Table of Contents

Dark red text has been formatted as certain heading types. To ensure the table of contents is rendered correctly, make sure any edits to these fields does not change their heading type. |

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Havemeyer Hall, Chandler 260, Columbia University, NY, NY 10027

Subject: Polish plate

Objective/Aim: becoming acquainted with various historical printmaking techniques: etching

The first step in learning how to etch was to clean our zinc plates (see image), removing all grease and stains, by polishing it with copper polish.

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Havemeyer Hall, Chandler 260, Columbia University, NY, NY 10027

Subject: Preparing the ground

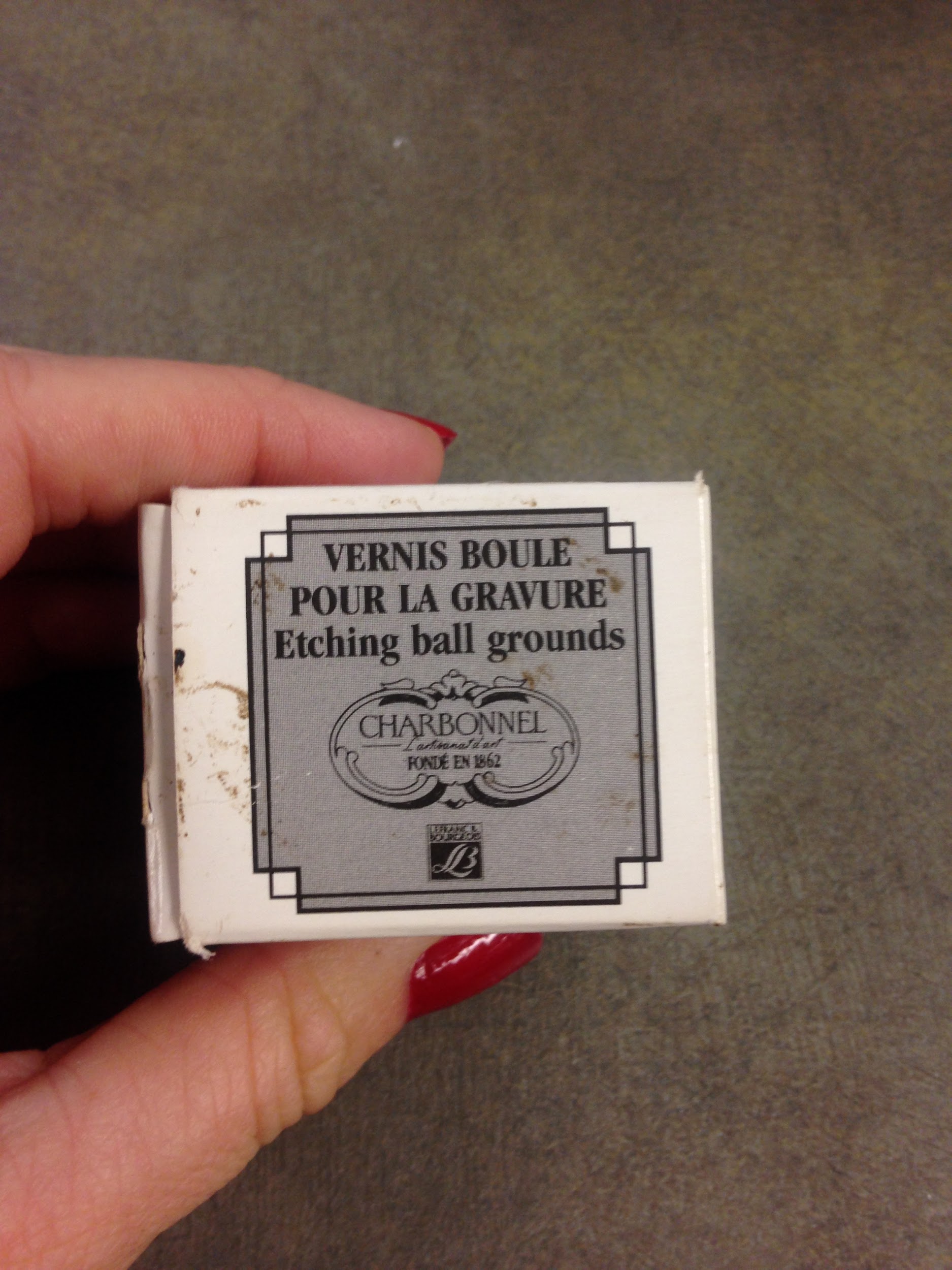

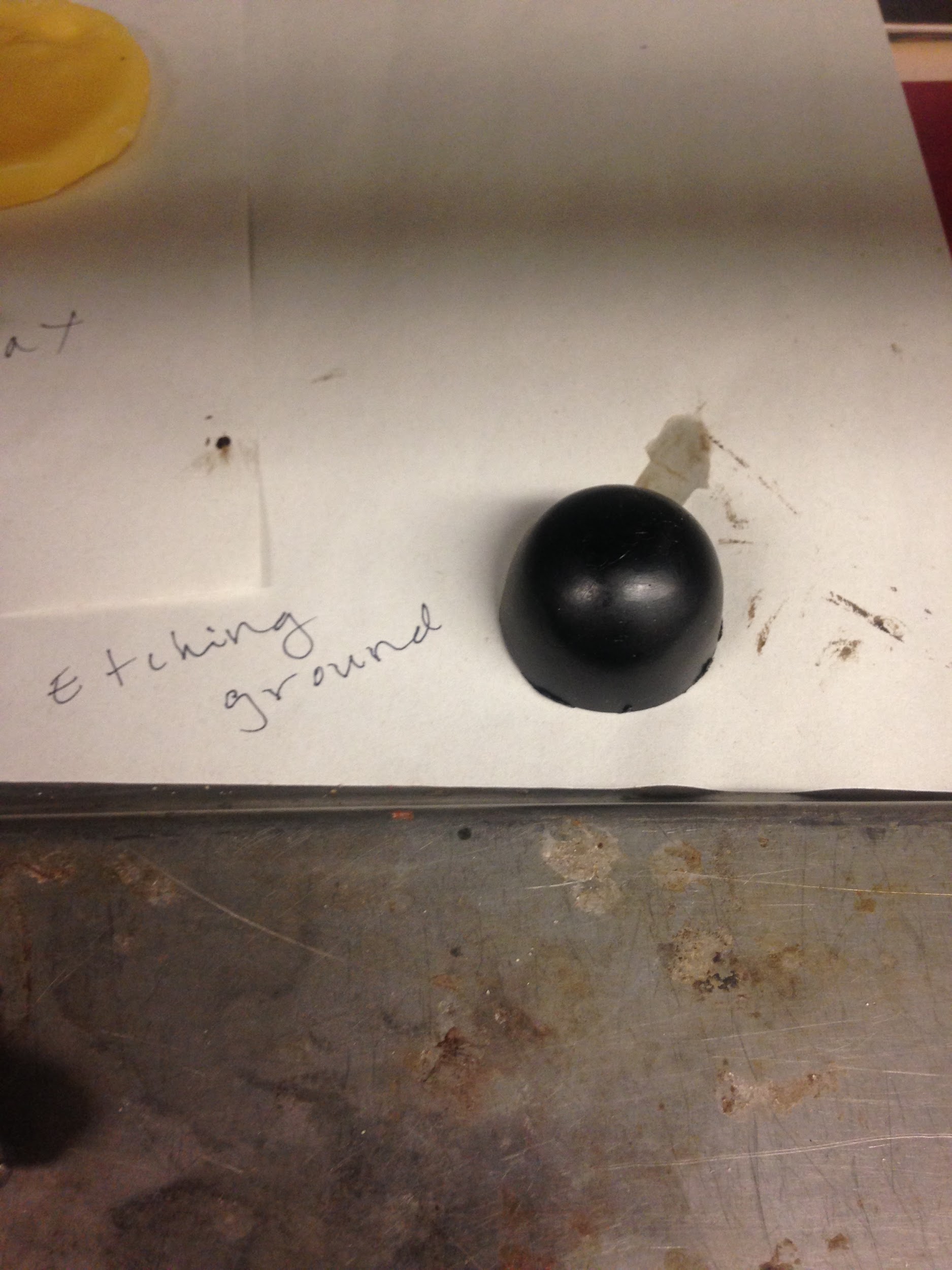

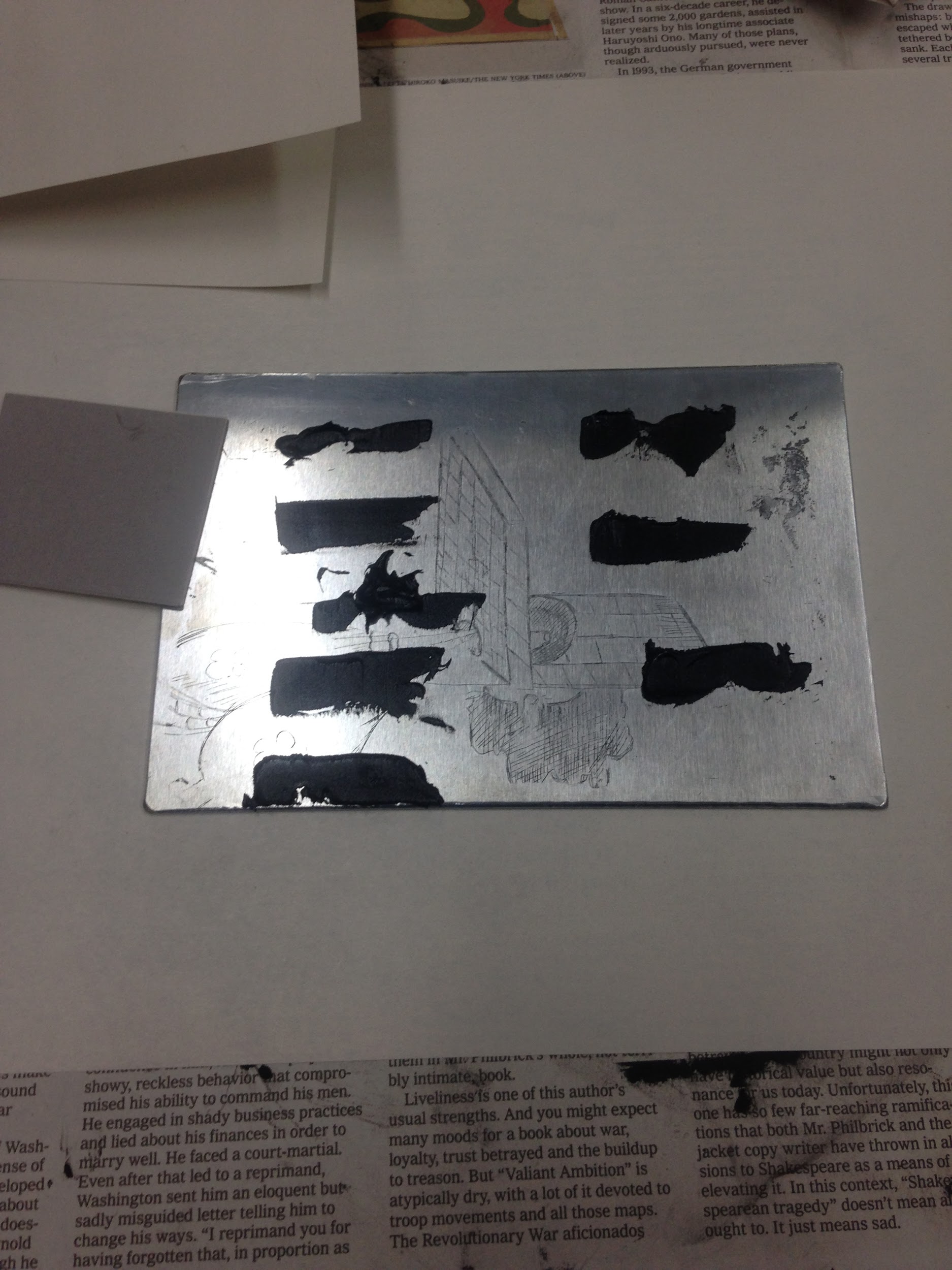

Next, we had to cover the plate with heated etching ground (see images 1 & 2).

In order to do so, I had to clamp my zinc plate in between pliers and rest atop a hot plate. That is, the zinc plate being about a finger’s height removed from the hot plate.

Once the plate and the ground are hot enough, the ground will melt and can be divided over the plate so as to cover it entirely -- by using a feather (see images 3-5).

N.B. use the curved side of the feather to divide the ground.

It took several attempts to do this, as it took awhile for the plate to be hot enough.

Once the plate was entirely covered in ground, we had to drop it on newspaper and let the ground cool off and dry (image 6)

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Private apartment, 405 West 118th Street, 10027 New York.

