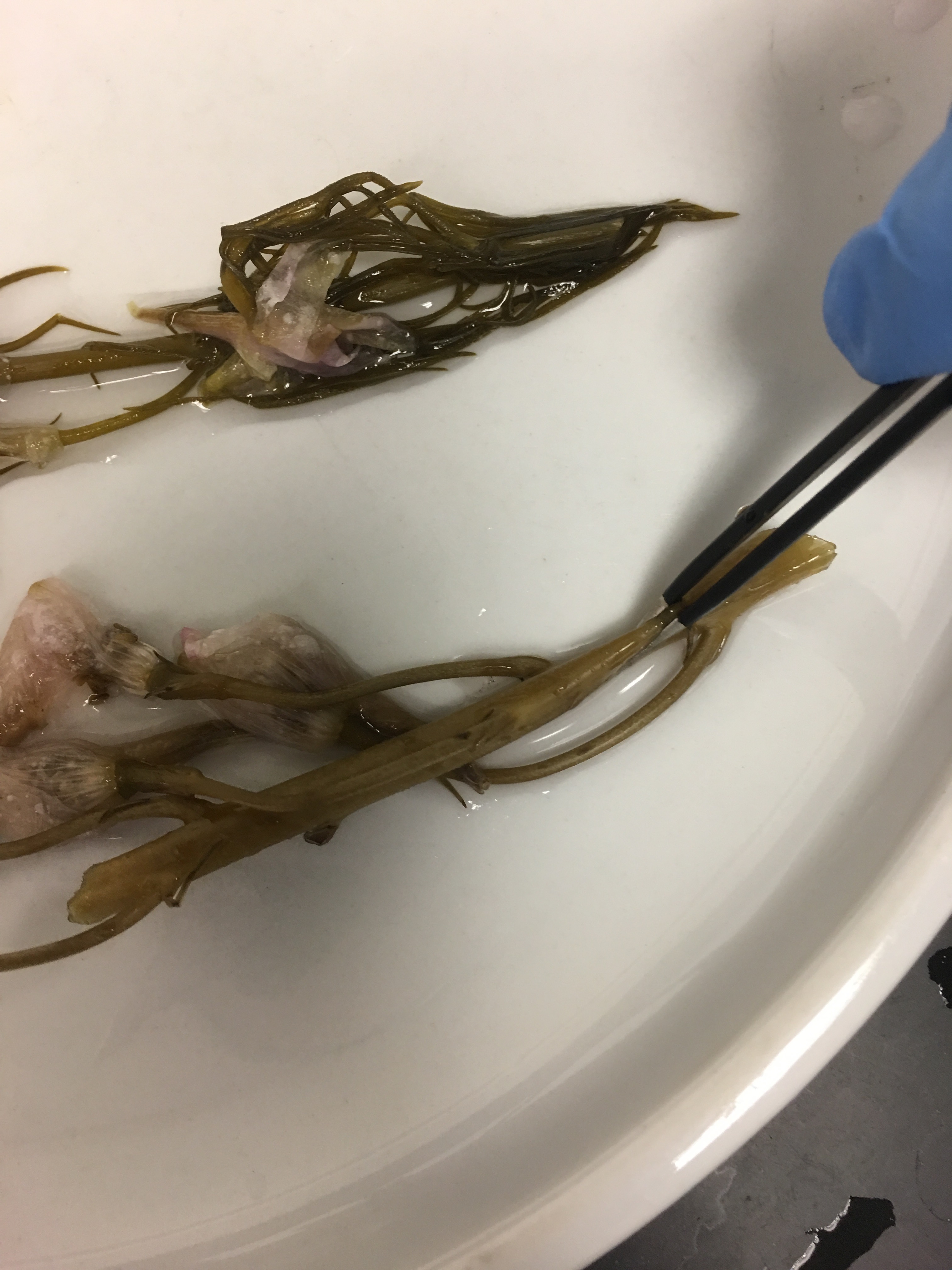

- TU tried to keep larkspur erect with chopsticks

- the rose stood up well on its own

- CS remarked that the rose's ability to stand might relate to the list of flowers the AP gave in the recipe, all of which seemed sturdy of stalk

- smaller beaker works better for pouring sand around the flowers

- ELP noted, surprised, how well the delphinium was holding up in the sand, given how easily the blooms were falling away with handling earlier

- It became apparent that we did not have enough beach sand

- ELP came up with solution of building tiny cardboard boxes to put around the tops of the flowers to hold what little sand remained.

