Table of Contents

Dark red text has been formatted as certain heading types. To ensure the table of contents is rendered correctly, make sure any edits to these fields does not change their heading type. |

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Private apartment, 405 West 118th Street, 10027 New York.

Subject: Selecting a design

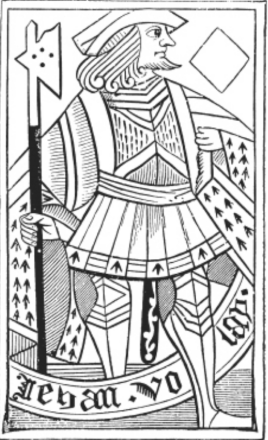

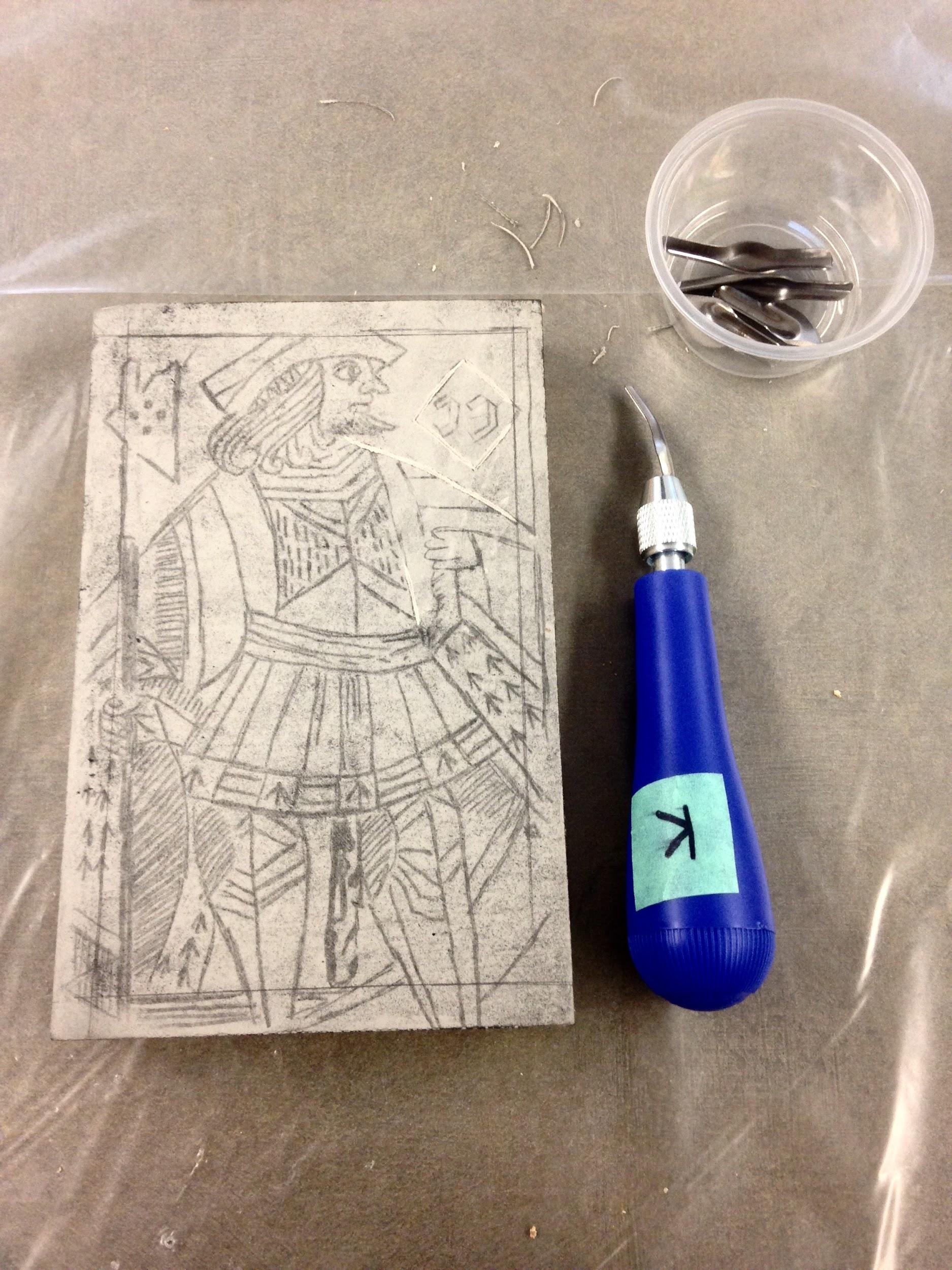

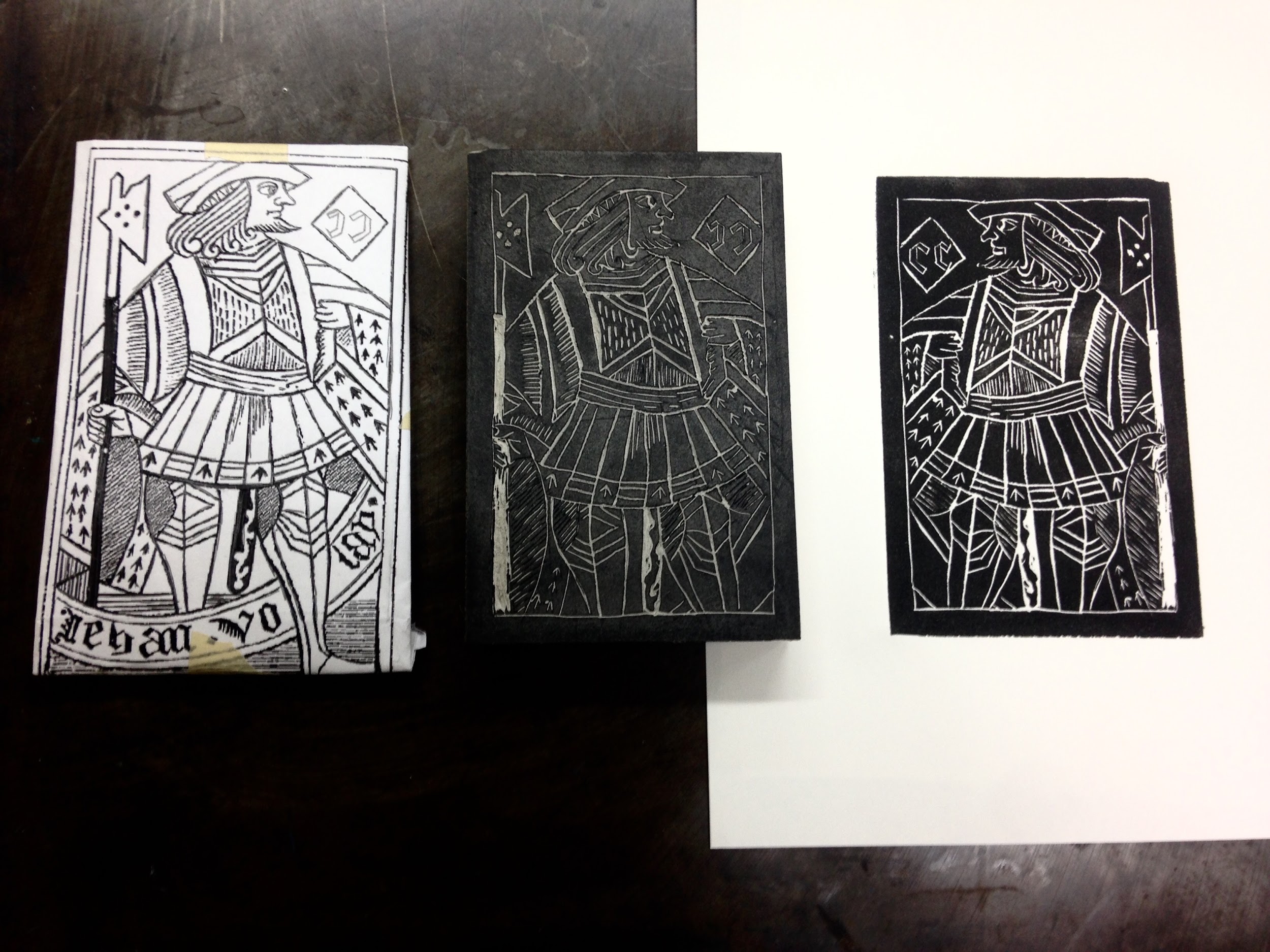

As of upcoming week we will be learning various printmaking techniques, the first of which is linocut. As a design, I wanted to use an early modern woodblock print.