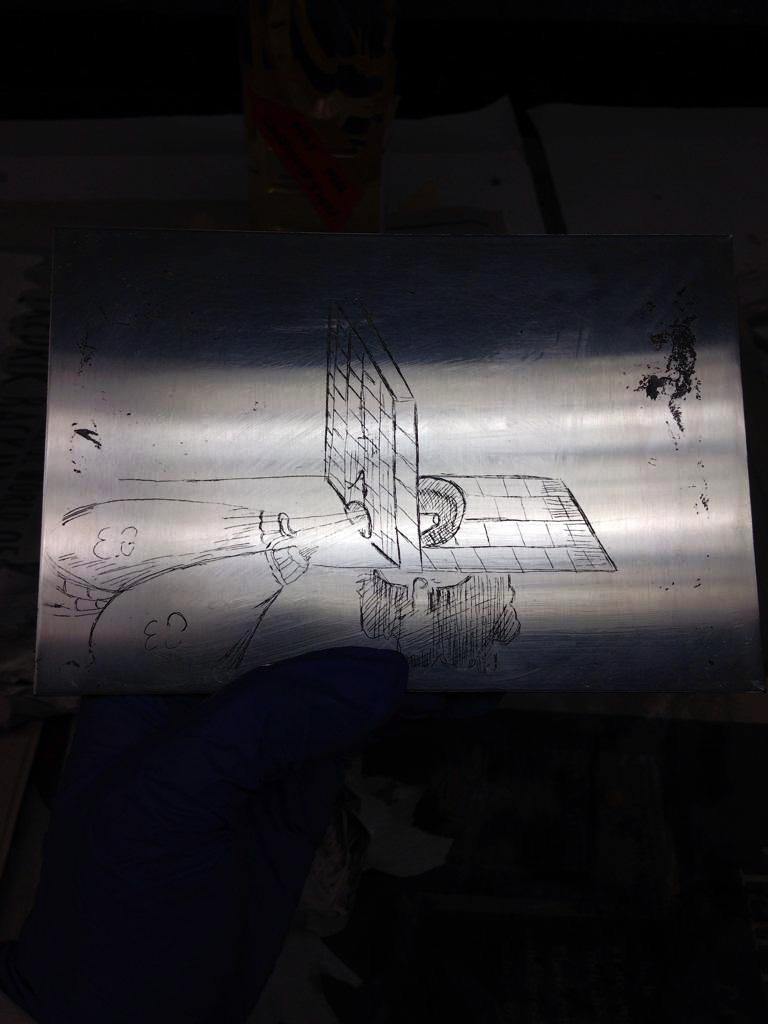

Subject: Transferring the design

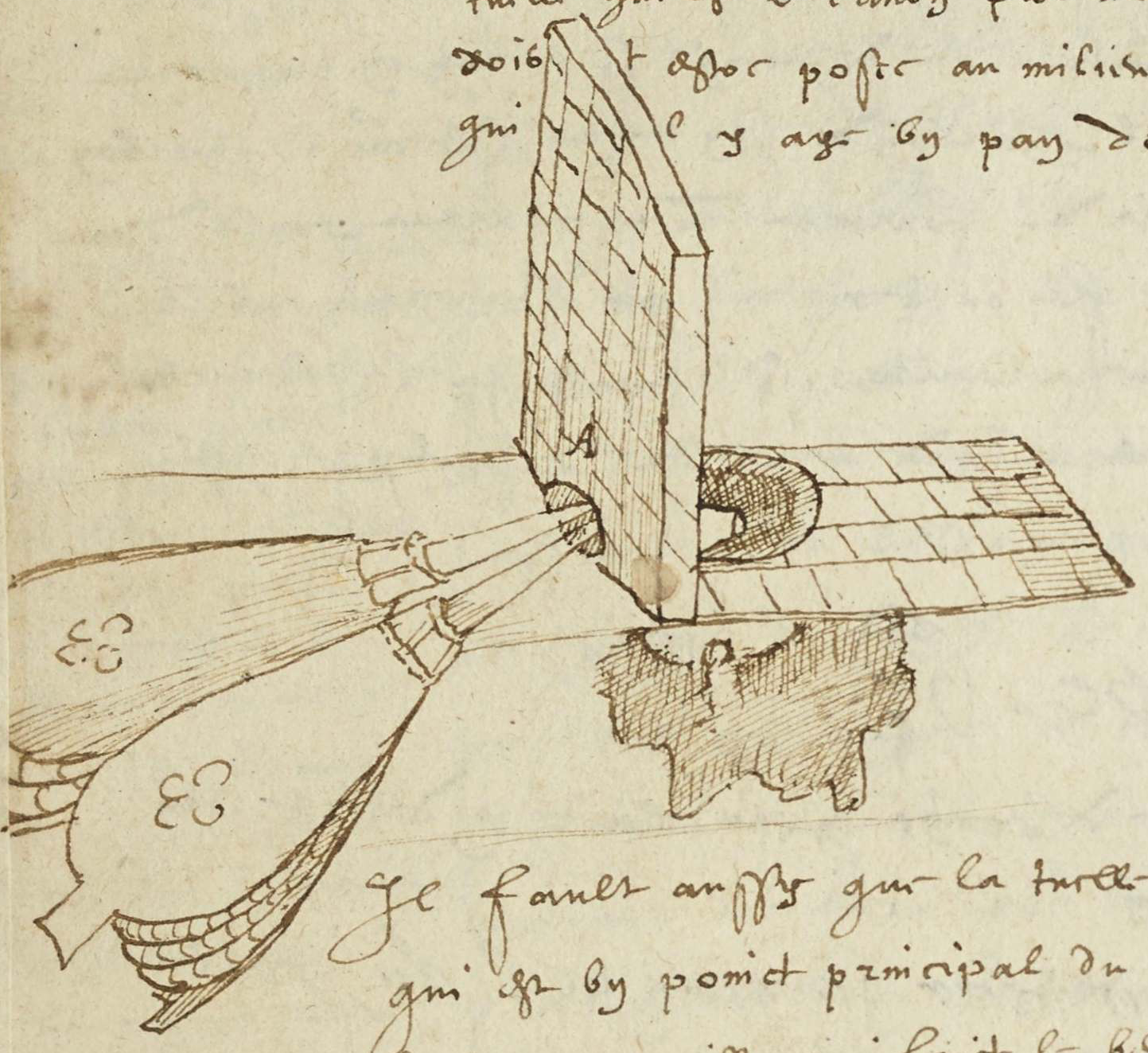

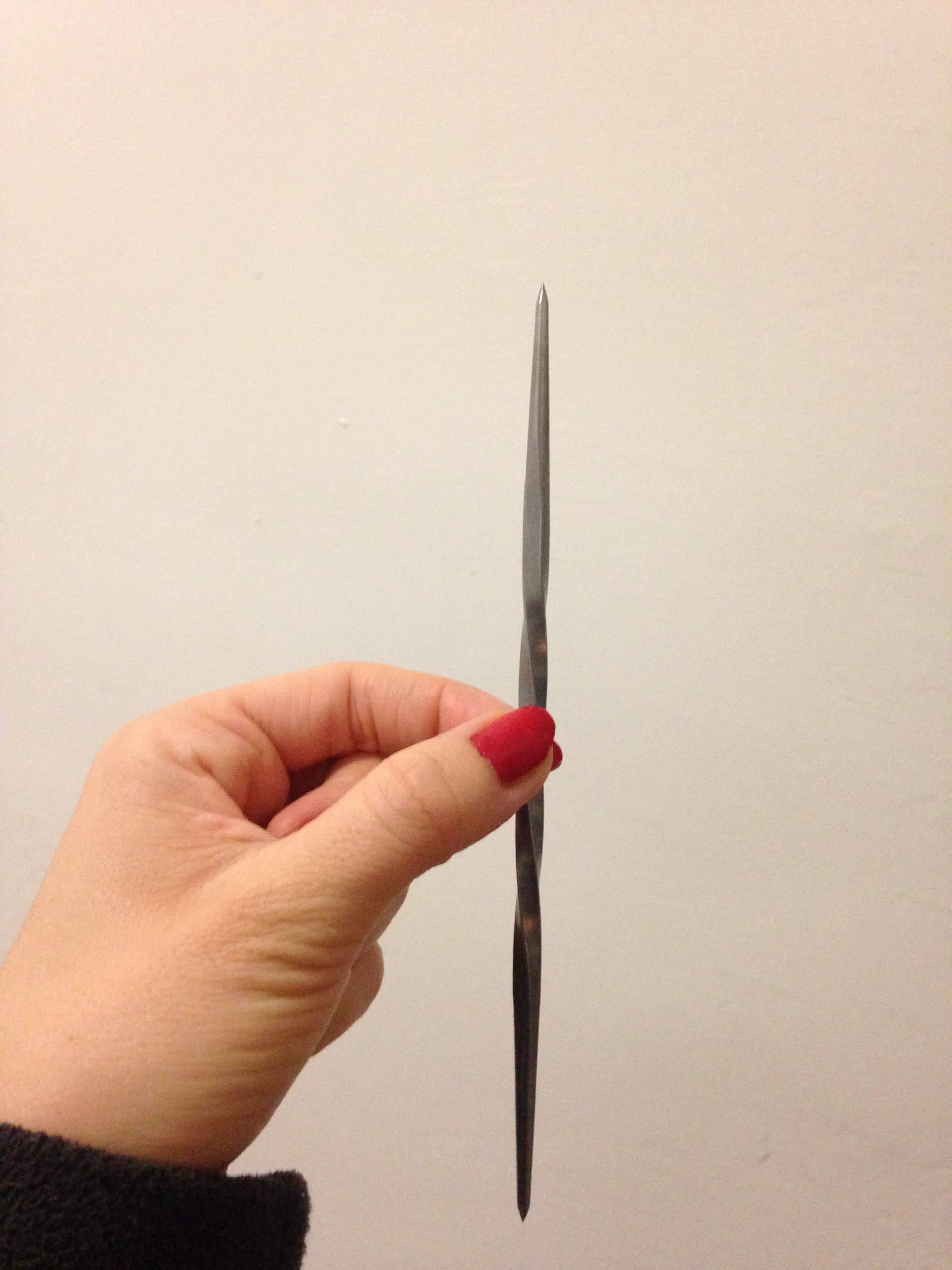

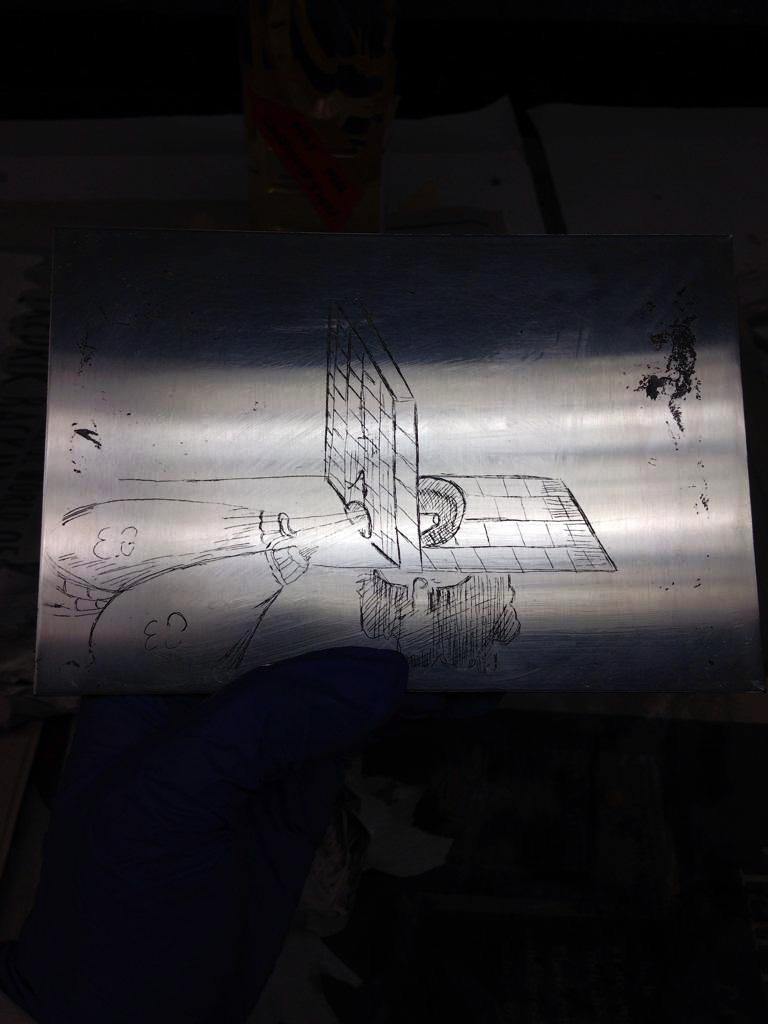

I would now have to use an etching needle (see image 2) to transfer my design onto the zinc plate, or rather carve gently through the wax.