- CS began pouring with two hands cupping the beaker after she noted that it gave her more control over how slowly she poured

- ELP mused that pouring sand is like watching time pass in an hourglass

- CS developed a technique to avoid pouring directly on the flowers that entailed pouring against the wall

- TU noticed that the leaves of the rose for box 1 helped it stand up, as the rose for box 2 has no leaves and struggled to stay upright on its own

- CS noticed that after pounding the table the box was on (as the AP directed) the sand seemed to settle less—perhaps because the grains of sand were much finer

- CS observes that it is much more difficult to make the flowers stand up in the fine quartz powder than it had been in the sands

- the powder/dust kicking up from the pour was fine and voluminous enough to prompt us to get masks

- CS observed that it was easier to pour the powder around the flower petals without having to worry about damaging them because the powder was finer than the sands

- CS noted that the quartz powder also seemed to settle less than the beach sand

10:45PM

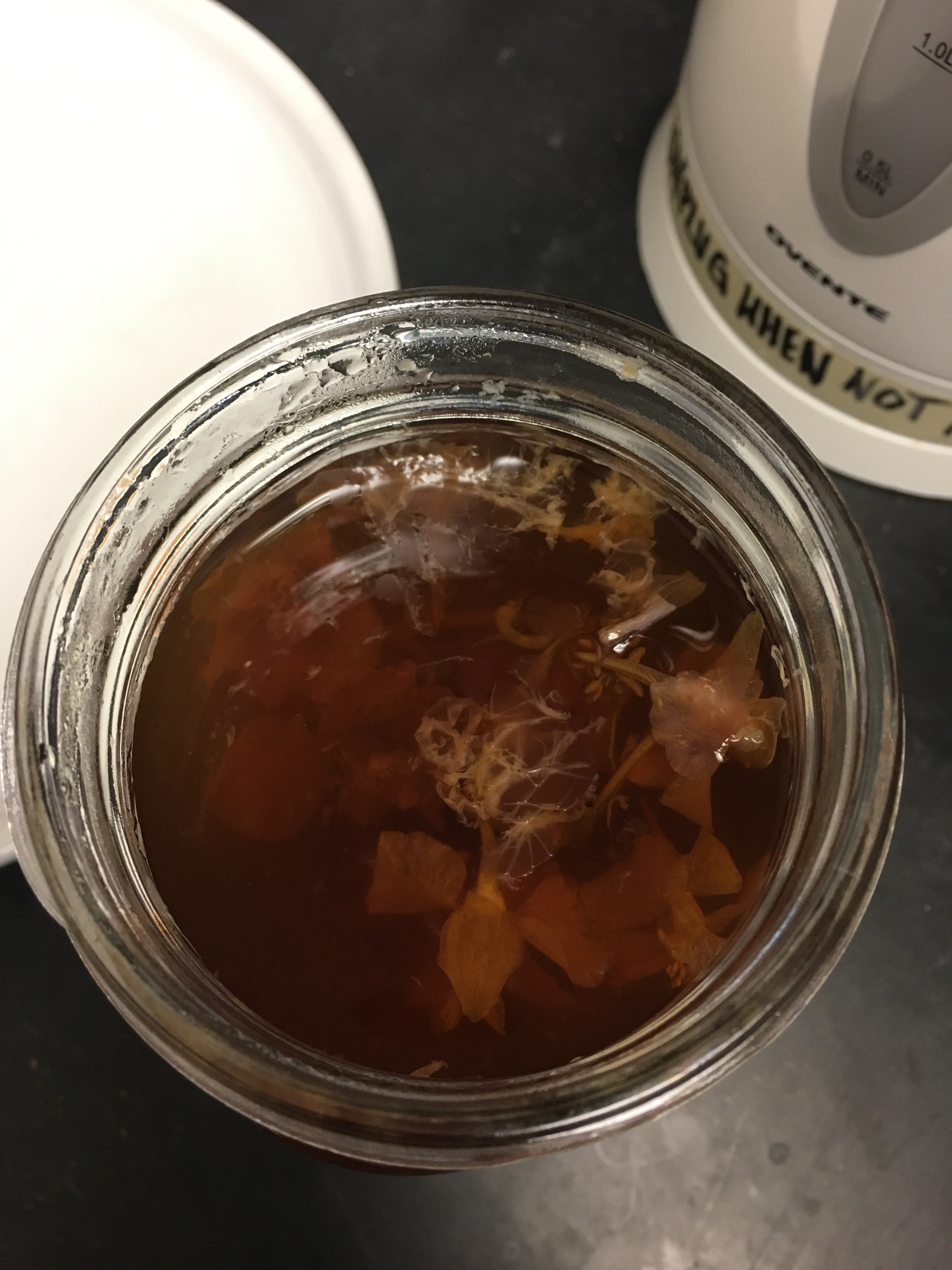

Assembling vinegar jars

- when placing the flowers into the full jars of vinegar, the flowers seemed to float so we devised a method for keeping them submerged by using a piece of circular parafilm that was larger than the lip of the jar and pushed down to the surface of the vinegar using chopsticks -- because some vinegar got on top of the parafilm which gave it some weight, the flowers underneath stayed submerged -- we had to do this for each of the jars where the flowers had to be fully submerged

- 20min after placing the delphinium in the acetic acid jars, the color of the petals began to change from purple to pink-- the larkspur in the same jars did not change color ; the "dripping" of the pigment was much more rapid in the 50% acid jar than in the 7% -- we will have to see if the fumes from the vinegar in the jars affects the rest of the petals over time

Name: Caitlyn Sellar

Date and Time: Nov. 30, 2916 ; 1:15PM

Location: Making & Knowing Lab

Subject: Checking on vinegar jars

- the pigment on the petals of the delphinium and larkspur submerged in the 50% acetic acid has turned the water pink, and both flowers seem to be disintegrating

- some of the other acetic acid jars where the delphinium petals touched the vinegar at the bottom are also slightly pink

- the d & l flowers in the apple cider vinegar do not look as "perky" as they did last night, but the flowers in the 7% acid look almost the same -- this might possibly have to do with the flowers chosen?

- it is not possible to tell how the flowers in acv (fully submerged) are faring because the vinegar is not clear, but the flowers submerged in the 7% acetic acid seem to be faring well (even the rose)

- the rose in the half-submerged acv jar still looks the same

- the stems do not seem as "stiff" as they were last night, and a number of the flowers are starting to bend