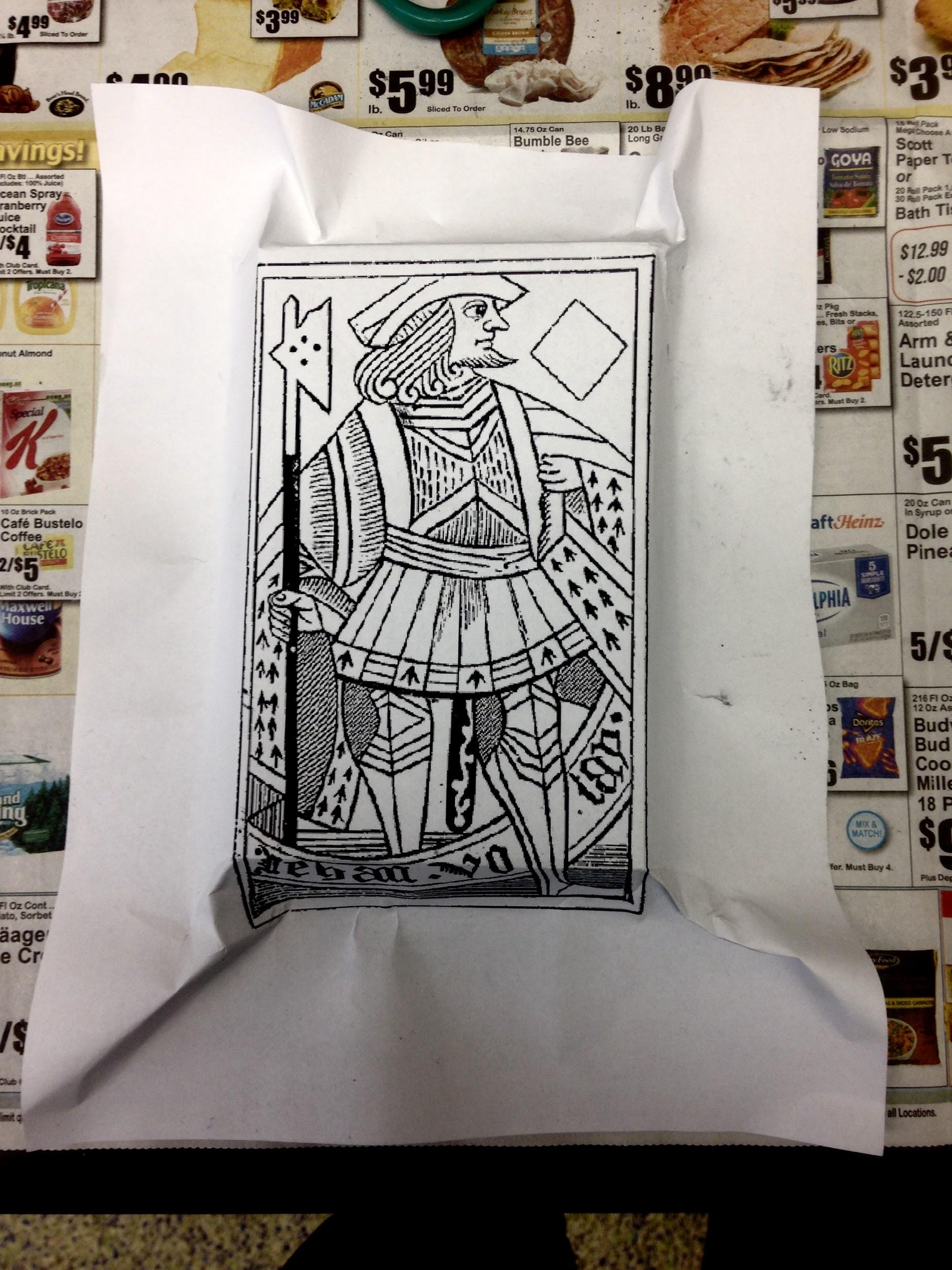

I chose ‘Jack of Diamonds’, an anonymous woodblock playing card from ca. 1400 (see image).

I adapted the size of the image to make sure it would fit on a 5x7 inch lino block. I then printed the image on a regular A4 piece of paper.

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Havemeyer Hall, Chandler 260, Columbia University, NY, NY 10027

Subject: Preparing the transfer of the design; making a border/margin

Materials:

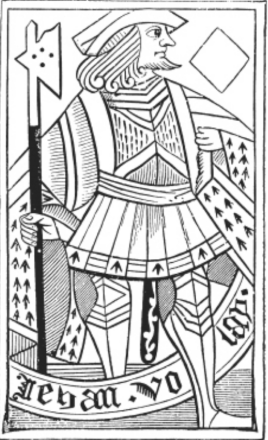

5x7 inch Lino plate placed on a woodblock

Tools:

Ruler

Pencil

The first step in the preparation of transferring the design (following Naomi Rosenkranz’ instructions), was to create a margin of 0.5 inches on the lino (which was placed on a woodblock to make it easier to hold).

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Havemeyer Hall, Chandler 260, Columbia University, NY, NY 10027