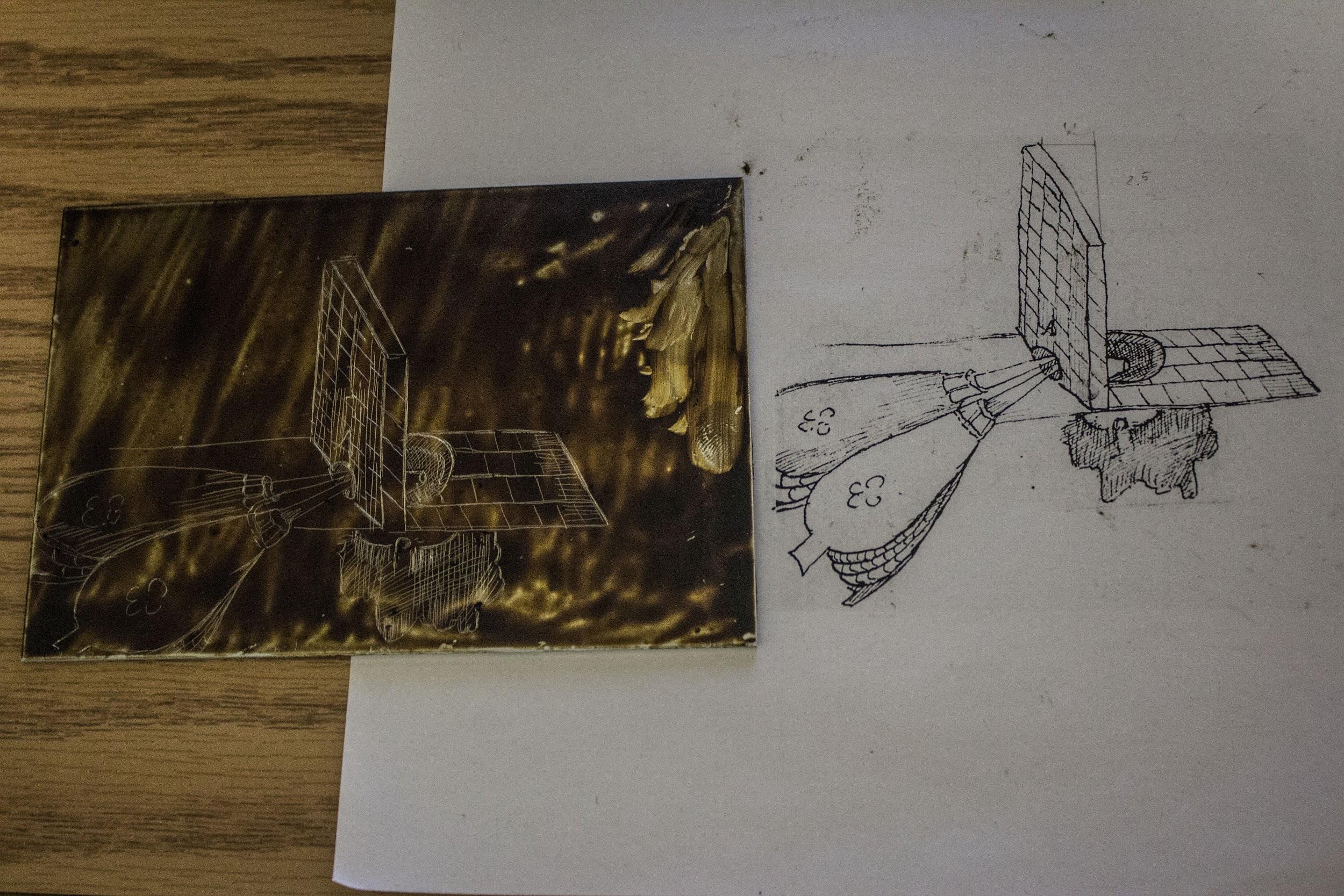

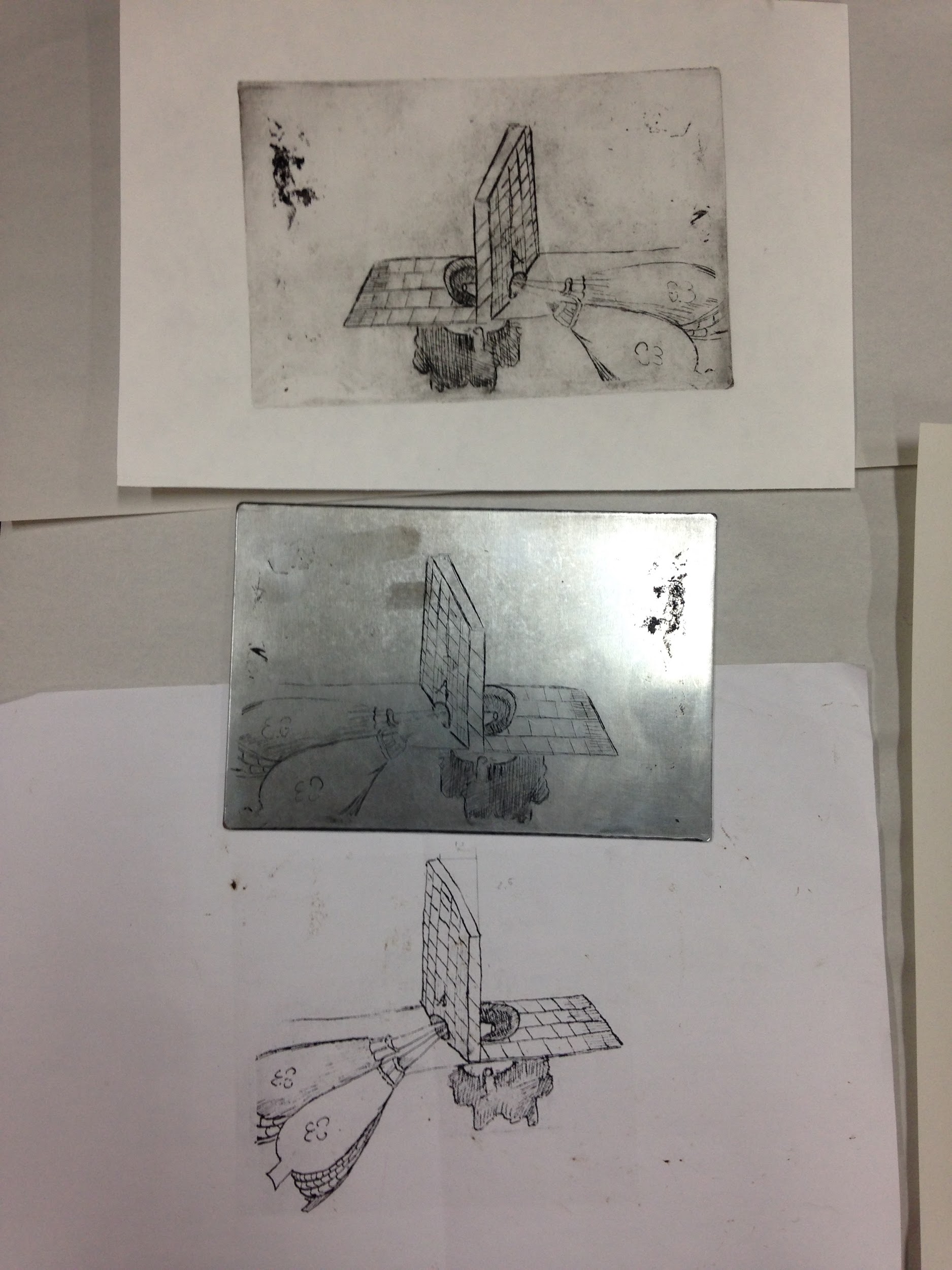

I had chosen an image from folio 16r (“Fonte de fer doux) of Ms. Fr. 6401 (see image 1). I was extremely curious to get an impression of what a figure from the manuscript would have looked like, had it been printed.

As I wasn’t aware that we could transfer the design by placing the image over the zinc place and trace the lines, I freehanded.

In retrospect I am very happy that I freehanded, even though it was more difficult and time consuming, as it made me aware of an interesting aspect of design transfer that I otherwise would not have thought of (see below).

I was surprised how easy it was to transfer the design onto the plate, or rather into the ground. The zinc lines were immediately visible, with very little effort or pressure. This was very different from lino cutting where more pressure needs to be applied in order to produce an incision or groove.

I had to clean the needle repeatedly as chunks of ground clung to it while I was pulling my needle over the plate to make an incision. This interfered somewhat with my ability to draw the design and to draw in a smooth manner. I suspect this was due to the ground not having been evenly spread over the plate. However, because I had become aware of the chunks being the problem, I drew more carefully and solved the issue by repeatedly cleaning the needle.

The perfectionist in me wanted to produce an exact replica of the original drawing and I therefore used a ruler to measure the length and width of each line to another. I realized very early on that this did not work and it was hampering me from actually drawing at all. So the ruler was put aside.

Most interestingly, freehanding made me aware of an interesting aspect of design transfer, that I could not have thought of if I had merely traced a set of line and shapes on a piece of paper.

As I am only just starting to think this through (while writing) and am still trying to find the right words to express my point, I hope I can communicate my thoughts clearly:

If you look at the original ink drawing, you can see a stain-like spot at the center-bottom margin of the figure, right underneath the wall. In the middle of that ‘spot’ is a figure that I initially took to be a conjunction of lines collectively forming a ‘P-shaped’ figure.

Because I initially recognized nothing in this set of lines, other than they resembled a P, I was transferring every single line that this shape was comprised by moving back and forth between the original and the etched plate. That is, I looked closely at the original length, width and shape of each of the lines forming a P, and then, after having studied it, tried copying it over onto my etched plate. This required a lot of hand-eye coordination as the two could not be done in tandem (tracing the lines on paper would have been so much easier).

However, it was only later, after I transferred the entire image of fol. 16r onto my zinc plate, that I realized the figure in question might in fact not be a random placement of lines resembling a P, but rather could be a pipe.

I thus went back to my zinc plate and redrew the image. This time not by oscillating between the original and the etch, but rather by drawing upon my own visual memory, understanding and conceptualisation of what a pipe normally looks like. It was thus my (possibly erroneous) identifying of that shape as a pipe that changed the manner in which I was transferring the design. My ability to rely upon my own existing mental imageries (or visualisations) of pipes allowed me to draw much more freely.

My hands were ‘translating’ those mental images into a bodily movement and thus onto paper.

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

I realised that good lighting is essential in order to see where you’re are drawing a line. The lighting in my apartment wasn’t bright enough and I had trouble seeing whether or not I have already drawn a line on the surface or not.

When about ¾ of my design was done, I realised all of my lines were of even width and depth. However, the lines of the original were not. I wasn’t sure if, in order to create darker lines, I would have to make deeper incisions, or had to carve multiple narrow lines next to each other. I decided to carve into existing lines a bit more, hoping that this would create darker lines in the printing process.