Name: Caitlyn Sellar, Emma Le Pouesard, Tianna Uchacz

Date and Time: Dec. 9, 2916 ; 4:00PM

Location: Making & Knowing Lab

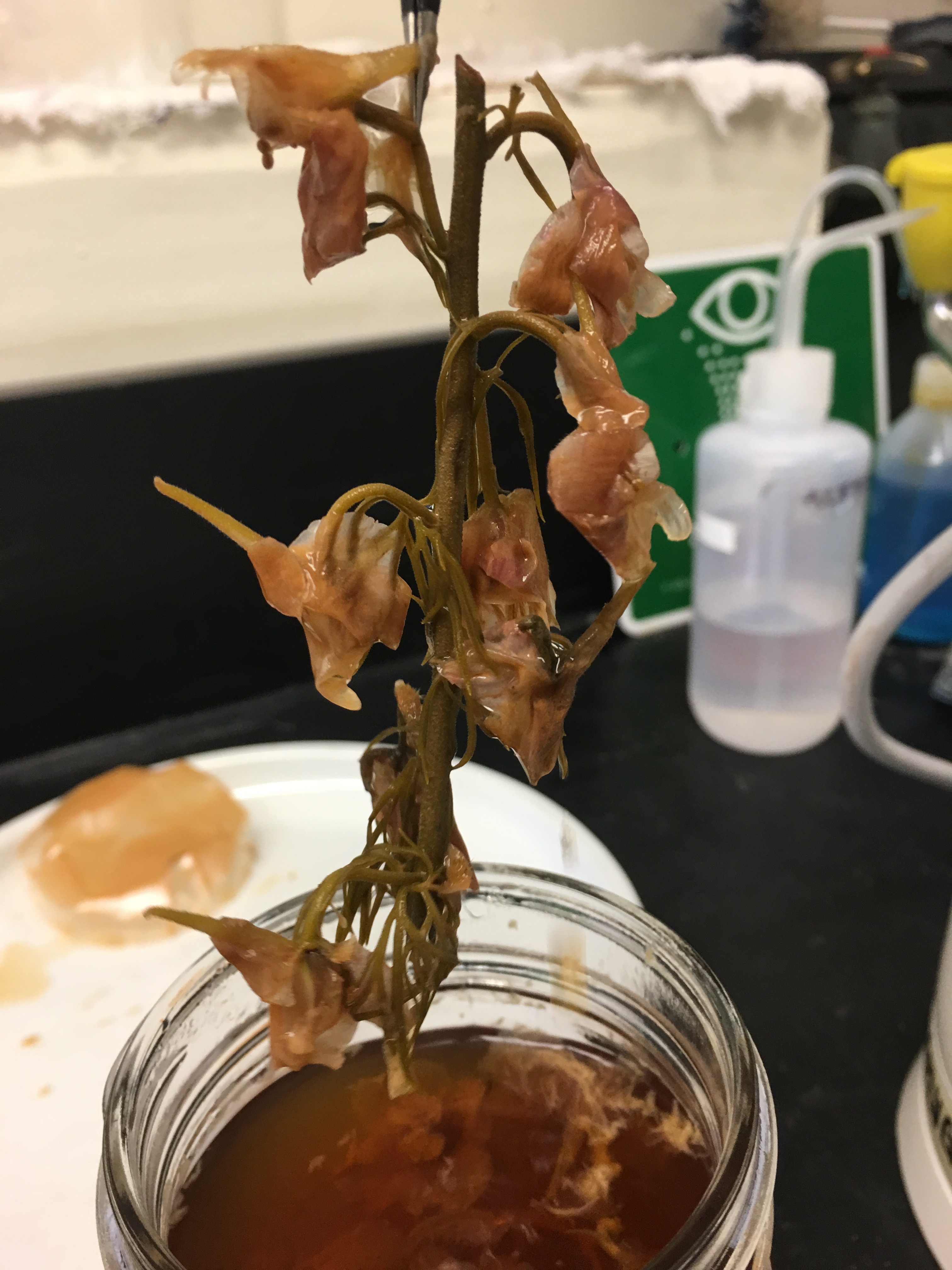

Subject: Taking flowers out of the sand in boxes

Materials:

- scooping implements and brushes (see picture)

- gloves

- goggles

- mask

- clay

- plate

- small plastic cups

- jars (3)

Procedure + notes:

- the flowers were kept in the boxes for 10 days -- this was in between the 1 and 2 week mark most modern-day florists advise-- the a-p does not denote a time for how long he wants the flowers kept in the sand, but many florists advise not to keep them in sand for too long because they can get too brittle

- we first considered tipping the boxes and pouring out the sand, because modern-day florists use this method to remove thier flowers; however, because one set of flowers had boxes fashioned around the top parts of their blooms, we decided to simply use "scooping instruments instead." -- we used a spoon, a small plastic cup, a small plastic bowl, measuring spoons, etc.

- we began by using a brush to push away some of the sand and locate where each of the flowers were in box one

- once the flowers were located, we began to dig around the flowers with the various implements-- by scooping sand out next to the flower, the sand that immediately surrounded the petals and stem fell away; this seemed like a more gentle method for removing the sand from around the flowers

- the first one removed was the larkspur from the beach sand box -- it was remarkably lifelike, and it kept most of its color