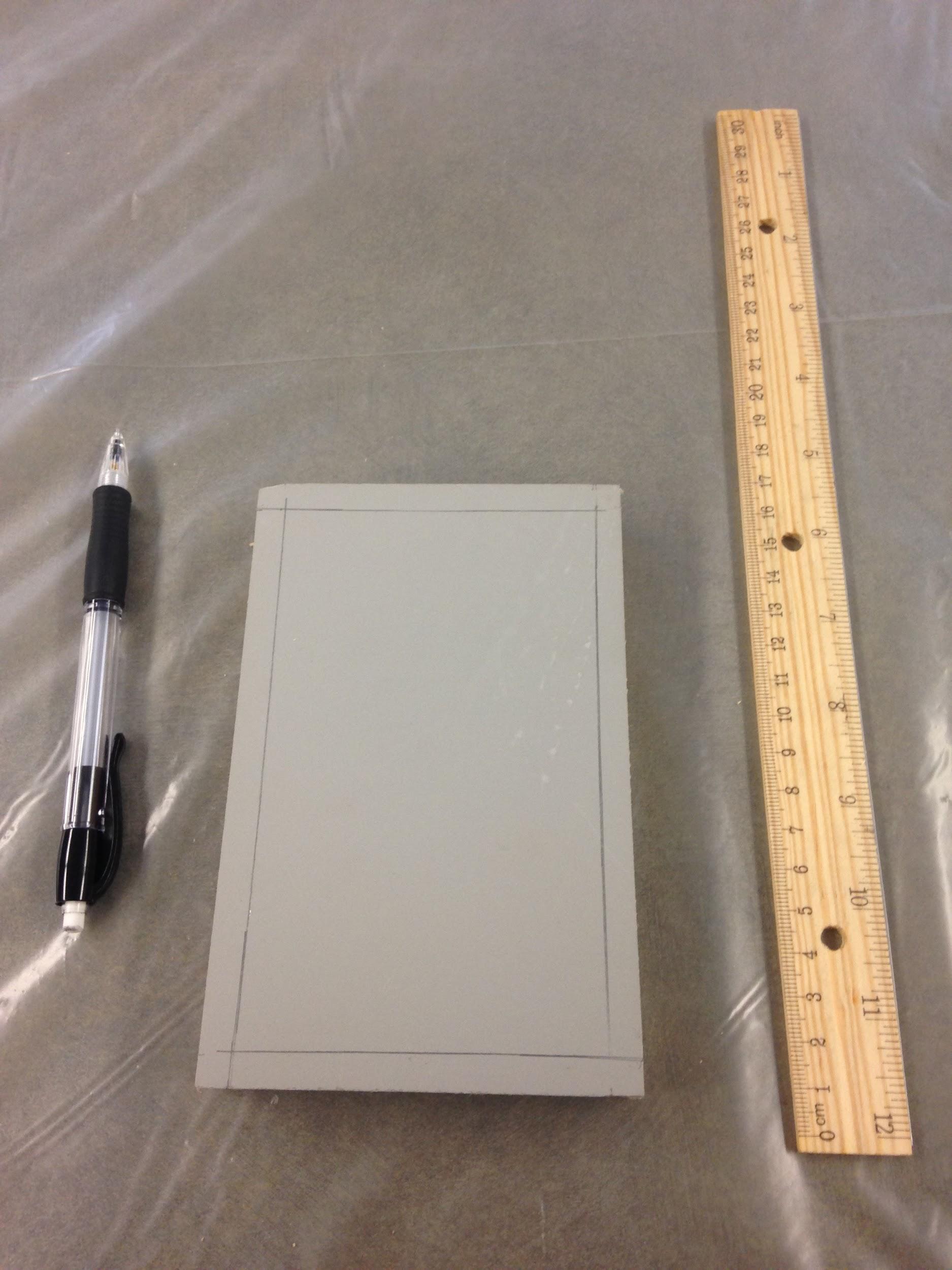

Subject: Preparing the transfer of the design; darkening the backside with charcoal

Materials:

5x7 inch Lino plate placed on a woodblock

Charcoal

Printed image/design

Tools:

Charcoal

The second step in the preparation of transferring the design, was to blacken the underside/backside of the image with charcoal sticks. This was the easy part. I wasn’t sure how thick the layer of charcoal had to be, but I reckoned, I had to just try and see.

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Havemeyer Hall, Chandler 260, Columbia University, NY, NY 10027

Subject: Preparing the transfer of the design; placing the design on the lino block

Materials:

5x7 inch Lino plate placed on a woodblock

Printed image/design, darkened with charcoal

Tools:

Tape

Next, we had to place the underside of the design, covered in charcoal, on top of the linoleum. This was more tricky then it looked, as in doing so I couldn’t see which part of my design would go inside the borders and which part would not. I used tape to attach the print to the block, preventing it from moving in the process of transferring the design. I learned that they would probably have used wax or glue for this in the early modern period.

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Havemeyer Hall, Chandler 260, Columbia University, NY, NY 10027

Subject: Transferring the design onto the lino block

Materials:

5x7 inch Lino plate placed on a woodblock

Printed image/design, darkened with charcoal and attached to the lino block

Tools:

Pencil

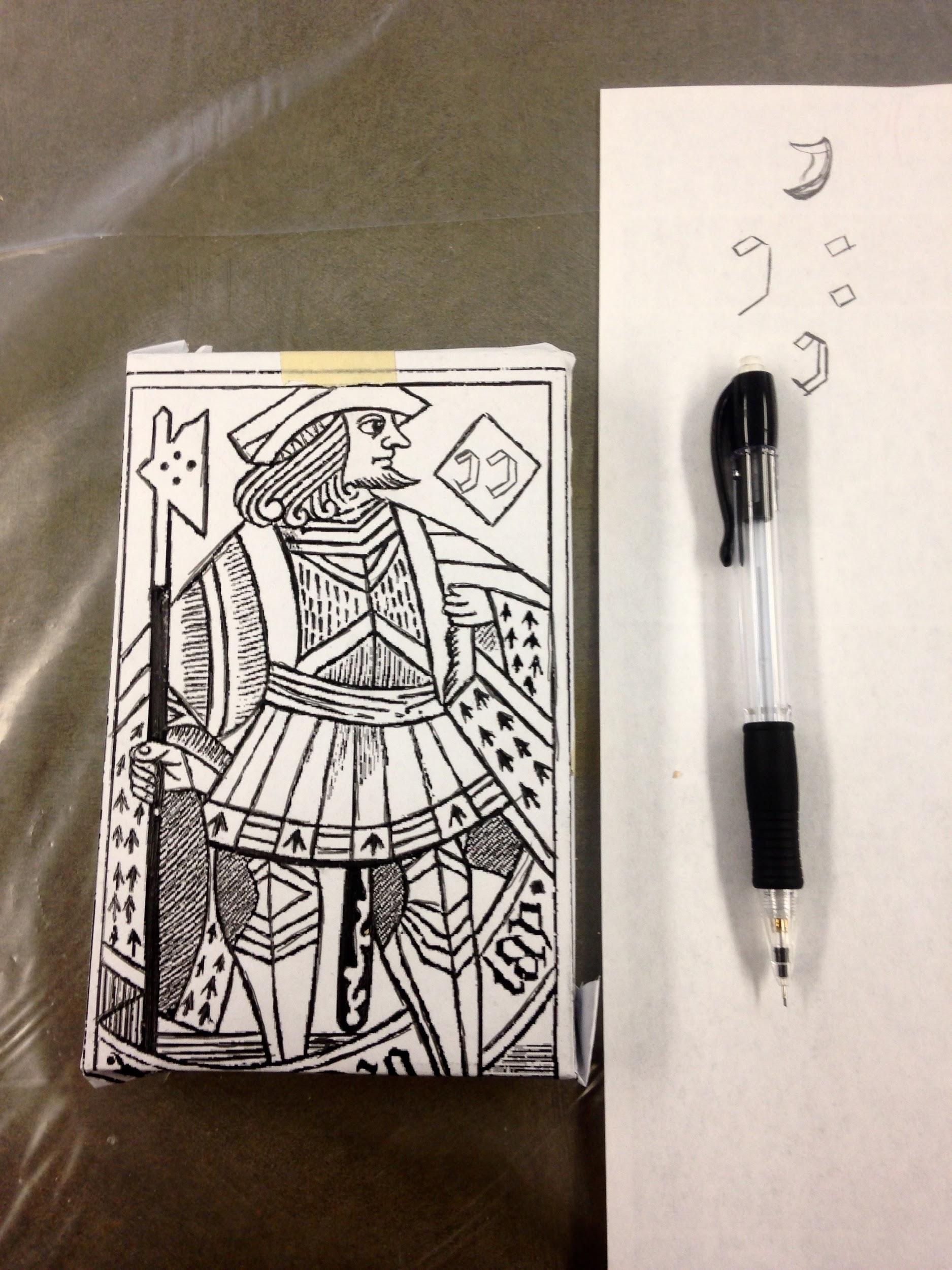

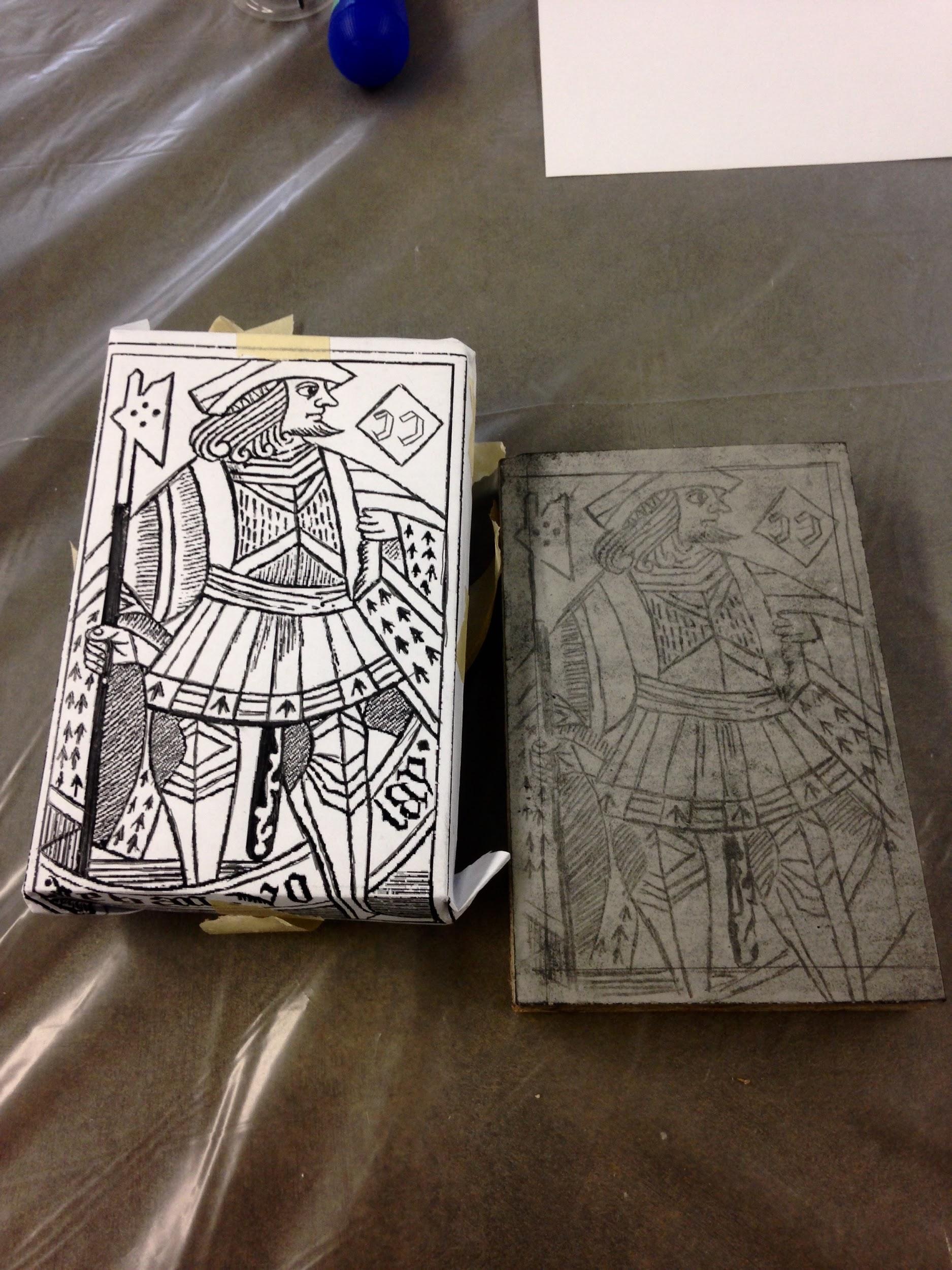

Now we had to actually transfer the design of the image onto the lino block. For this we used a pencil, with which we had to trace every line, shape and element in the image.

Tracing the design of the playing card onto the linoleum took longer than I thought – especially because I had a lot of lines to transfer over. Because of this amount, it was also difficult to see or remember which lines I had already traced with the pencil. Removing the paper to check was not an option, as new lines drawn after re-placing the image back onto the lino would be misaligned. Holding the image into the light and moving the block in various directions allowed me to recognize shades of silver -- that is, traces of where the pencil had already been.

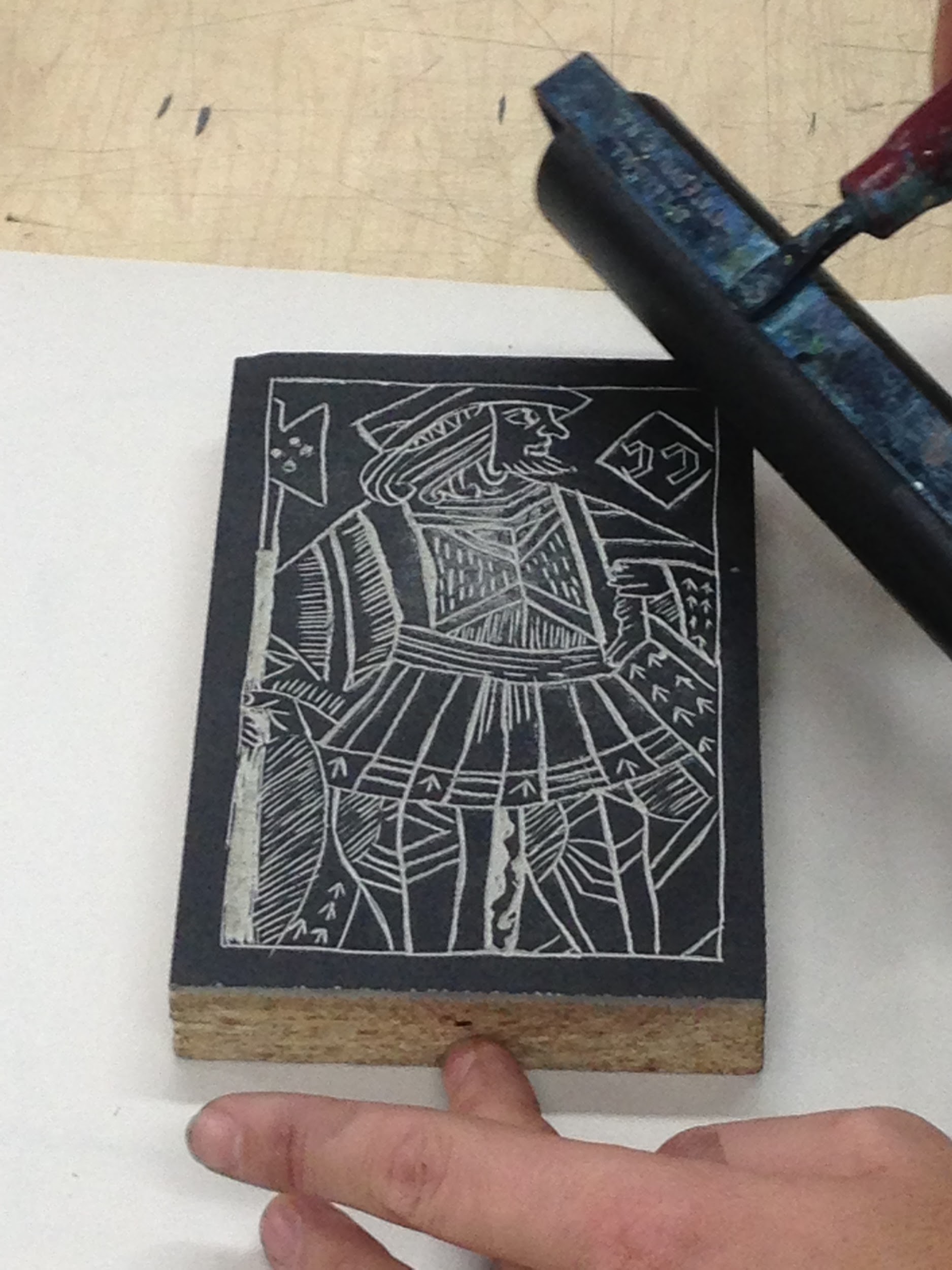

Once I had traced all lines, I decided to add my initials in the diamond shaped figure on the top right of the image. As the design would be inverted in the printing process, this meant I had to write my initials backwards as well. I practised on a piece of scrap paper first and then drew the letters on the printed image. I then carefully removed the printed image from the lino block to find my design ‘printed’ onto the material in lines of charcoal.

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Havermeyer Hall, Chandler 260, Columbia University, NY, NY 10027

Subject: Linocutting

Materials:

5x7 inch Lino plate placed on a woodblock

Tools:

Lino cutter (Number 1)

I could choose to either cut out all the white parts of my image, choosing to only print the black charcoal lines. Or I could reverse the black and white in the original print and thus print all of its white parts. This would mean I would have to cut out all the charcoal lines.

As there were quite a few dine details (such as arrows and circled/round shapes) in the design, I decided it would be easier to follow the black lines, then to work my way around those difficult shapes.

As I didn’t have any large areas of black or broad lines to remove, I choose the fines cutting tool (number 1).