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Havemeyer Hall, Chandler 260, Columbia University, NY, NY 10027

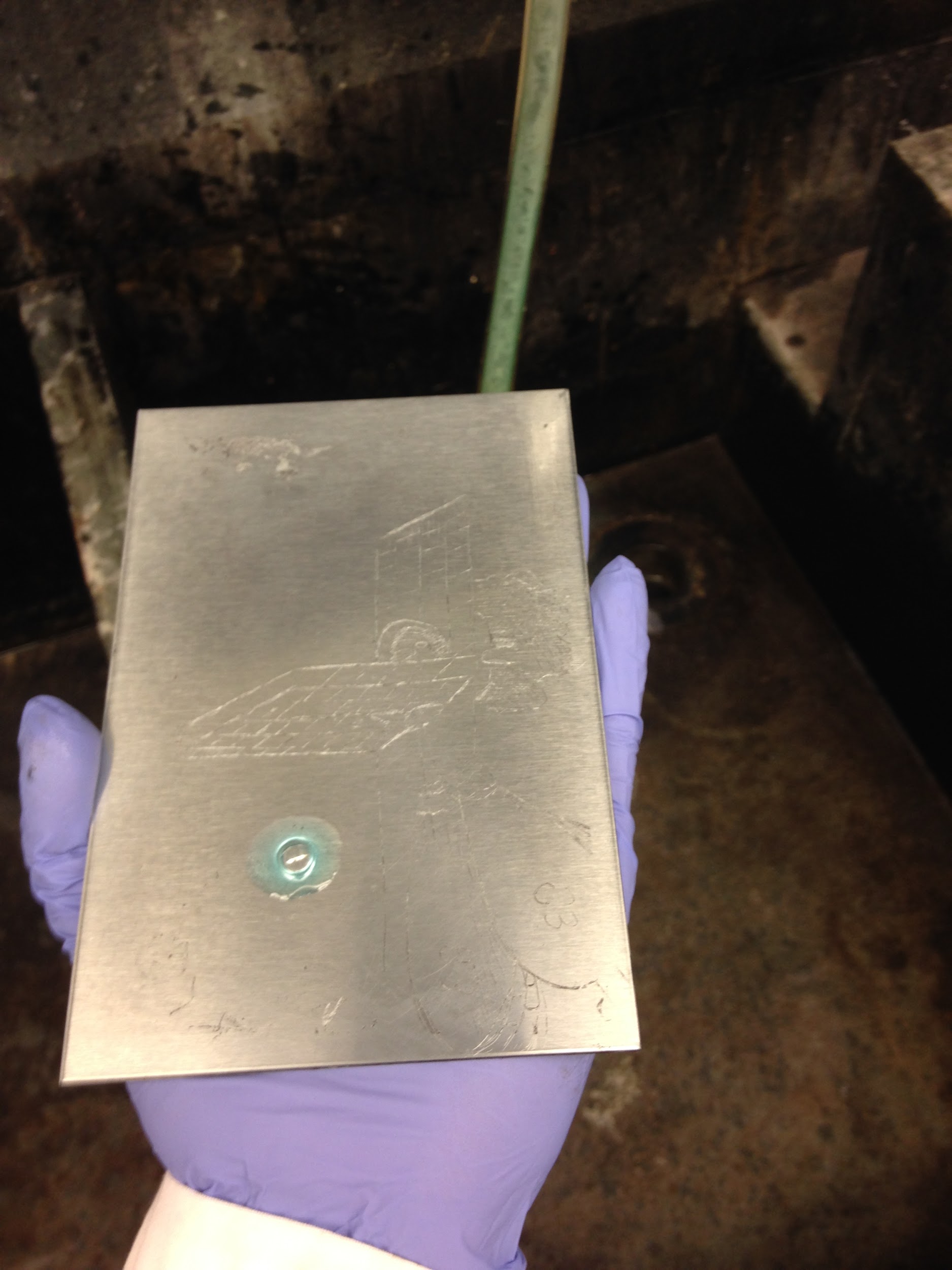

Subject: Taping the plate

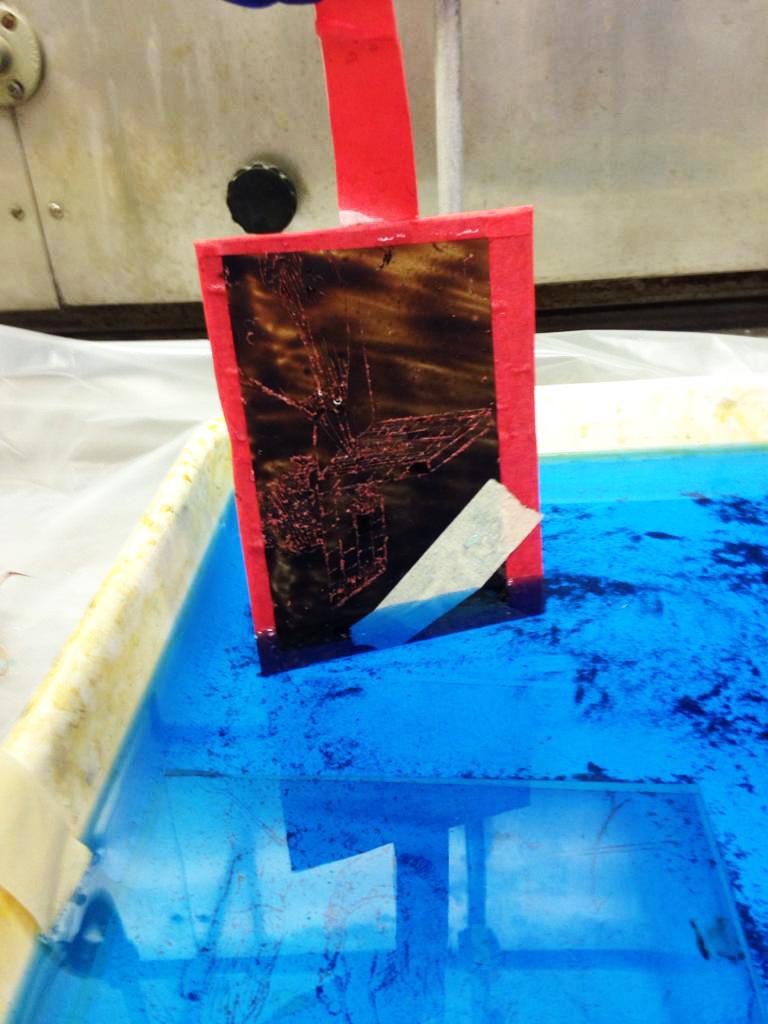

Before starting our ‘bathing’ of the plate, we would have to cover the sides and edges of the plate with tape to prevent foul biting, which could ruin our design (see image 2).

Additionally, we had to make a handle to lower and lift the plate out of the sulfate (see image 2)

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Havemeyer Hall, Chandler 260, Columbia University, NY, NY 10027

Subject: ‘Bathing’ the plate

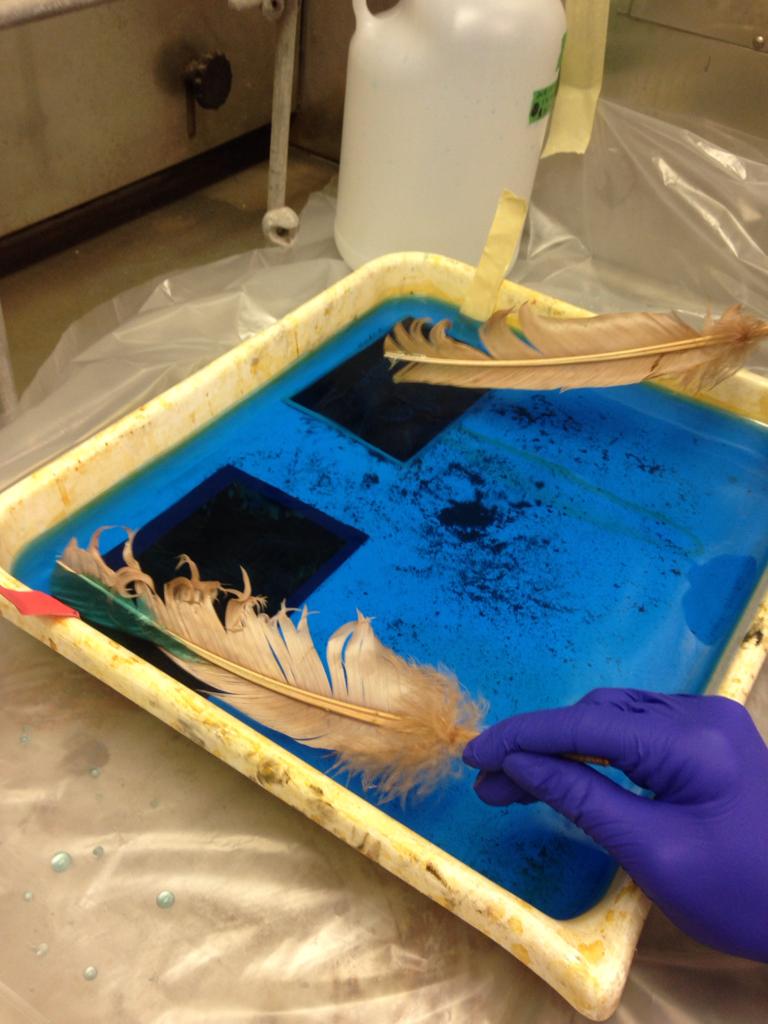

To hollow/etch out the grooves, we would have to place our plates into a bath of (blue) copper sulphate placed in the fume hood (see image 1).

We could lower the plate gently into the bath with our self-created handle.

Then use a feather to keep the etched out copper (or sediment) from settling in the grooves (and thus keep them moving). This could be done by gently brushing over the plate (barely touching it).

Ad advised me to be extremely cautious with this as I had used a very soft ground.

We could decide for ourselves how long we would leave our plates in for. Depending on how deep and wide we wanted our grooves to be.

Not long after I had placed the plate into the bath, I saw the grooves turn red (see image 2) An amazing effect to see! I could see the design very clearly now.

I took it out after 5 minutes as I was concerned it would widen my grooves too much.

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Havemeyer Hall, Chandler 260, Columbia University, NY, NY 10027

