BREAD MOLDING RECIPES FIELD NOTES

NAME: Raymond Carlson & Jordan Katz

DATE AND TIME: September 21, 2014

LOCATION: New York, NY

SUBJECT: Making the Bread Molds

1. Choosing Recipes

Bread Mold

To mold the bread we are following the recipe in BNF MS 640, fol. 140r

BNF MS 640

fol. 140r

<title id=“p140v_a1”>To cast in sulfur</title>

<ab id=“p140v_b1”>

To make a clean cast in sulfur, arrange the pith of some bread under the brazier, as you know how to do. Mold whatever you want & leave it to dry & you will have a very clean work.</ab>

<note id=“p140v_c1”>

Try sulfur passed through melted wax, since it won’t catch fire & won’t make more little eyes.</note>

<title id=“p140v_a2”>Molding and reducing a big piece</title>

<ab id=“p140v_b2”>

Mold it with the pith of the bread just out of the oven, or like that aforementioned, & and in drying out it will diminish & by consequence so too the medal that you have cast. You can, in this way, in lengthening out or enlarging the imprinted bread, vary the figure & from one face make several quite different ones. The bread straight from the oven is best. And that which has been reheated twice shrinks more. You can cast sulfur without letting the imprint on the bread dry, if you want to cast it as large as it is. But, if you want to let it diminish, let it dry either more or less.</ab>

Additional Recipe Information

Memoire sur les avantages que la province de Languedoc peut retirer de ses grains, considérés sous leurs differens rapports avec l'agriculture, le commerce, la meunerie et la boulangerie. Avec figures. Par M. Parmentier

__http://documents.univ-toulouse.fr/150NDG/PPN042613957.pdf__

f.282-283 discusses “levain,” and different types of sourdough that can be used. It also explains what effect “old sourdough” vs. “new sourdough” would have.p.358 in the pdf version [unnumbered page] shows pictures of what the oven would have looked like

Brazier – what does this mean??

- BNF MS 640, fol.140r says to arrange the pith of the bread under the “brasier,” which seems to indicate under the flame of the oven. We wondered if a broiler would simulate this kind of flame more because the flame comes from the top. The answer seems to be found elsewhere in the manuscript:

BNF MS 640, fol.013v brasier

Celle qui est de la teste du crapault et qui ha la figure du crapault naturellement paincte comme tu as veu est la plus excellente on tient que si on mect de la pouldre dicelle sur un brasier en la chambre de quelques uns de nuict quilz ne pourront se mouvoir ne parler ne donner empeschement aux larrons.

[NB: We disagree with the translation of this text. Where it says “if you throw some such stone powder or a brazier,” the word “sur” should be translated as “on a brazier” - meaning, throw the stone powder on an oven-like thing or into an oven.]

We decided to test one of the variables outlined in the recipe on fol. 140v, which gives instructions on how to shrink a form that has been molded in bread.

Bread Recipes

We struggled to find a simple recipe for bread outlined in historical sources.

We were heartened by a 2010 blog post by Professor Ken Albala, who explains that when it comes to baking bread, his personal inclination is not to follow a specific recipe: “Making bread, I do not want to measure anything. I want to feel the dough, let it go where it wants, knowing full well it will always be different depending on the weather and the whim of the Gods.”

__http://kenalbala.blogspot.com/2010/01/no-recipes.html__

With this in mind, we consider that the very simple ingredients for bread (flour, starter, salt and water) were likely so often combined in different proportions that we should concern ourselves less with finding a specific recipe than testing specific variables of the bread.

With this in mind, our principle recipe was an Emeril recipe for sourdough bread, just as a start to see how “modern” bread would work for the molds.