Bodily knowledge, material and technical understanding

Although I had already worked with lino before, I forgot how resistant this material actually was (this may in part be a result of the low temperature in the room, which could have caused the the lino to become somewhat harder. It might become more malleable after a while and from the heat of my hands) and how much bodily force you actually have to use in order to cut it out of the block. It took time for me to understand how to control my own bodily force and how much of it to actually use. This required both getting to know my own bodily strengths (and how to control them) better, as well as understanding lino, its material properties and how it responded to my bodily engagement with it. So these two kinds of knowledge had to fuse and work together as it were in order for me to improve my cutting technique.

It also took awhile for me to find a good or comfortable bodily position and way of holding the cutting tool as well as the right angle for cutting in order to create a specific kind of hollow.

This too, requires knowledge and experience. It demands familiarizing yourself with the tool and what you can do with it, how to wield it in order to get a desired effect.

Each of these things can only be learned and honed through practice and experience.

Physically demanding and laborious

I soon experienced how demanding the cutting process is on both your body and mind:

Hands:

Even though you only need one hand to hold the cutter and to remove the lino, your other hand is essential to the working process too. While using one of your hands to cut away the material you do not want printed, your other hand is holding the lino block,

preventing it from moving, so you have a steady surface to work on. After a while, I had

a cramp in both of my hands and was in need of stretch.

Shoulders and back:

I noticed that my shoulders and back also started to hurt at one point, having been hunched or hanging over my design in the same position for too long. I am not sure if this was a sign that my posture was wrong or if my body simply had to get used to this kind of work.

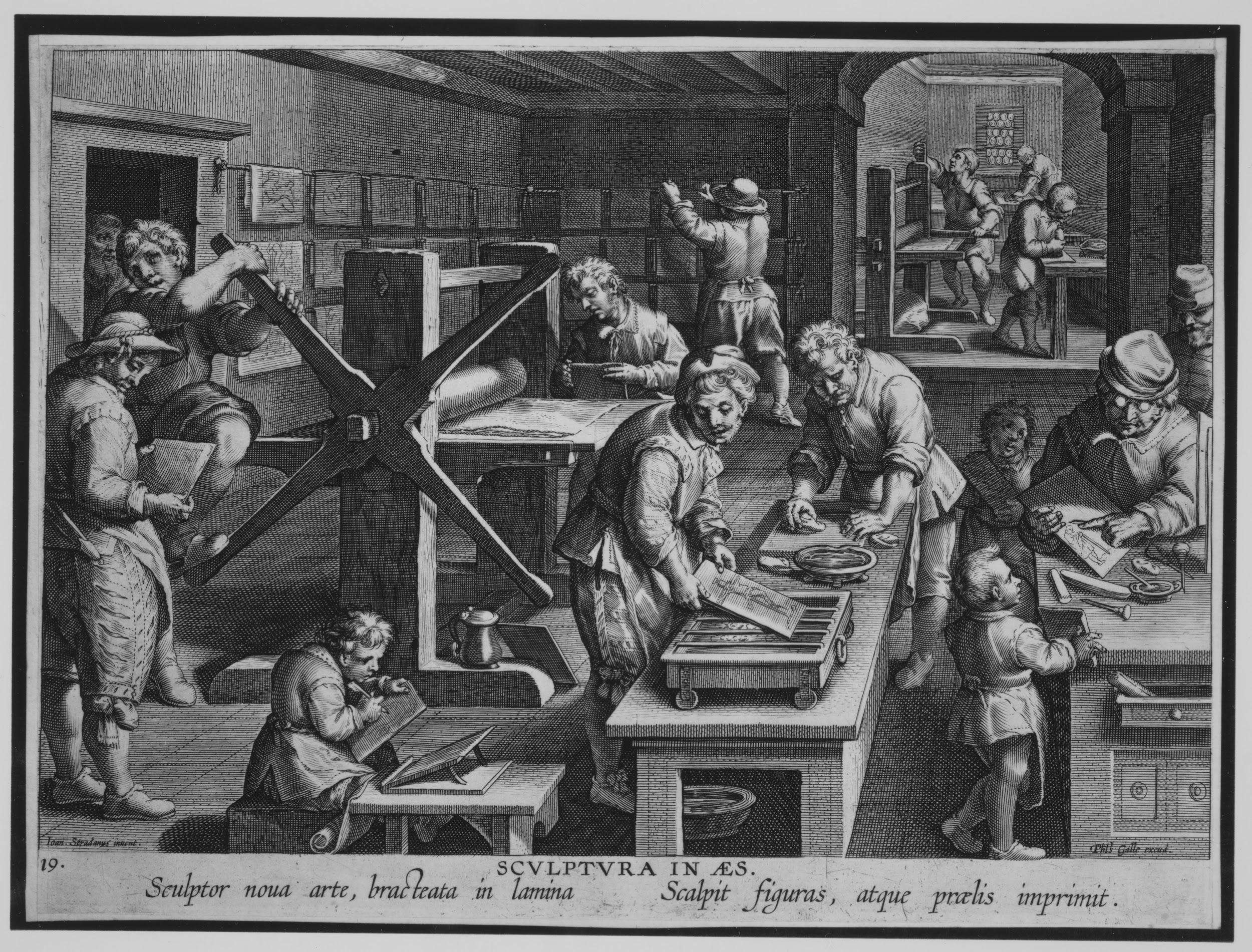

Eyes:

My own experience of preparing a linocut print made me better understand Ad Stijnman’s claim that the engraver in Stradanus’s print shop was depicted wearing glasses, as“ close-up work may have made him near-sighted” (see the right side border of the figure below).1 As my design contained many fine lines and details, I had to squint my eyes and move closer to my work to focus on the various shapes and forms and make sure I was tracing the correct line. This was very tiring on my eyes and I needed to take regular breaks to ‘stretch’ my eyes.

Mind:

Although therapeutic at first, cutting the lino became tiring on your mind after a while as it demands your undivided attention. Having to follow the design precisely (if you do not accidentally want to alter it), you cannot afford to get careless or let your mind wander off for even a little as that would risk sliding through the lino too fast, either cutting yourself, or gouging a line or whole into the material in a place where you wouldn’t want it. Once a groove has been created, it can be extended, thickened, or deepened, but it cannot be removed.

This also made me realize that this material (probably similar to that of wood) does not

allow much room for experimenting or trial and error while in the process of making the

print. At least not when working with a fixed design that is not supposed to be or you do

not want altered.

In conclusion: I can only imagine what physical and mental exhaustion people most go through (and have gone through) when working on multiple designs and under possible time constraints.

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Private apartment, 405 West 118th Street, 10027 New York.

Subject: Linocutting

Materials

5x7 inch Lino plate placed on a woodblock

Tools:

Continued cutting the lino.

Cutting order

I realized I probably should have started working from the bottom up as I noticed I was smudging the lower edges of my design with the side of my hand holding the tool as I was trying to cut out the upper lines in my lino block.