- although the flower was slightly wilting when it was put in, the blooms were still well-preserved in the condition they were put into the box; it is possible that the author-practitioner meant for people to pick flowers at their peak because then they would be preserved when they looked best (not necessarily that the preservation works better if the flowers are in full bloom and not wilting)

- the petals on the larkspurs and delphiniums felt like tissue paper-- thin, but bendable and did not break when picked up

- the roses were quite brittle, however, and small pieces broke off as these were being uncovered -- they were also the only flower to change color while being preserved, from a bright red to a deep maroon/purple -- the roses also became slightly pinched and darker brown at the point where the stem meets the flower, which was unique to this variety

- the delphiniums, although the petals themselves held up well on their own, continued to "flake" as they were uncovered from the sand in all three boxes, likely because they were wilting when placed in the boxes and the point where the petals meet the bud could have been compromised earlier

- the larkspur from the fine quartz powder box looked the best-- the petals were bright and more of the petals stayed on this than any other flower that was taken out of the boxes

- the quartz powder also stayed in place the best when uncovering the flowers- this helped to make sure that the weight of the sand did not crush the petals from the top as the bottom fell away

- we then placed the larkspur and delphinium flowers into clay "stands" to help them to stay upright, and placed the roses into jars since they were more top-heavy. we also collected the flower petals that had fallen while they were removed from the sand, and placed them into small cups

Questions:

- why did the roses change color when the delphinium and larkspur did not?