Subject: Rinsing the plate

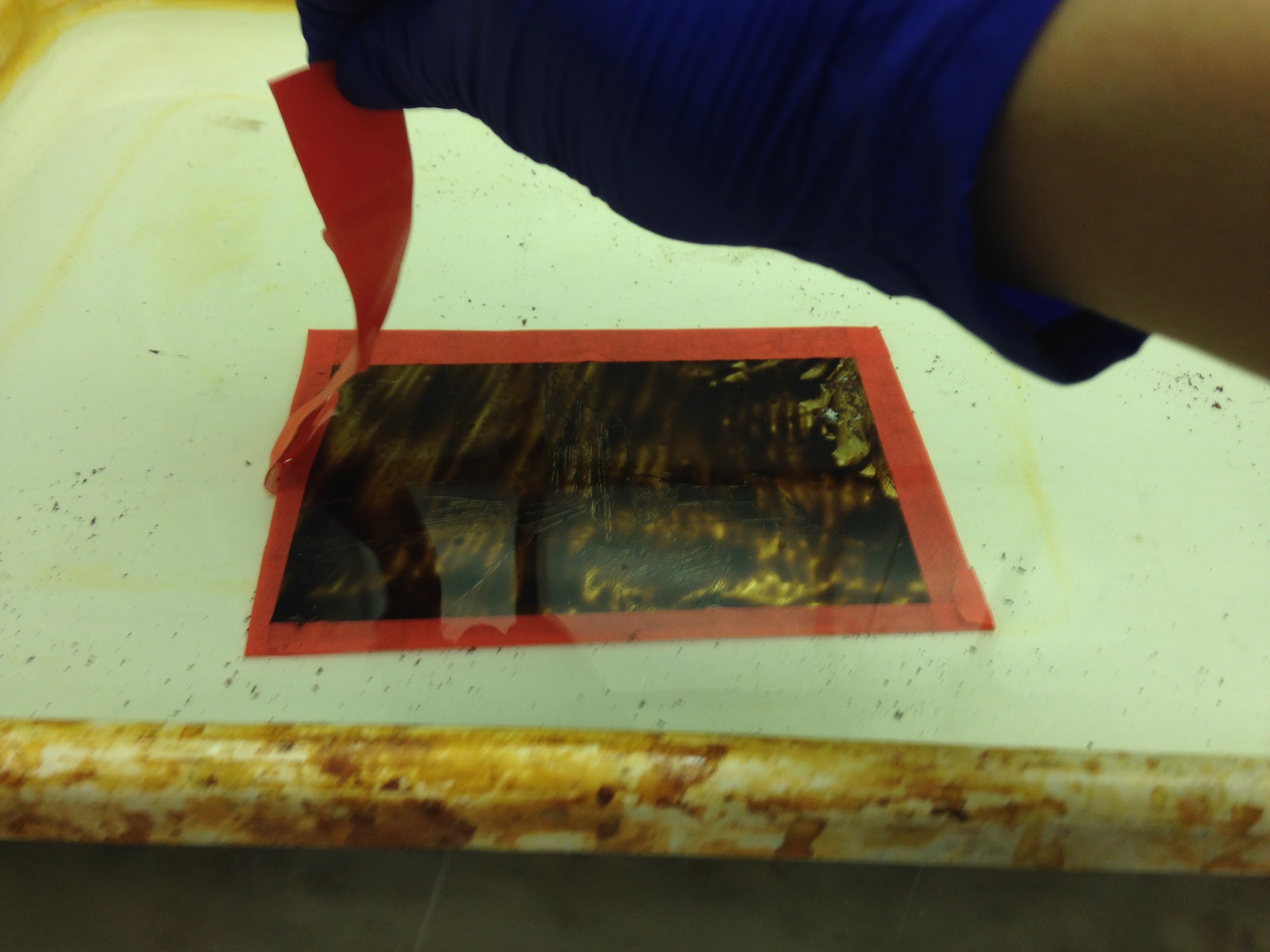

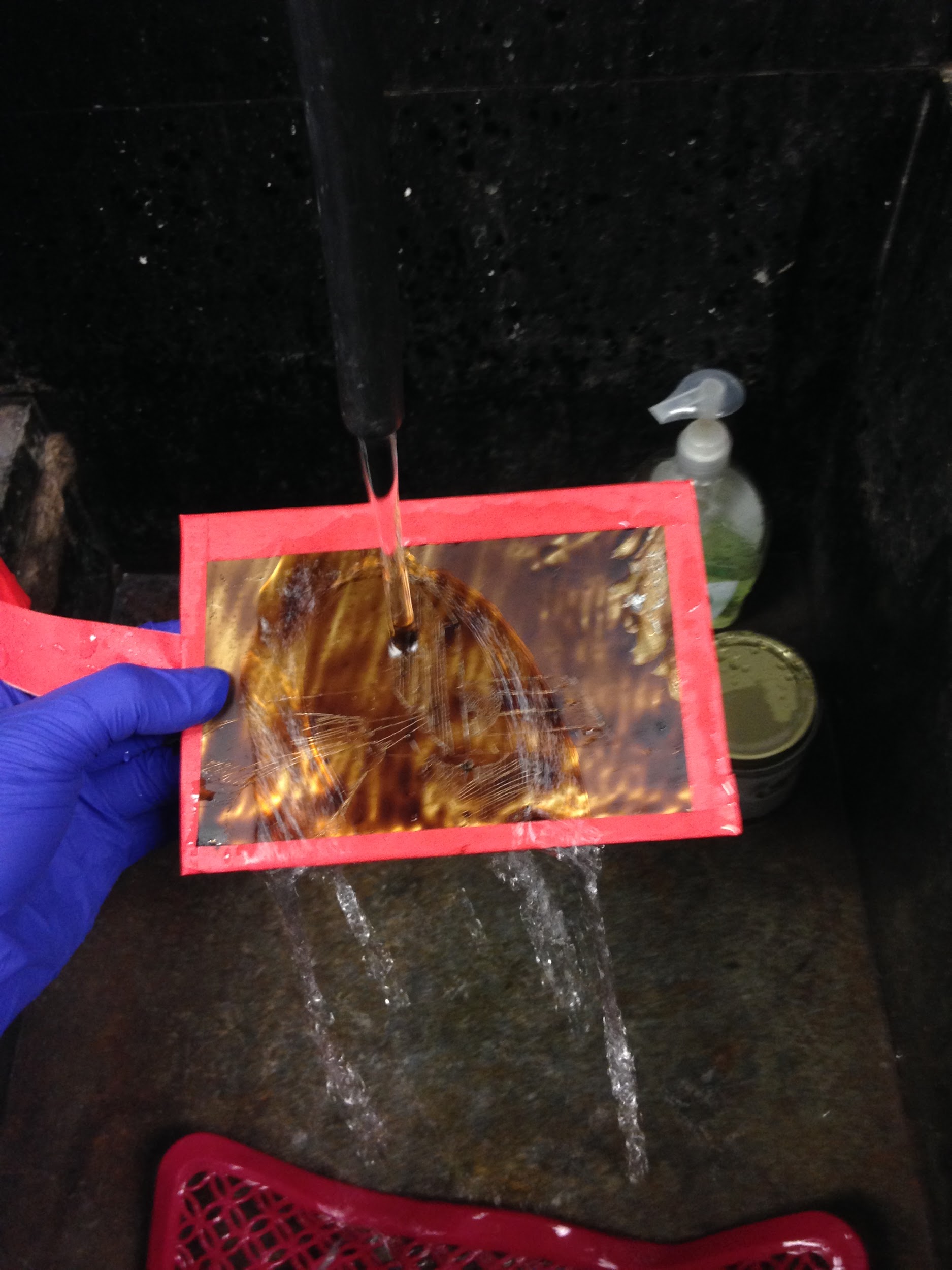

The next step was to put put the plate straight into the rinsing bath (filled with plain water).

In order to remove the copper residue we had to move our plate by pulling it from side to side in the bath for a few seconds (image 1).

Then take it out of the bath, place it on a plate and move it over to the sink, where we would have to rinse it thoroughly by holding it under running water; removing all copper residue (see image 2). This meant no red spots should be visible anymore. I used my fingertips to gently rub over the grooves to help remove the copper sitting in the grooves.

When done, gently dab the plate dry with a piece of paper (image 3)

I wasn’t sure if I had left my copper plate in long enough as I could barely feel or see any grooves. I thus decided I would put it in another bath.

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Havemeyer Hall, Chandler 260, Columbia University, NY, NY 10027

Subject: ‘Bathing’ and rinsing the plate - round 2

Because I didn’t believe the grooves were hollow enough, I decided to give my zinc plate another bath. This time I left it in for 15 minutes (making a total of 20 minutes).

I took the plate out of the etching bath and placed it into the rinsing bath. When I took it out, you could see drops having settled into the grooves (see image 1). I then rinsed the plate thoroughly again with running water.

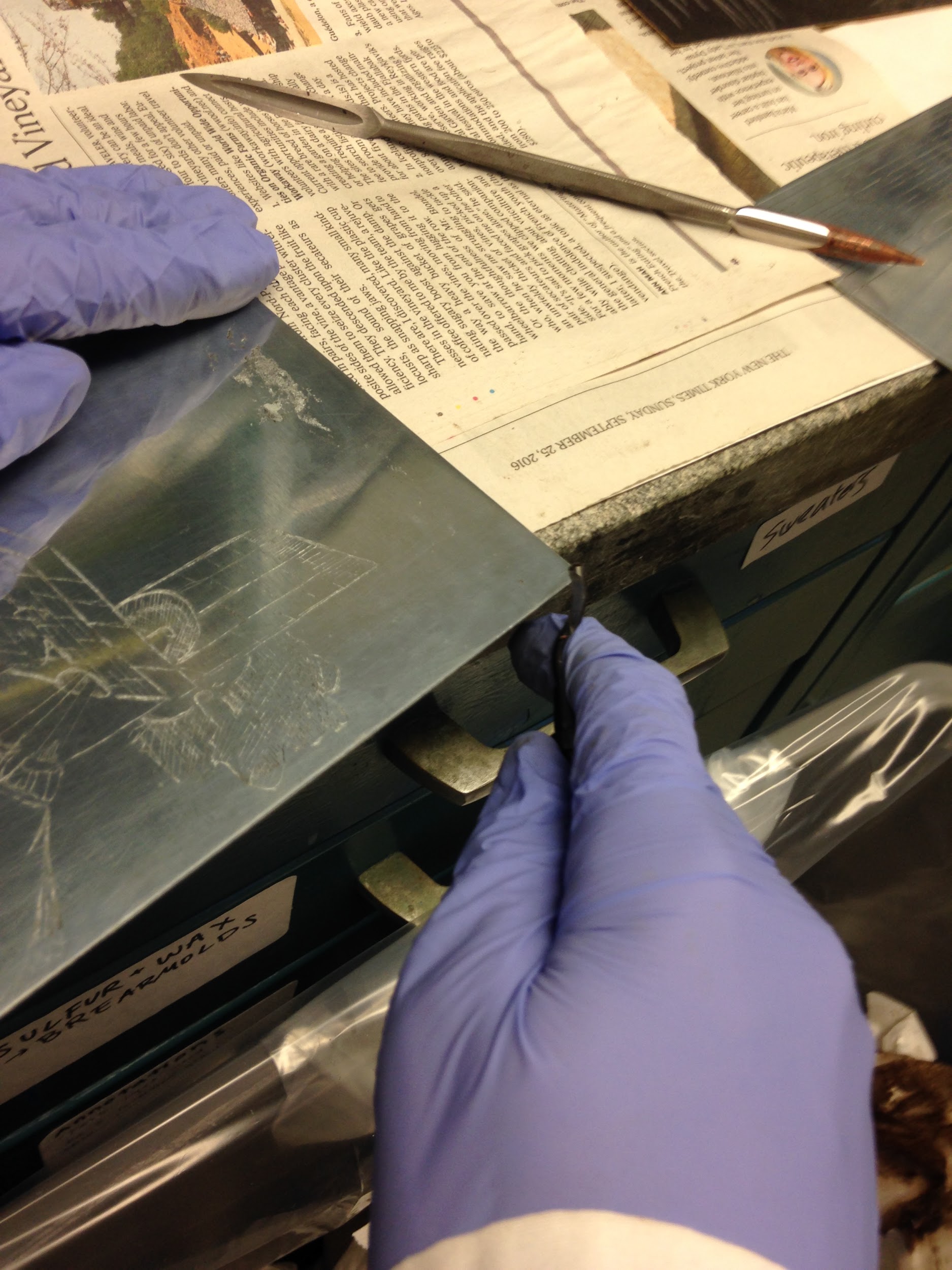

After having rinsed the plate properly, Ad advised me to use an etching needle to stick into the grooves to see if they were ‘deep’ enough (see image 2). I thought they would be ok (Ad confirmed they would definitely print).

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Havemeyer Hall, Chandler 260, Columbia University, NY, NY 10027