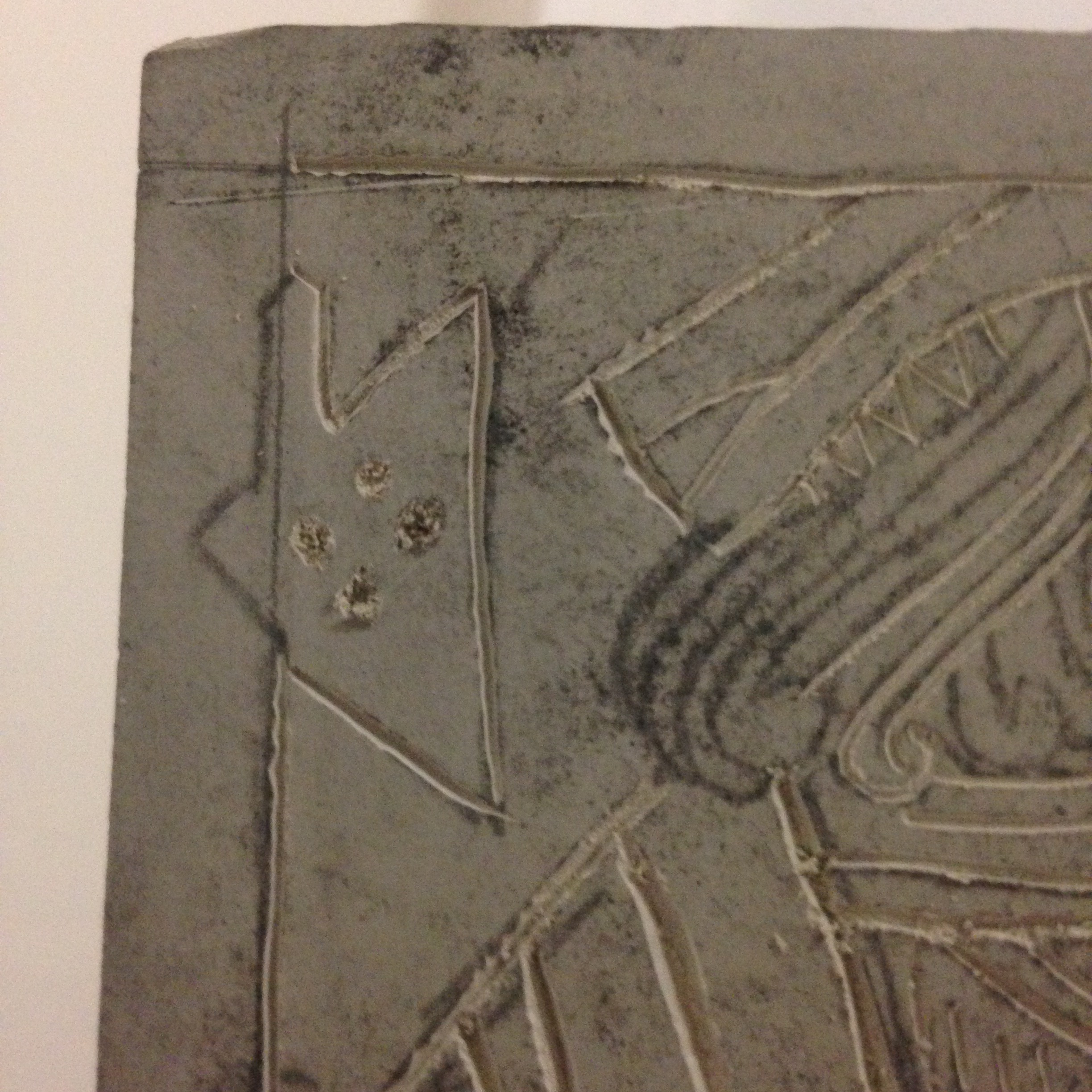

Cutting out various lines and shapes; trying out news techniques

The left upper corner of my design contained small dots/circles. Yet how do you create those with a rather rough cutting tool? Trying to goug a circle in the same manner as I used to create would probably not create an evenly shaped figure. I decided to try a new technique.

Instead of sliding through the linoleum horizontally, I placed the cutting tool perpendicular onto the linoleum and then rotated it 360 degrees (while pressing it onto the surface), in doing so removing the linoleum in one singular (and smooth) movement.

I took a risk on using my tool in a less traditional way (traditional here meaning my common way of having wielded the cutting tool); that is, I was experimenting, not knowing what would happen or what the result would be. But I took a change nevertheless, because in that moment, I believed it could work.

I equally struggled creating several narrow lines parallel to one another on a relatively small surface area. Either cutting tool is not suited for producing such fine details or I need more experience in knowing how to wield my cutter to produce such effects.

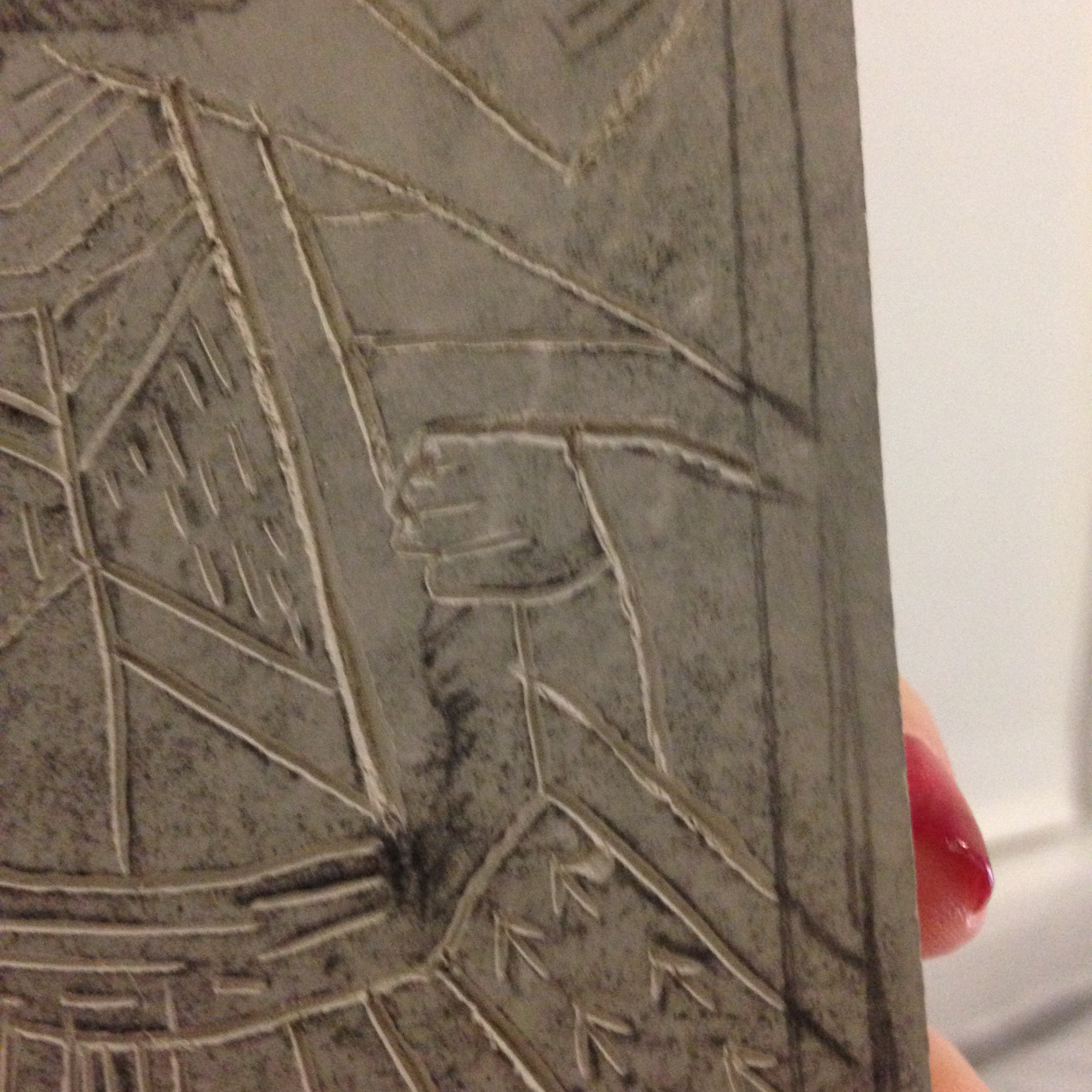

I also tried a new technique when attempting to create a curve for depicting the hair of the figure in my design (see image below). While sliding through the lino block, tracing the curve, I simultaneously and slowly moved my lino block in the opposite direction. This allowed me to keep my tool in one place and not force my hand into an awkward position. This worked quite nicely as it created it a smooth, even curve (see image below) – just as I had hoped.

Errors

My first error: in trying to create a fist-shape in the lino, I accidently removed too much and it has deformed the shape (see image)

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Private apartment, 405 West 118th Street, 10027 New York.