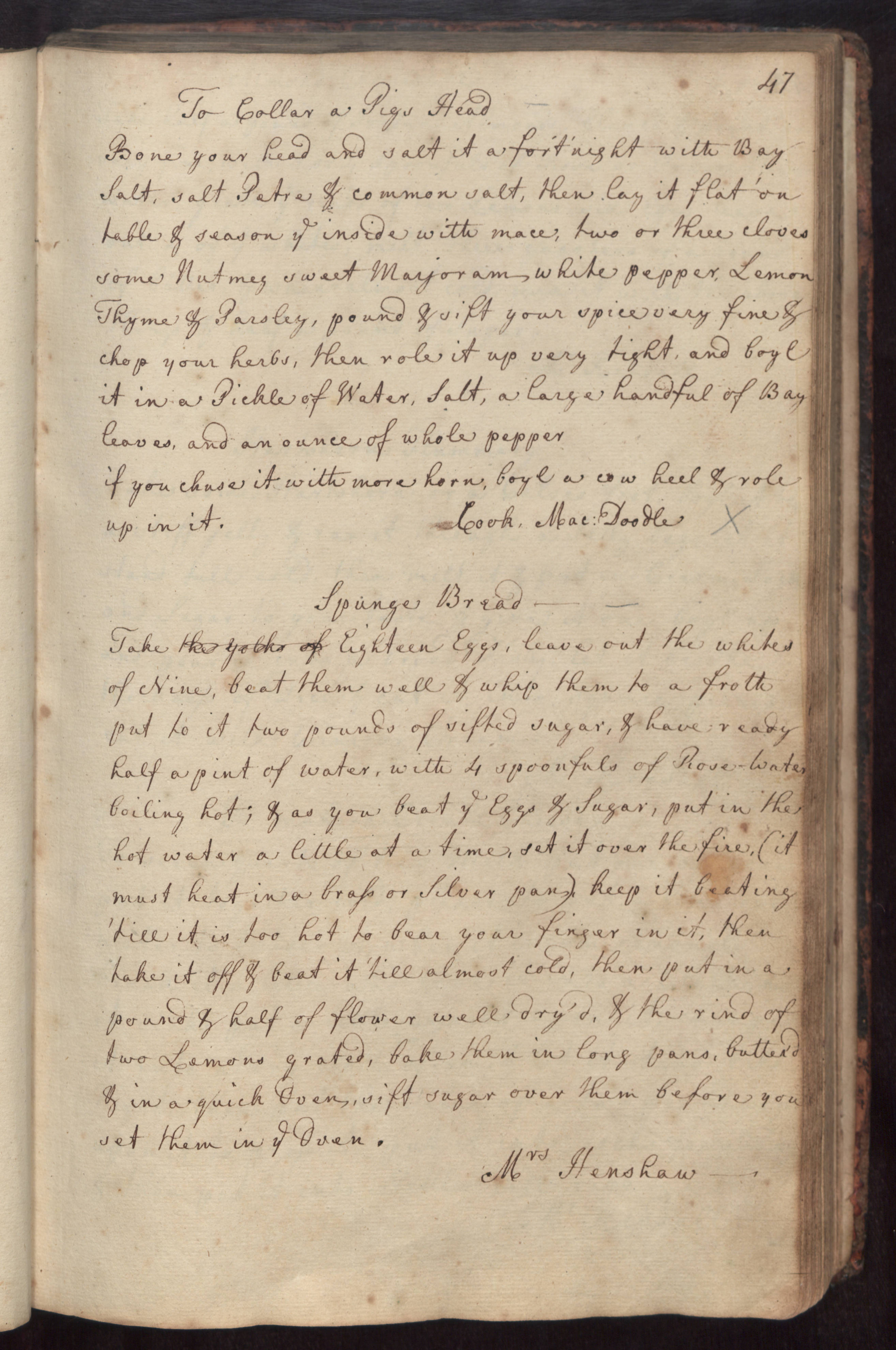

As an alternative recipe, we tried an early 18th century bread recipe that required no starter/yeast but instead relied on eggs to leaven the dough: English manuscript from the 1700s in the Szathmary Collection at the University of Iowa, which is available through the DIY History project. Here is a__link to the manuscript__, and the recipe is found on fol. 47r:

“Take eighteen eggs, leave out the whites of nine, beat them well & whip them to a froth put to it two pounds of sifted sugar, & have ready half a pint of water, with 4 spoonfuls of Rose-water boiling hot; & as you beat the eggs & sugar, put in the hot water a little at a time, set it over the fire, (It must heat in a brass or silver pan) keep it heating ’till it is too hot to bear your finger in it, then take it off & beat it ’till almost cold, then put in a pound & half of flour well dry’d, & the rind of two Lemons grated, bake them in long pans, buttered & in a quick oven, sift sugar over them before you set them in the oven.”

2.INGREDIENTS:

1. Starter -- furnished to us by Professor Pamela Smith and fed very dutifully over the course of the past week by Jordan!

2. Flour (Whole Wheat and Rye) -- we are testing two different types of flour, both stone ground. One type of flour is Whole Wheat, the other is Dark Rye.

3. Salt - Morton Iodized Salt used just a pinch at a time!

4. Water - “New York City’s finest!” to quote every local waiter who has ever made this joke.

3. Baking the bread

Principle Recipe

Step 1: Pour 1.5 cups of starter into the bowl, followed by 2 cups of flour, and ¾ tsp of salt.

Step 2: Knead the bread dough by hand

- The whole wheat flour seemed more dense, making it less malleable

- The dark rye flour had a stickier, lighter consistency, which made it more malleable.