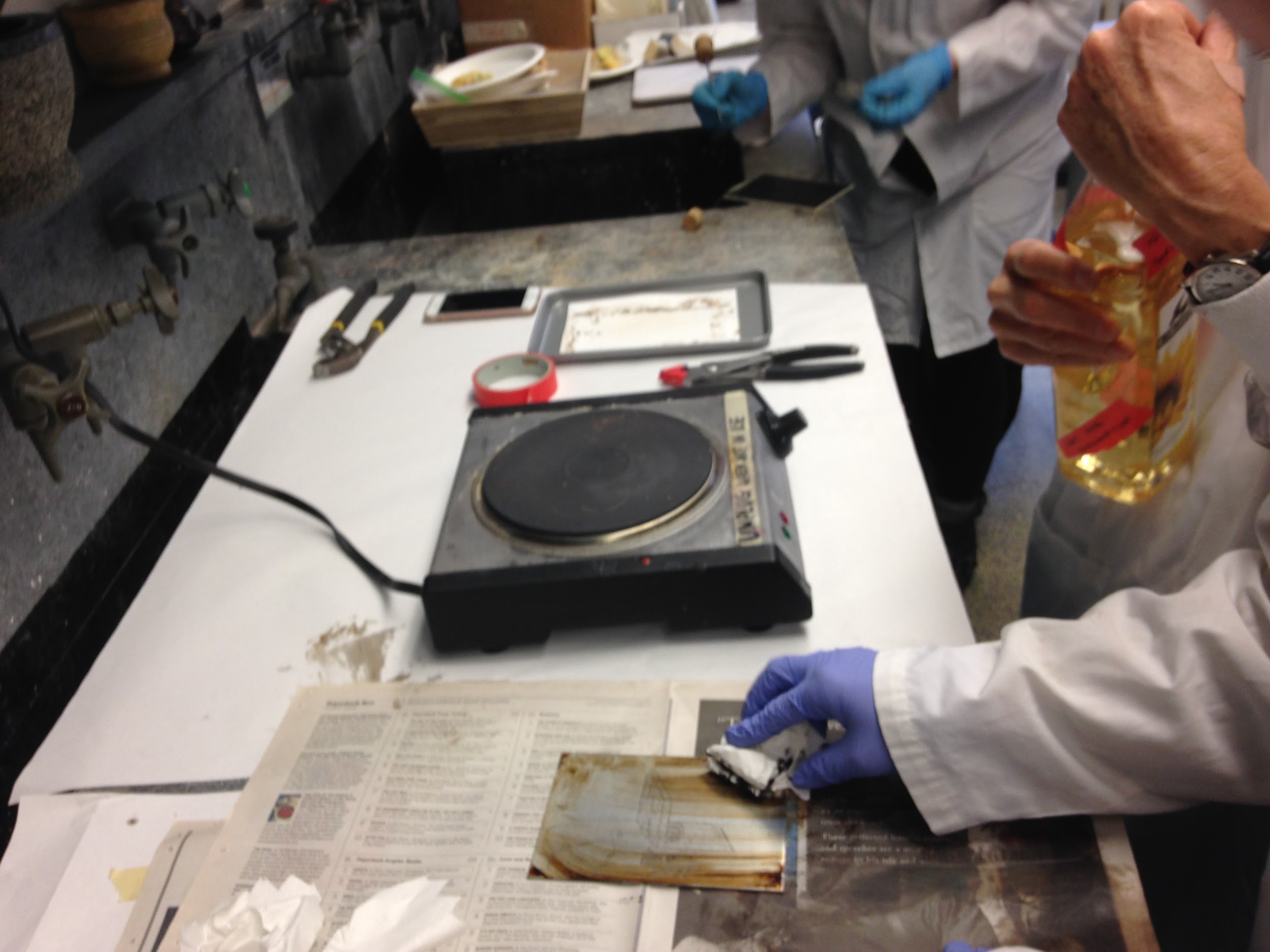

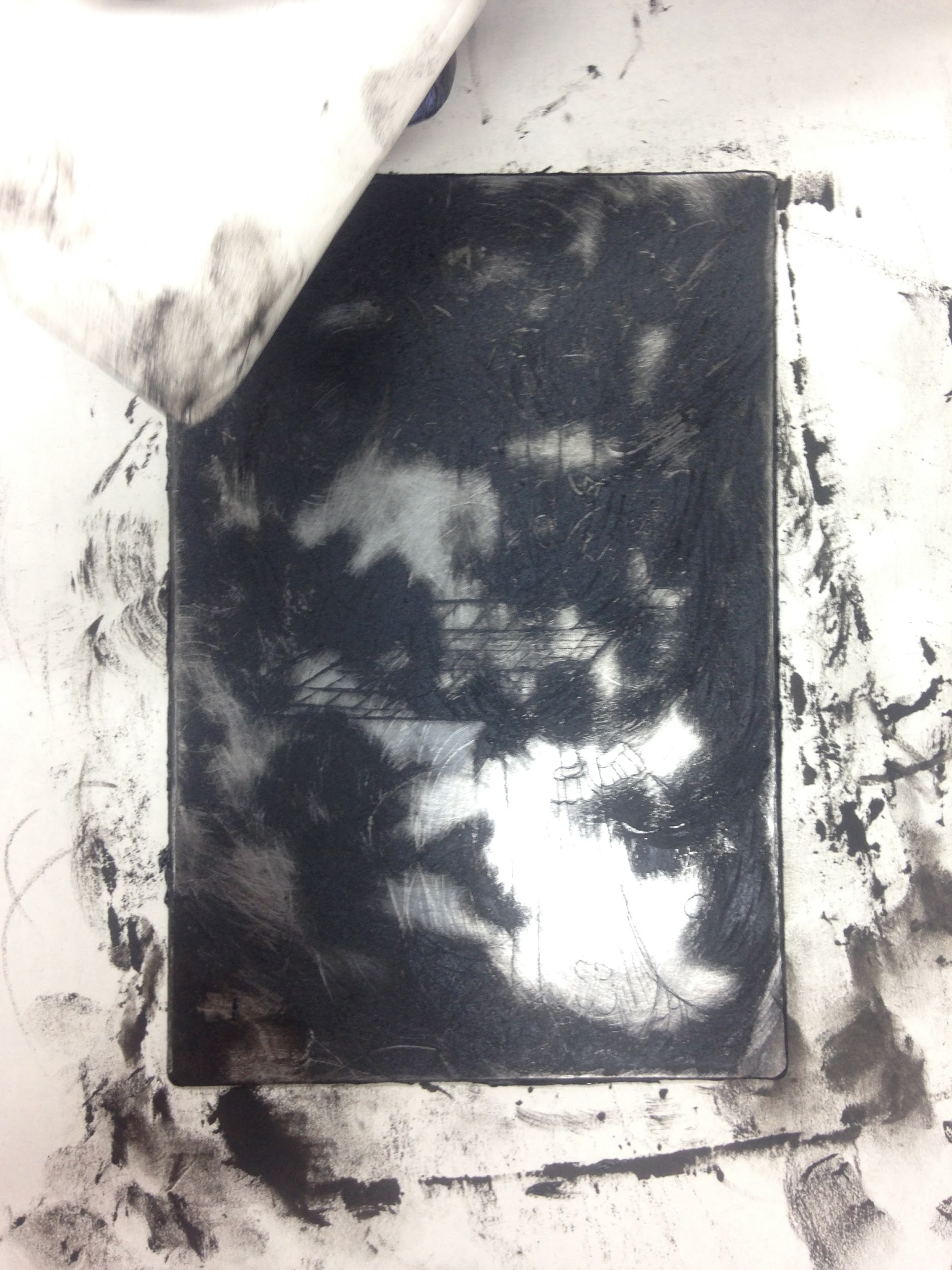

Subject: Removing the ground, cleaning the plate

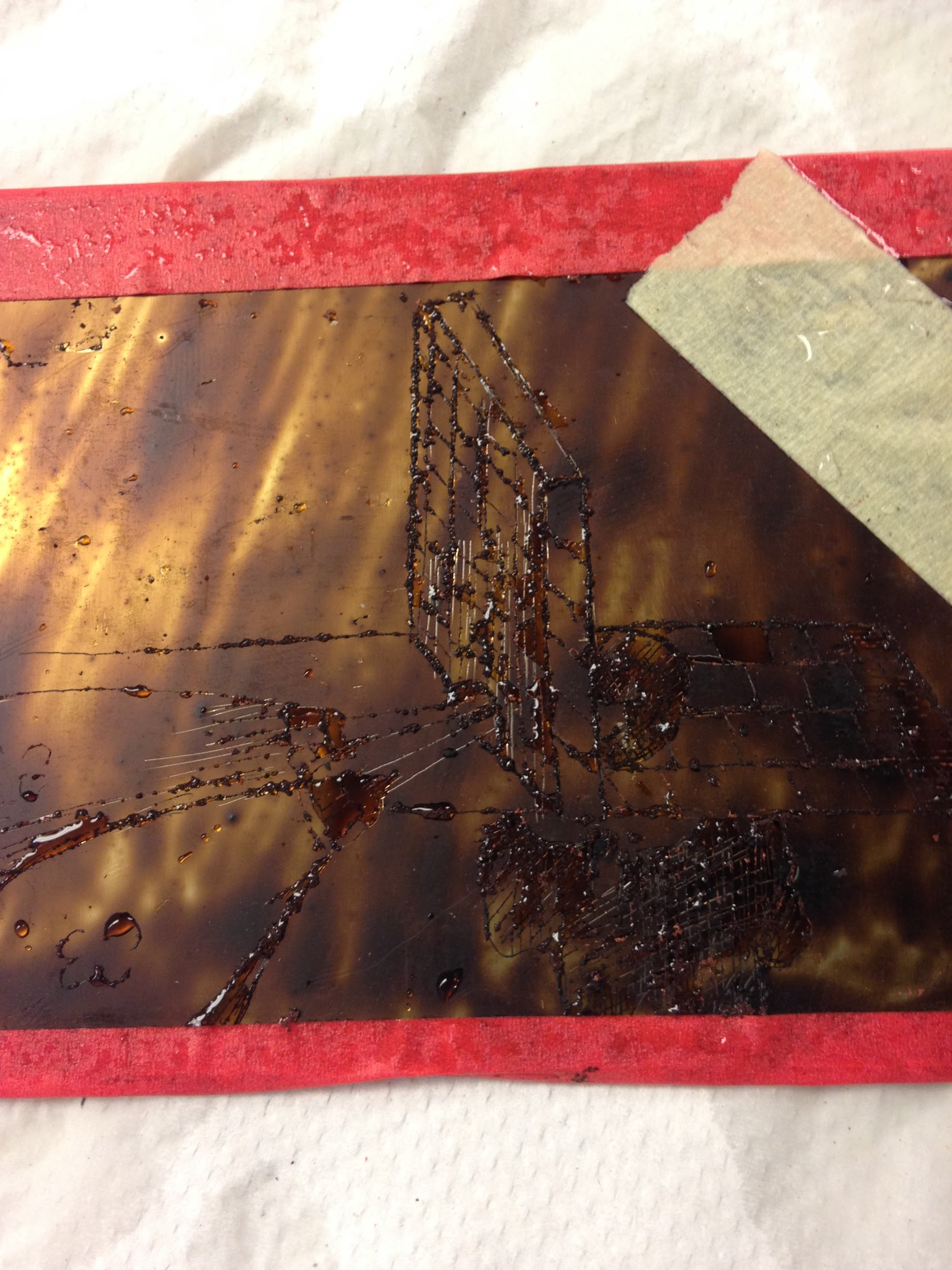

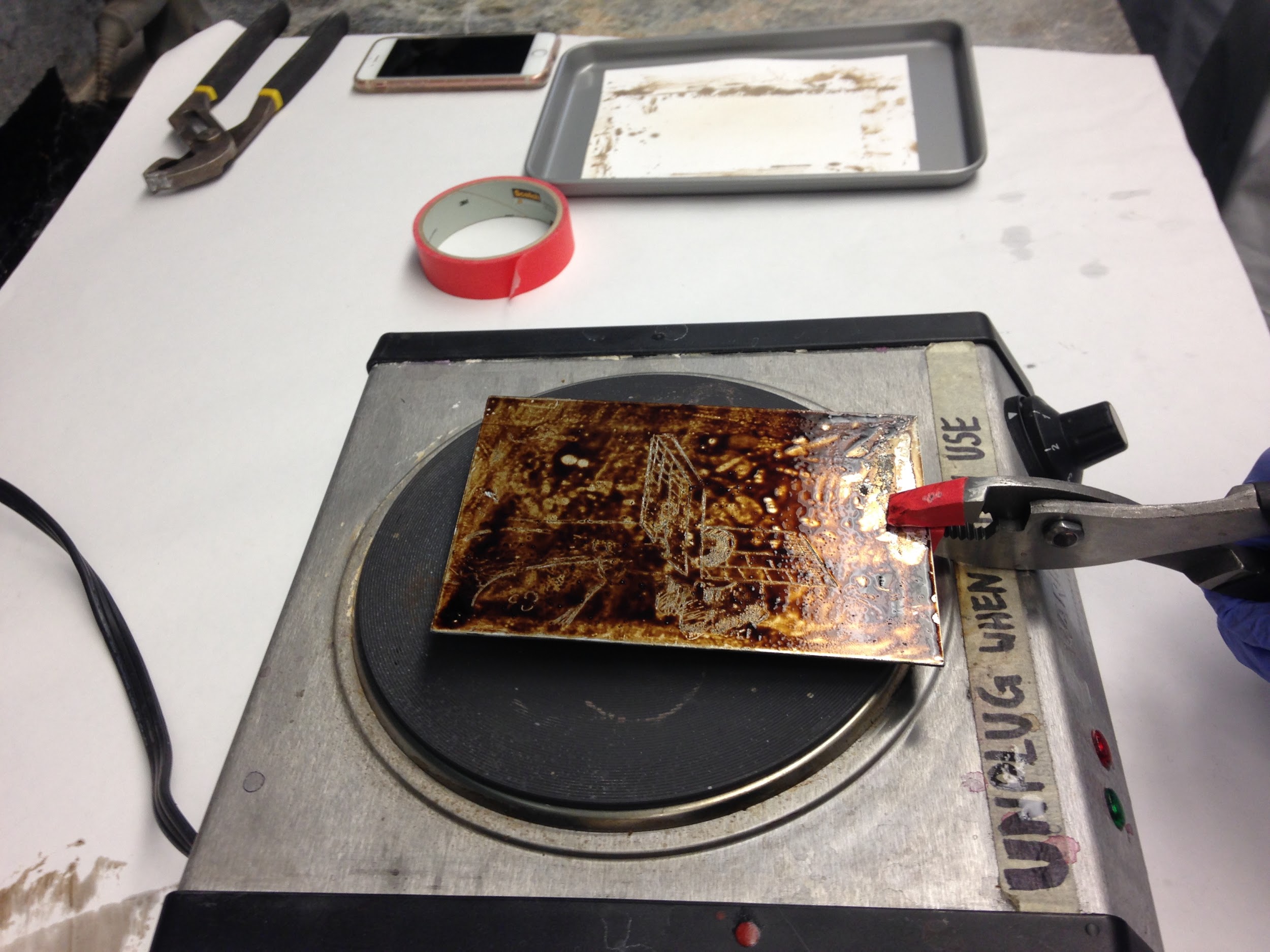

The next step was to heat the zinc sheet by holding it with pliers above a hot plate -- it was helpful to rest the pliers on top of the hot plate, so as to not put too much pressure on your arm. This would allow the ground to melt and enable us to remove it easily.

It was very exciting to see that the etched grooves were more visible once the ground

become soft and liquid than when the plate had just come out of the rinse bath.

Something I had not anticipated (in fact I was worried I should have left it in the etching

solution longer).