- why does it appear that the salt from the beach sand did not have an effect on the preservation process?

- why did the rose stems become thin at the top, where the stem meets the flower, when this did not happen to the others?

Vinegar trial check-in:

- there was little change in the flowers since the last check-in, although it seems that the larkspur in the apple cider vinegar is holding up better than some of the others

- it is surprising how well the roses are doing in all of the vinegar-- they were not meant to preserve well using vinegar, but they are doing better than a number of other blooms in the vinegar trials

- it does seem that the vinegar is condensing into droplets on the petals and could be affecting how well they hold up

- Question: why are the roses doing so well?

Question: what will happen when the flowers are taken out of the jars? - if i were to do this experiment again, I would add a control jar of water to test against the vinegar, and also possible add a time variable as well for when they are taken out ; it is possible to see the changes in the flowers through the jars, but we do not know if there would be any changes once they are taken out

it is also a possibility that he meant for the flowers to be sealed around the stem, and not above the bloom -- the vinegar condensing on the petals could affect the way they are preserved

Name: Caitlyn Sellar, Emma Le Pouesard, Tianna Uchacz

Date and Time: Dec. 19, 2916 ; 1:30PM

Location: Making & Knowing Lab

Subject: Sorting vinegar jars and removing some flowers from jars

Sorting through the jars of vinegar flowers

I have chosen to keep--

- 50V full submersion delphinium and larkspur to keep track of how they are dissolving in the distilled vinegar

- 50V full roses, 7V full roses, and ACV full rose to test how they hold up over time; the ACV is not supposed to keep the rose/carnation preserved well, b

- 50V partial rose to observe the color changes in the petals, since this one is much more vibrant that the other vinegars

- ACV partial delphinium and larkspur because the larkspur was the only partial submersion delph/lark that did not 'sag' in the jar, its stem is still fairly straight and the color of the petals is still close to what it originally was (although a little muted)

2:15PM, lab

removing flowers from vinegar jars

General observations: the double parafilm + plastic lid seal seems to have been an effective seal—parafilm was cut where the threads were, but the top remained tightly sealed and intact. no mould on any of the flowers.

1. full ACV delp and lark - removed parafilm disk with tweezers; brown film on underside; unclear if brown residue is a result of the vinegar or dissolved, stringy, gooey flowers. The smell of apple cider vinegar was very strong, with an undertone of alcohol or fermentation to the point of slight rottenness

2. partial ACV rose - turned orange; much condensation on the petals;

3. partial 7% rose - when wafting, it smells of rose, slight rot, and; much condensation on the petals;

2 and 3 are similar in color—orange and red tie-dye like. The color is coming off both flowers' petals. The stems are strong. The petals are softer than they were initially, but you have to tug them pretty hard to get them to come off. Decided to keep these two roses and put in the fume hood to dry out of curiosity—perhaps the recipe intended that the roses should be initially treated with vinegar and then dried.

4. partial 50% delph and lark - very strong smell of vinegar/acid; the stems, where they were under the acid, remain strong and turgid; where the stems were outside the acid, they have gone limp; despite the ease with which the petals fell off the flowers before they were processed, now the petals are more difficult to remove. Cleaning out the jar of the 50%, it smells like flowers that have been kept in water for too long and are finally taken out.

5. full 7% delph and lark - comparatively little smell; the flowers themselves smell of rotting stems that have been in a vase too long; the stems are soft and yield beneath the tweezers' pinch; delphinium petals were firmly attached while the larkspur petals came off easily

6. partial 7% delph and lark - smells like rotting flowers; NJR: it smells a bit like artichokes; the stems are soft and yield beneath the tweezers' pinch; delphinium petals were firmly attached; the larkspur petals have changed from purple to brown-green

7. set apart ACV rose and 7V rose on a ceramic plate to dry in the fume hood -- we were curious to see what would happen to the petal color/overall look of the flowers when they were dried after being submerged

The dried vinegar roses were placed in jars on January 12, 2016 after they were fully dried--