Step 3: Leave bread dough to rise for at least 30 minutes

Step 4: Bake bread in oven preheated to 400 degrees for 45 minutes.

Alternative Recipe (halved)

Step 1: Add 4.5 egg yolks and 4.5 eggs to a bowl. Stir until a bubbly froth develops along the edges.

Step 2: Add 1 pound of sugar.

Step 3: Add a half-cup of water at a near boil and 2 spoonfuls of water also at a near boil. These two spoonfuls of water substitute for the rosewater, which the recipe had called for.

Step 4: Stir. Do not add shaved lemons, as the original recipe instructed.

Step 5: Pour into a greased tin and bake until the bread appears to have risen.

4. Molding the bread

We had five test objects to mold:

1. The metal cylindrical lid of a vitamin bottle (used to test “shrinkage”)

2. An ovular brooch

3. A flat, irregularly shaped pendant

4. A jeweled lid

5. A pendant with crossed wires

Shrinkage Test

We first baked a loaf of whole wheat bread at 400 degrees for 45 minutes. After the bread was finished in the oven, we removed it and cut it open horizontally with a knife. We immediately pressed objects #1, #2, and #3 into the pith of the bread. We left them imprinted into the bread for three minutes.

Upon removing the cylindrical lid from the molds, we measured the diameter of the mold made by the lid. We then let it dry for 10 minutes, and then we returned it to the oven for 10 minutes. We measured the diameter of the mold shape. Noticing little change, we let it dry in the fridge for 10 minutes, and we returned it to the oven for 10 more minutes. We measured the diameter of the mold shape again. We returned the bread to the fridge for 10 minutes, we put it in the oven for another 10, and then we measured the diameter of the mold shape once more.

We repeated this process for the dark rye bread. We noticed that when the whole wheat bread emerged from the oven splits had emerged along the side, and we therefore decided that for the further bread trials we would shape the bread dough into a flatter shape prior to placing it in the oven.

Below is a chart showing our measurements of the diameter of the impression in the bread molds:

| Diameter out of oven |

Diameter after 1 reheat |

Diameter after 2 reheats |

Diameter after 3 reheats |

|

| Whole Wheat Flour |

37cm |

37cm |

35cm |

34cm |

| Dark Rye Flour |

37cm |

36cm |

35cm |

34cm |

Pith Test

We then baked two more loaves of bread, one whole wheat, one dark rye. In this second iteration, we baked the bread for 45 minutes. We then removed it from the oven and cut it in half horizontally. We promptly scooped out the pith of both sides of the bread and pressed objects #1 and #4 into the scooped out wads of pith. Our initial thought had been to stretch out the pith, as the recipe in the manuscript mentioned “lengthening out or enlarging the imprinted bread,” but the doughy form felt too weak to our touch to extend without breaking into fragments. We therefore used this process to test how well the pith, when pressed tightly against the physical form, could make an impression of the objects.

Alternative Recipe Test

After baking the bread for the alternative recipe for 30 minutes, we removed it from the oven, cut it horizontally, and pressed objects #1 and #4 into the pith. We observed that the dough was more dense, with smaller crumbs and less air pockets. Unlike the other forms of bread, the impression seemed more detailed: one could almost read the lettering on object #1. The spongy character of the bread (as attested to by its name of “sponge bread”), also prevented any splitting or crumbling, as the form seemed to absorb the insertion of the object more readily than the rye and wheat bread.

However, this is a less durable mold, as it is quite breakable and flimsy, so one must be careful when transporting it.

NAME: Raymond Carlson & Jordan Katz

DATE AND TIME: September 14, 2014

LOCATION: New York, NY

SUBJECT: Selecting a recipe

Searching for Bread Recipes

Locating a recipe in Renaissance sources for a simple bread proved surprisingly tricky. I could not find a basic bread recipe in Hugh Plat's Jewell House of Art and Nature and Delights for Ladies. Ginger bread and biscuit bread could be found, but these are specialized breads that seem out of synch with the needs for a bread mold. Searches of other manuscripts through the Wellcome Library and Early English Books Online similarly did not turn up a basic bread recipes.

Question: Was the making of bread so commonly understood that such a recipe was rarely written down in recipe books? Were specialty breads (ginger bread, biscuit bread) the only recipes worth preserving? Is this because bread lacked an element of "secrecy" or specialization?

Sponge Bread?

The most straightforward bread recipe I found was from an English manuscript from the 1700s in the Szathmary Collection at the University of Iowa, which is available through the DIY History project. Here is a link to the manuscript, and the recipe is found on fol. 47r, reproduced below.