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

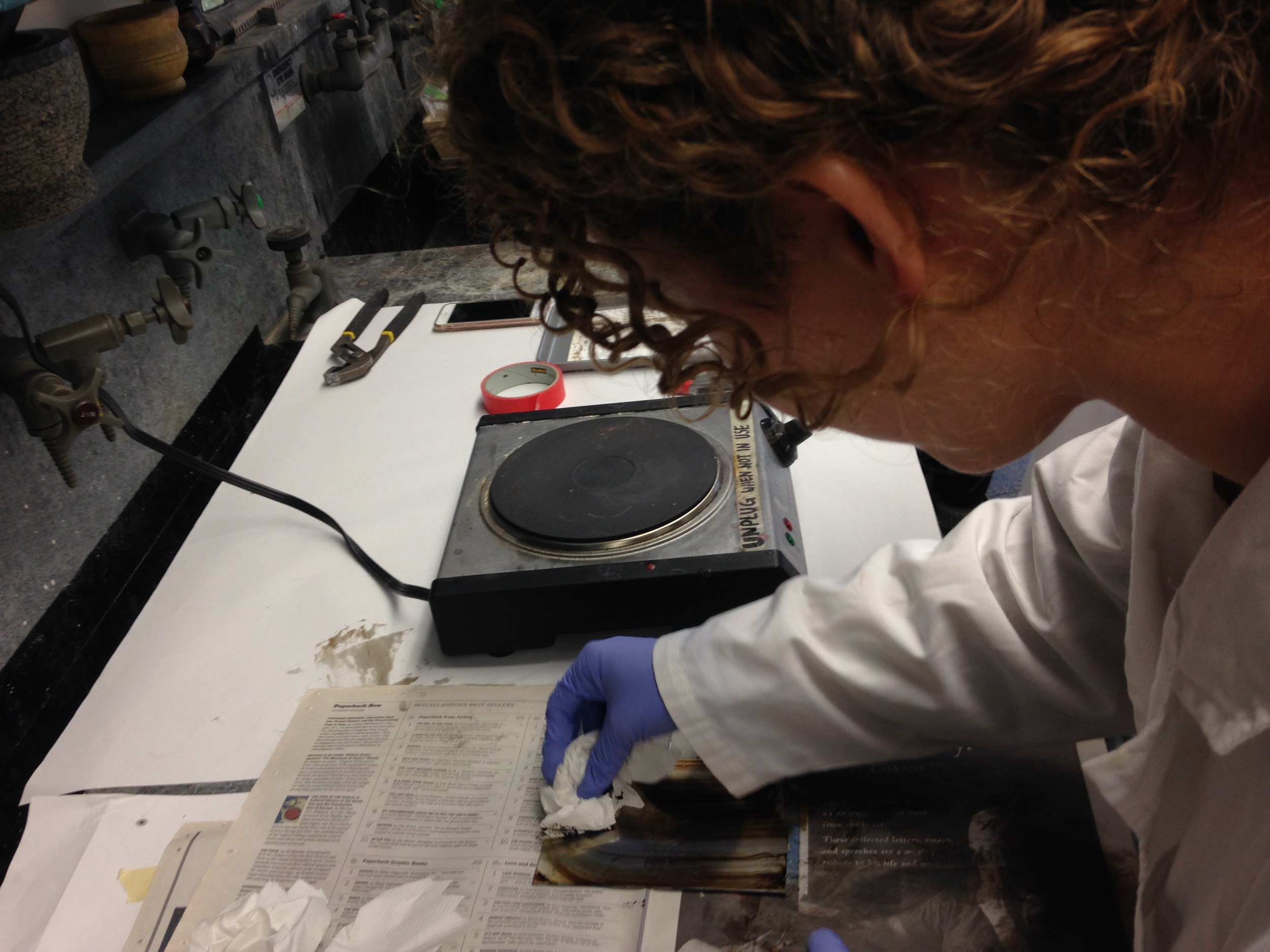

Once the ground was liquid enough (it became shiny), I had to use paper towels to remove the ground. After having removed the majority of the ground, I had to pour a little bit of oil on the plate, to remove the remaining ground.

It was important to act swiftly and to use the oil only when the plate was still hot.

Then I rinsed and cleaned the plate with water and soap.

I was amazed to see how clear you could now see the design and I was very curious to

see if the grooves were deep enough for any ink to sit in (and to offset a distinct image

onto paper).

Aside from a few foul-bitings on the margins of the plate (which the perfectionist in me hated), the design looked amazing and I couldn’t wait to see the result.

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Havemeyer Hall, Chandler 260, Columbia University, NY, NY 10027

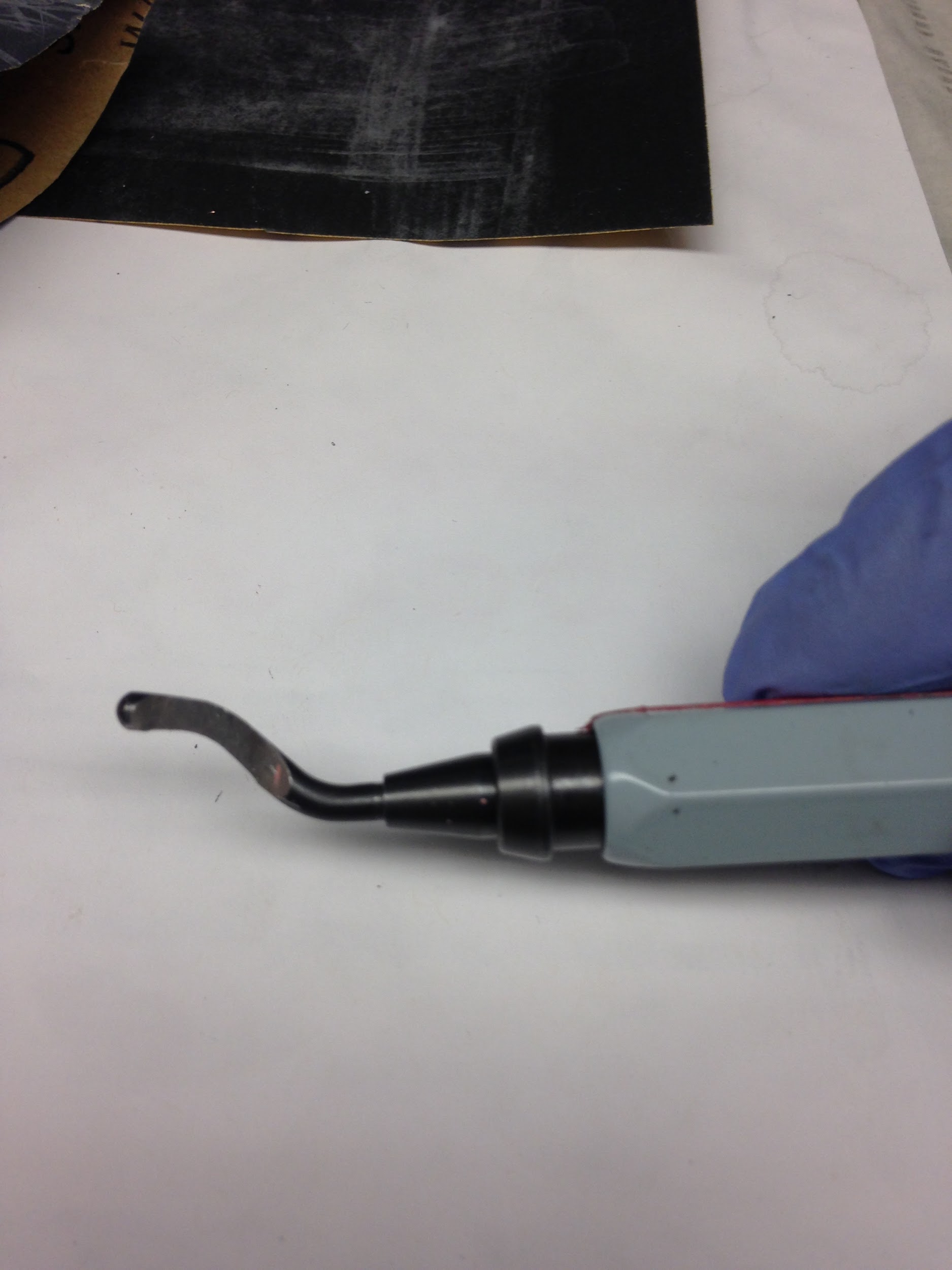

Subject: Beveling and softening the sides and edges

Next step: bevelling and softening the edges of the sheet to prevent them from damaging the paper when printing.

We used a bevelling tool (see image 1) with a curved tip to do this. The aim was to

remove strips of curled zinc from the edges to soften them. It took a while to find the

proper angle at which to hold and pull the tool towards me. Once I had succeeded in

creating a curled iron filing, it was a rather automatic process.

This was fun!

I found it rather difficult to determine what would be soft enough and I checked with both

my fellow students as well as with our expert maker Ad Stijnman. There was no way to

fully guarantee that the edges would not damage the paper -- trial and error as usual.

After having softened the sides and edges of the zinc plate with the beveling tool, we had to use sandpaper (1200) to level them and make sure there were no bumps or burrs.

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Teachers College, 525 W 120th St, New York, NY 10027

Subject: Beveling and softening the sides and edges

After Ad had explained to us the step-by-step process of intaglio printing, I had him double check my edges to see if they were soft enough. I was told they were not (kind of a bummer, I must admit; I had worked so hard on perfecting the edges). So I spent about half an hour reworking the sides and edges.

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Teachers College, 525 W 120th St, New York, NY 10027

Subject: Cleaning my zinc plate

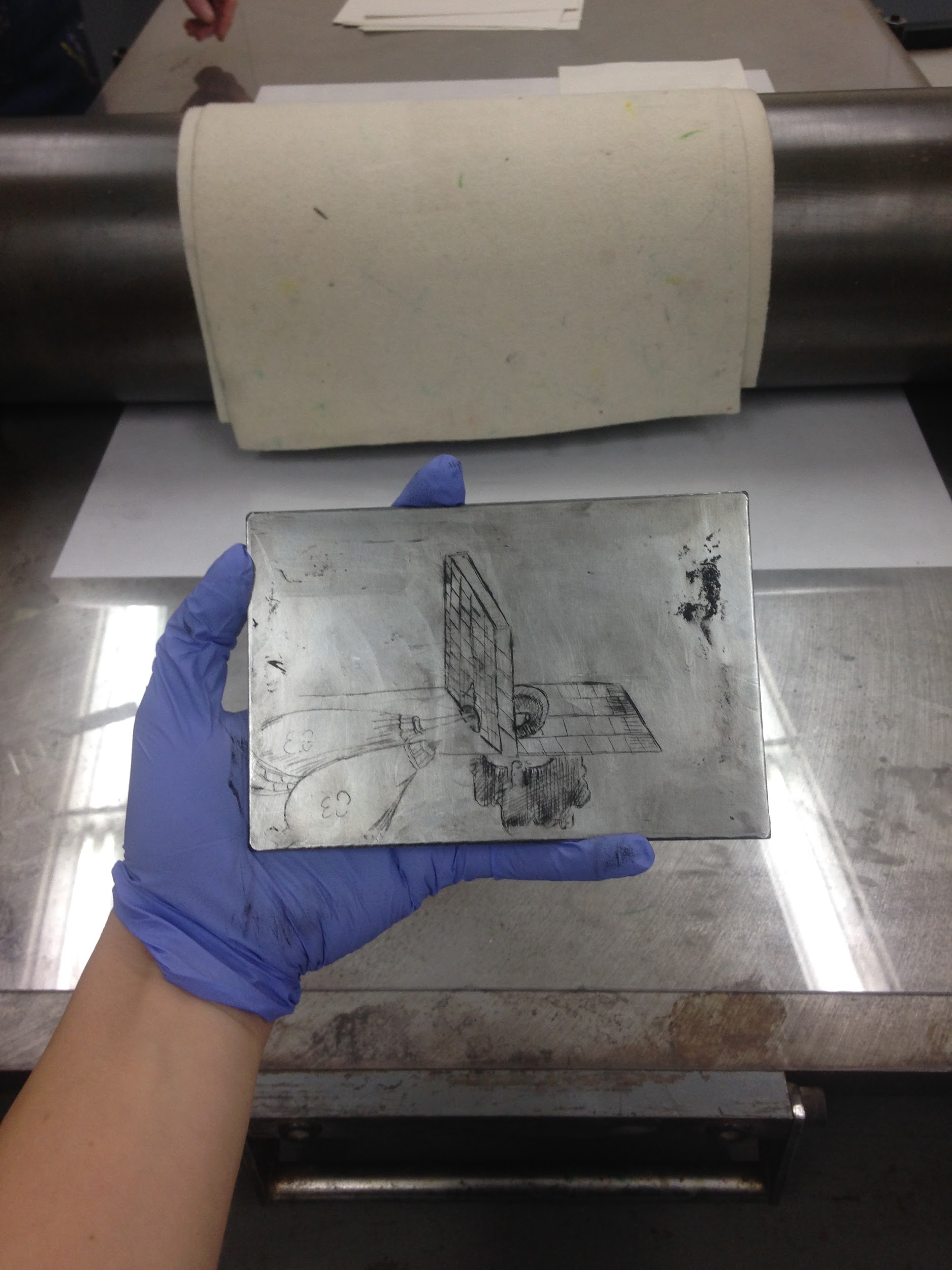

I cleaned my zinc plate of fingerprints and grease with etching polish and soap and water (while wearing gloves). I dried the plate with paper towels and put it aside.