Subject: Continue linocutting

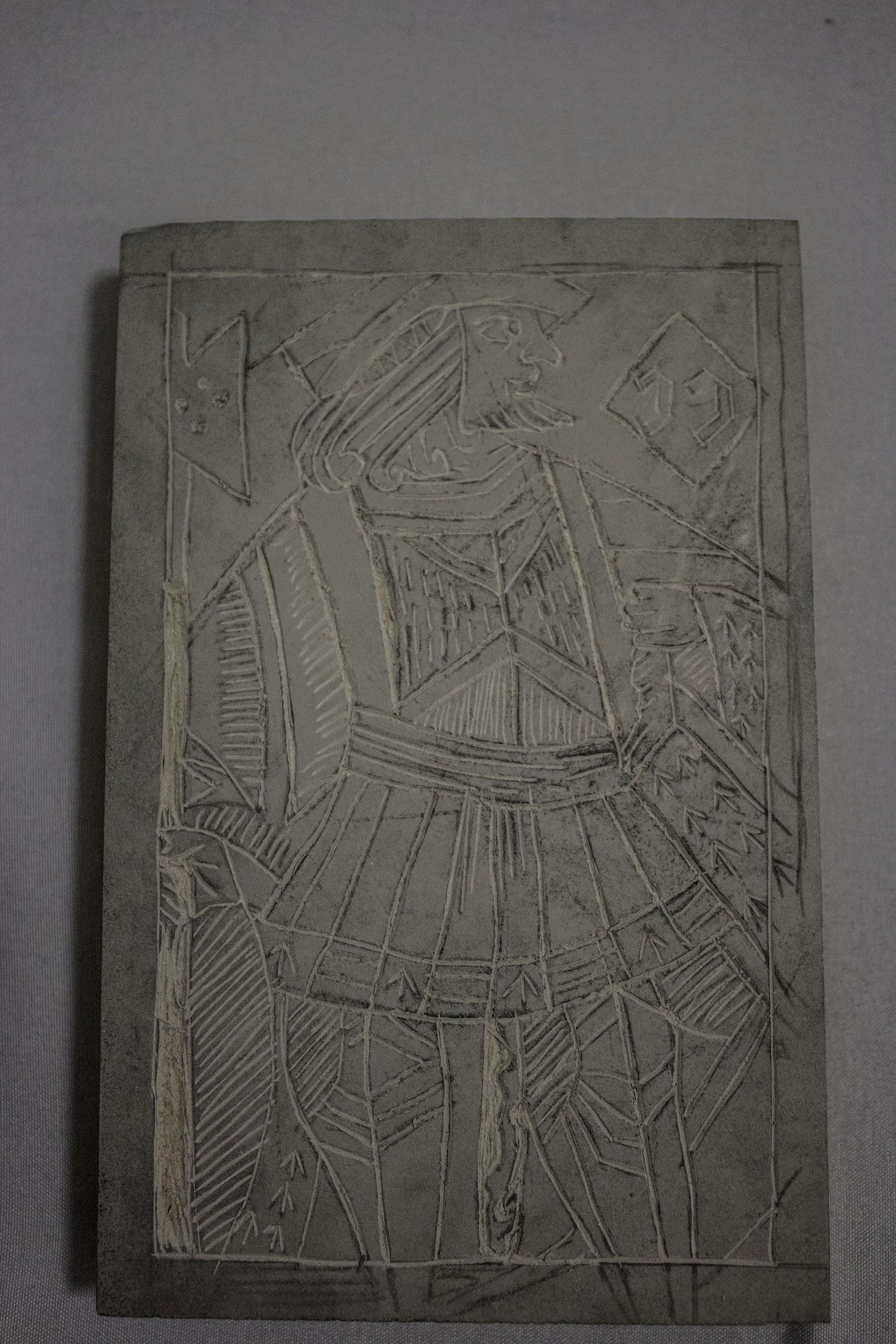

Today I finished my linocut (see image). I noticed it went easier than last time. That is, I was less hesitant to cut into the lino or scared to cut myself, having already had prior experience with the tool as well as the material. However, it was precisely because I was more ‘comfortable’ that I was less attentive of other things. E.g. I forgot that the charcoal lines could be smudged and I accidently erased part of the design with the side of my palm. I thus had to redraw it with a pencil.

I reckon this error was also partly due to the fact that several days had passed since I had worked on my linocut and thus had forgotten what to keep in mind or pay attention to.

Perhaps this is another aspect of processes of making and manual labor: it requires repeated and continuous practice, not only to learn the skills required to perform a task, but also to make for each step of and things to keep in mind about the process to become part of a routine way working. A routine that enables you to proceed in an almost automatic fashion and without much reflection.

I found it hard to know how much lino had to be carved out to create the appropriate depth for printing. That is, what is the minimum depth of an incision that no longer allows ink from the roller to come in? As is the case with most things in historical reconstruction: I will have to try and see. Trial and error.

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Teachers College, 525 W 120th St, New York, NY 10027

Subject: Printing the linocut

Tools:

Printing press

Rubber brayer

Putty knife

Two sheets of newsprint paper

Printing paper

Felt

Sponge

Materials:

Linocut

Ink (water based)

The printing process

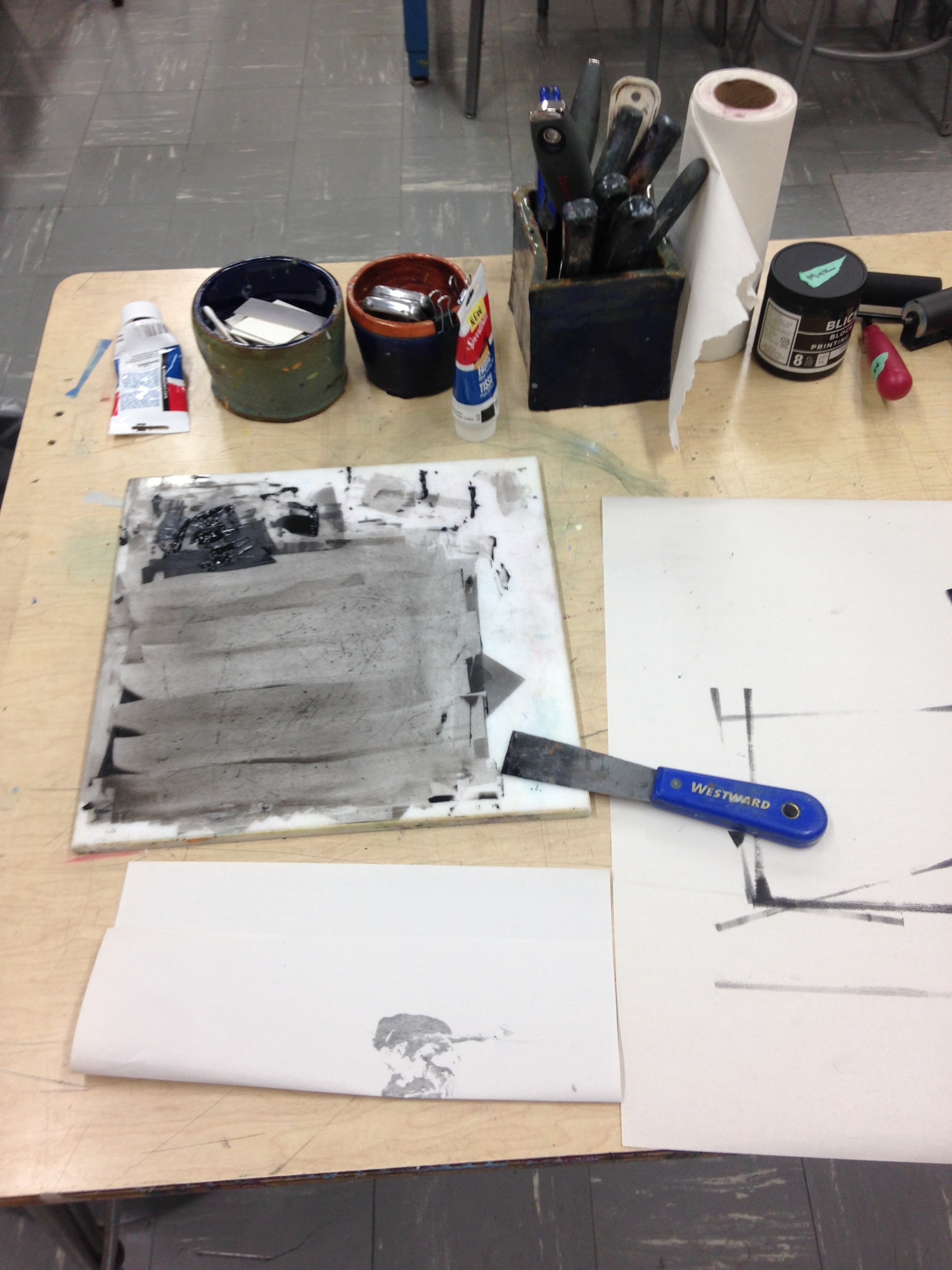

The first step in printing the linocut was to check the pressure of the press (as with the intaglio printing process).

Check if the ink on the inking plate had not dried out. If yes, scrape it off/remove it and replace with new ink (image 1 & 2)

In case of new ink used, divide it over the printing plate with a putty knife (image 3).

We used water based ink as opposed to oil-based ink (which we used for the intaglio

printing).

This ink was much more liquid and less paste-like as the intaglio printing ink.

Spread evenly with a rubber brayer (there are various kinds of rubber - hard, soft, etc., but unfortunately Caroline was not sure which one she was using at the time).

In doing so, make sure there are no ink blobs on the printing plate as this will be transferred onto the brayer, causing an uneven layer of ink to be transferred onto your lino block as well (image 4).

Roll the brayer over your linocut, to cover the block with ink. Move the roller in various directions (horizontally, from top to bottom and vice versa; vertically, from the left to the ride side and vice versa; and diagonally, from the upper left to the lower right corner and vice versa). Repeat this several times and make sure the ink is spread evenly over all raised parts of your block (image 5).

It is important to immediately move on to the printing press so as to make sure the ink won’t dry.

Place a sheet of newsprint paper on the bed of the roller press (as in the intaglio printing process) to prevent staining.

Put a sheet of printing paper on top of your inked lino block and gently rub over the sheet your hand to make sure it sticks to the block (and to prevent the sheet from moving in the press).

Place an extra sheet of newsprint paper on top of your printing paper and the lino block to prevent ink from staining the felt.

Keep your left hand on the lino block (so it won’t move) and use your right hand to fold the two sheets of felt over it.

Then, while keeping your right hand on top of the block (and the felt), gently remove your right hand (which was underneath the felt).

Use your hips to push the bed of the press towards the roller. Once underneath, remove your hand and use the handle to press the roller on your lino block and allow it to be pushed underneath.

You will feel a hard kickback as the bed of the press (with your lino block on top) moves underneath the roller to the other side.

Once on the other side, lift the felt and remove the newsprint sheet to see your print (images 6 & 7)

Then place your printed image on a drying rack to let the ink dry.

Clean the block with a sponge and water if you want to reuse your block for printing (image 8).

The result:

I found it difficult to reflect on the process of printing linocut, in part because you have to act fast in order to prevent the ink from drying out. Because there was not much time left for me to try multiple prints and to think about the manual or bodily labor involved in printing lino or difficulties experienced in the process of it (which I thought was a pity).

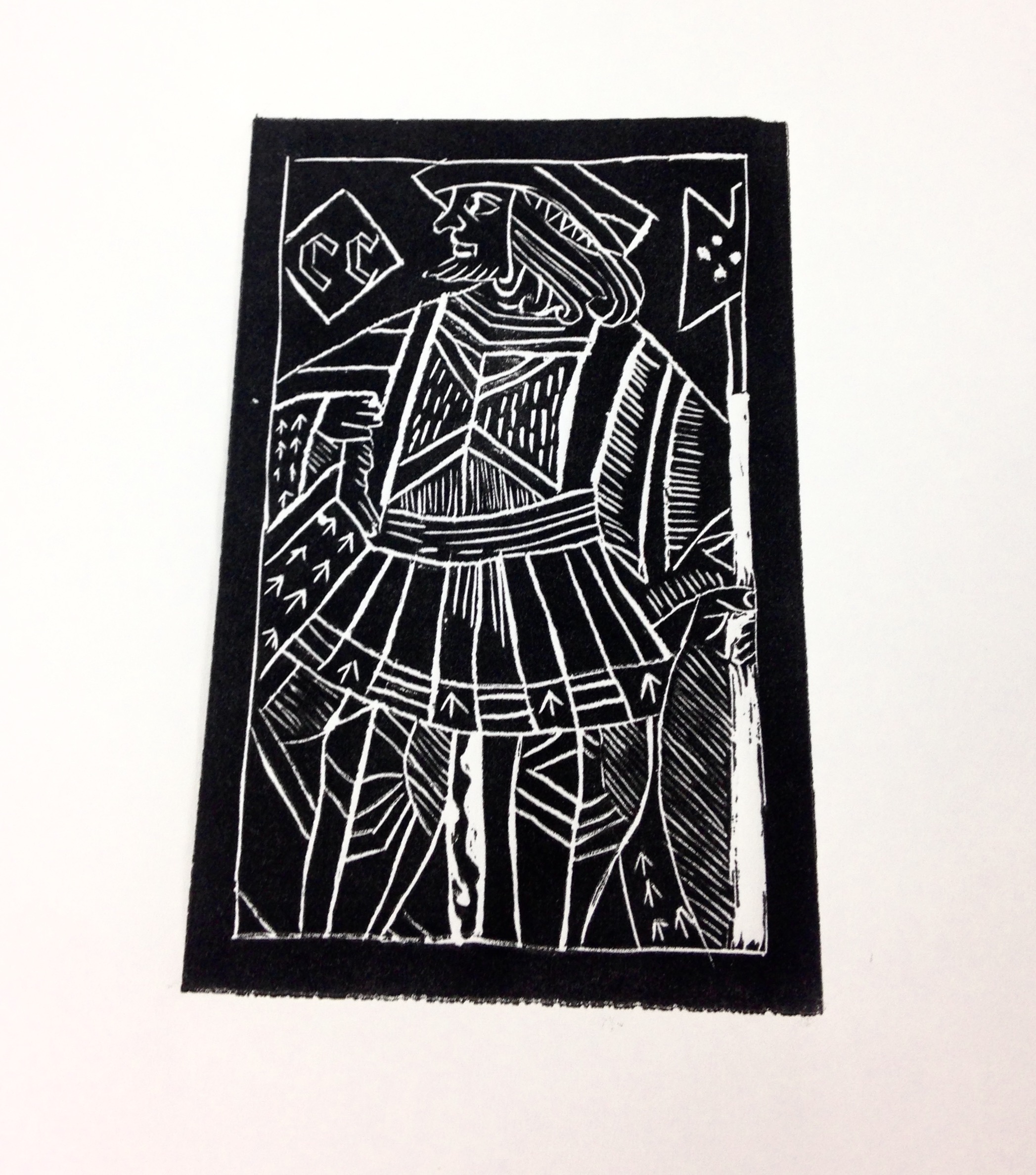

I was surprised to see that none of my hollows had in fact absorbed any ink -- especially given my initial concern the hollows were not deep enough.

It was also interesting to see a clear distinction of the lines (thick vs thin lines) -- something that was sometimes hard to see in the linoleum because of the low contrast between the hollows and the relieved areas.

Since there was little time left to print my linocut, Caroline told me she had forgotten to inform us that we should normally clean our linocuts before printing so as to remove remaining pieces of linoleum sticking in the grooves. We could therefore see that some of the incisions still contained remnants of linoleum that had set off ink onto the paper. A good thing to keep in mind for next time.

I would be curious to try another linocut without reversing black and white. It would also be interesting to experiment with different kinds of prints: very detailed vs. more ‘rough’ images, to play and familiarize myself with different techniques and how to use the gouging tool accordingly.

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Ad Stijnman, “Stradanus’ Printshop,” Print Quarterly, vol. 26 (2010), no. 1 (March), 11–29↩