Name: Celine Camps

Date and Time:

Location: Teachers College, 525 W 120th St, New York, NY 10027

Subject: Printing

Tools and Materials:

Zinc plate

Oil-based printing ink

Nitrile Gloves

Apron

Putty knife

Newspapers

Sheets of newsprint paper

Pieces of Cardboard for scraping and dividing ink

Old small pieces of soft cloth

Dampened 17th century paper (from the Iowa Center of the Book)

Dampened Watercolor paper

The intaglio printing press

Two sheets of felt (which are part of the printing press)

A bin

Soy solve

Water

Soap

The Printing Process

The first step in the printing process was to cover the tables with newspaper. We were going to use oil-based ink, which causes stains that are difficult to remove. Hence also had to wear an apron and nitrile gloves.

Check the pressure of the press.

I had no clue how to determine this and even after having printed I found it hard if not impossible to say if there was enough pressure. I relied entirely on the expertise of Caroline and Ad.

N.B.: Always make sure you have a bin at your disposal (that is not full) so you can easily dispose off pieces of paper, newspaper or gloves covered in ink.

Place your zinc plate on top of a sheet of newsprint paper (resting atop the newspapers)

Remove the ‘skin’ of the ink, as this will not ink (image 1).

Scrape the ink out of its packaging with a putty knife. No digging (quoting Ad: anyone who diggs, pays for the ink) (image 2)

I noticed it helped to tilt the can of ink so as to make the scraping easier.

Dab the ink onto the plate (image 3)

I found it difficult to tell how much ink to use. Since some students had already done this before I started, their experience allowed them to recognize how much I would have to use. As with so many elements of making processes, this too was a matter of learning by doing.

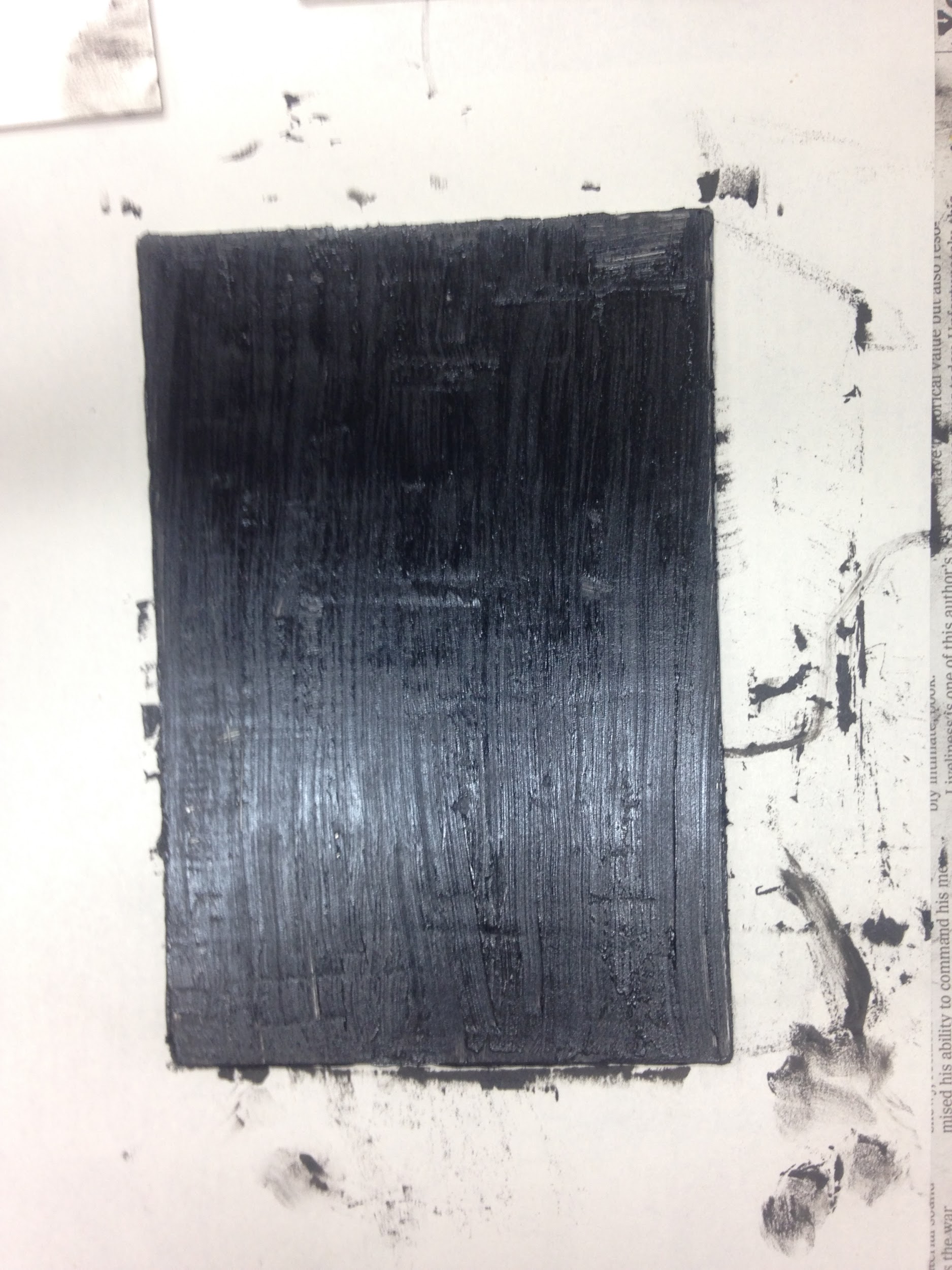

Divide the ink over the plate with a cardboard scraper, moving it both horizontally as well as vertically over the plate. Make sure the entire surface is covered in ink (image 4).

I was surprised to see how little ink you need to cover the plate. Because the ink was so pasty (and not liquid at all), I assumed more ink was needed. But it turned out you need rather little ink to work with.

To make sure you have an even layer that you can press into the grooves, use a piece of old cloth, shaped into a tiny ball) to rub (in a circular movement) over the plate.

Take a piece of newsprint paper and place it on top of your place. Press it down with your hand and gently dab it with the palm of your hand (serving as a cushion). This in order to remove excess ink. Repeat this for about 3-4 times.

Fold a piece of newsprint paper and place it on your plate with flat fingers (do not press your fingers into the plate as this will remove the ink from the grooves). Remove the ink from the relieved areas of the plate (leaving the ink in the grooves) (image 5).

I found this rather tricky. The piece of paper stuck to the ink, making it hard to move it across the plate. It took some time to find out how to get a grip on the paper, without pressing my fingers down onto the plate. It got easier once there was less ink on the plate.

I also wasn’t sure how much to actually clean the plate -- no one else seemed to know this either, except for Ad. Experience is key here yet again.

This took quite a bit of time

N.B. do not forgot to clean the edges of your plate as these will otherwise show on the print.

Make sure you have no ink blobs on your plate (image 6).

Because I still had various ink blobs on my plate that were difficult to remove, I had to use the piece of cloth again to spread it out over my plate.

Then I used a new piece of newsprint paper to remove the remaining ink (except for that in the grooves).

Get ready for printing (image 7).

Ad told me I had cleaned my plate too much and that there was not enough ink in the grooves left. I thus had to re-ink my plate.

Imagine not having had an expert print maker around: I am not sure I would have been able to immediately connect the dots. I.e. I doubt I would have connected the shallow print with my having cleaned the plate too much.

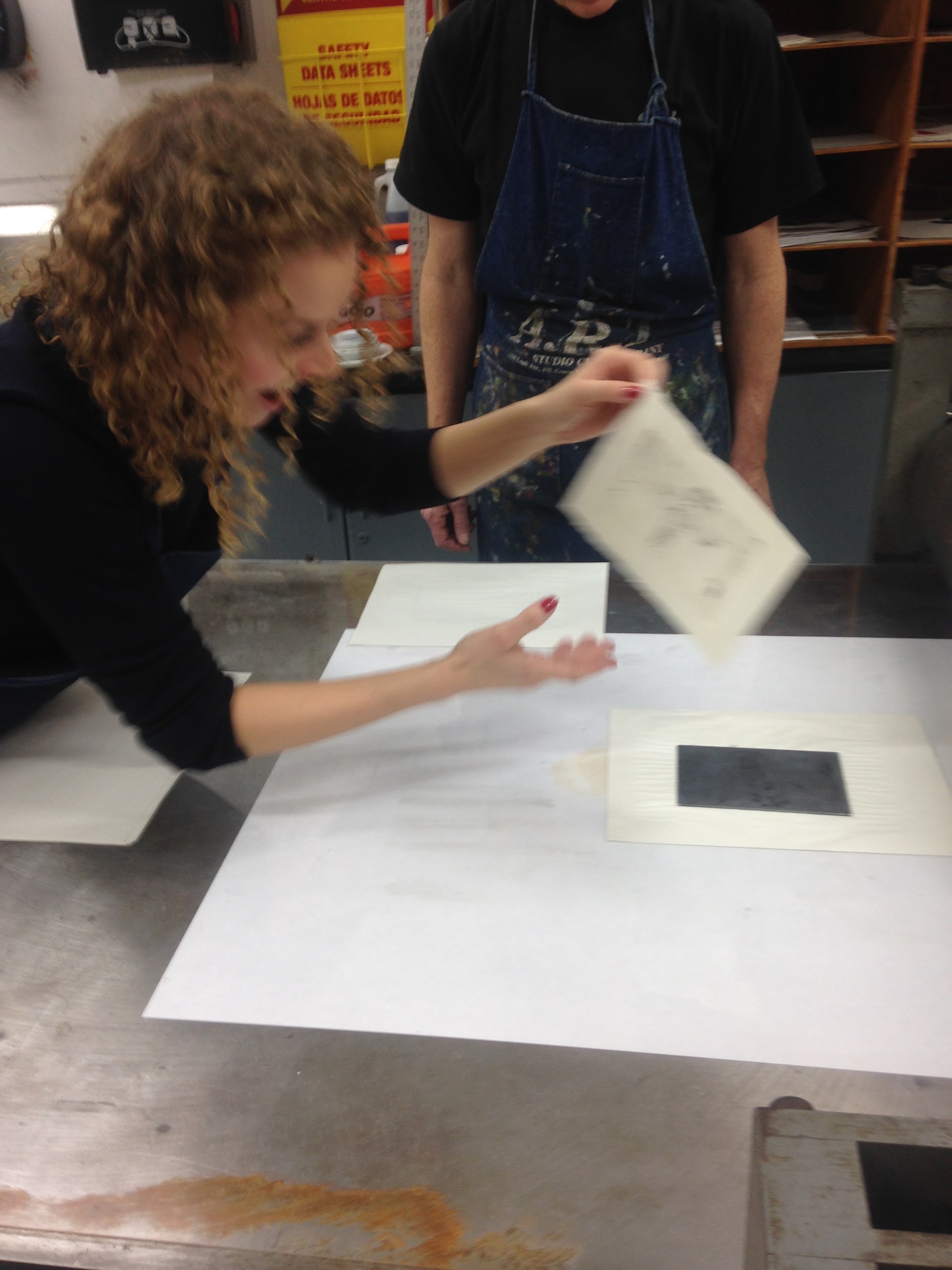

Go to the printing press. Place a sheet of newsprint paper on the bed of the press. Let the plate drop on top of it so as to not smudge it.

Remove your gloves and wash your hands (if needed)

Collect paper -- choose either the watercolor or the 17th century paper (image 8).

I was most curious about the early modern paper, particularly because I had an ink drawing of Ms. Fr. 640 and I wanted to create an ‘old’ effect (if possible).

Take one sheet of paper out of the packaging. Make sure it is damp enough. If it is too wet, remove excess water by placing the sheet between to towels and gently rolling over it with a rolling pin (image 8). N.B. make sure to close the wet package again once you’ve taken out a sheet of paper.

Place the paper on top of your plate (image 9)

Pull the edges of the newsprint paper (with the zinc plate and printing paper on top) towards the end of the roller press (image 10)

Place another sheet of newsprint paper on top to prevent any ink from staining the felt.

Place the two sheets of felt on top (image 11).

Run your hand over the felt, feeling the zinc plate, making sure there are no air bubbles and the paper sticks to the plate properly.

Roll through the press by pulling on the turning wheel (image 12).

You will feel a kickback once your plate moves through the press.

Once it was my turn to print, I had already forgotten about the kickback and it scared the living hell out of me -- I initially thought I had done something wrong and ruined my plate.

Stop pulling once the felt is almost entirely underneath the roller press.

Your print will now be on the other side.

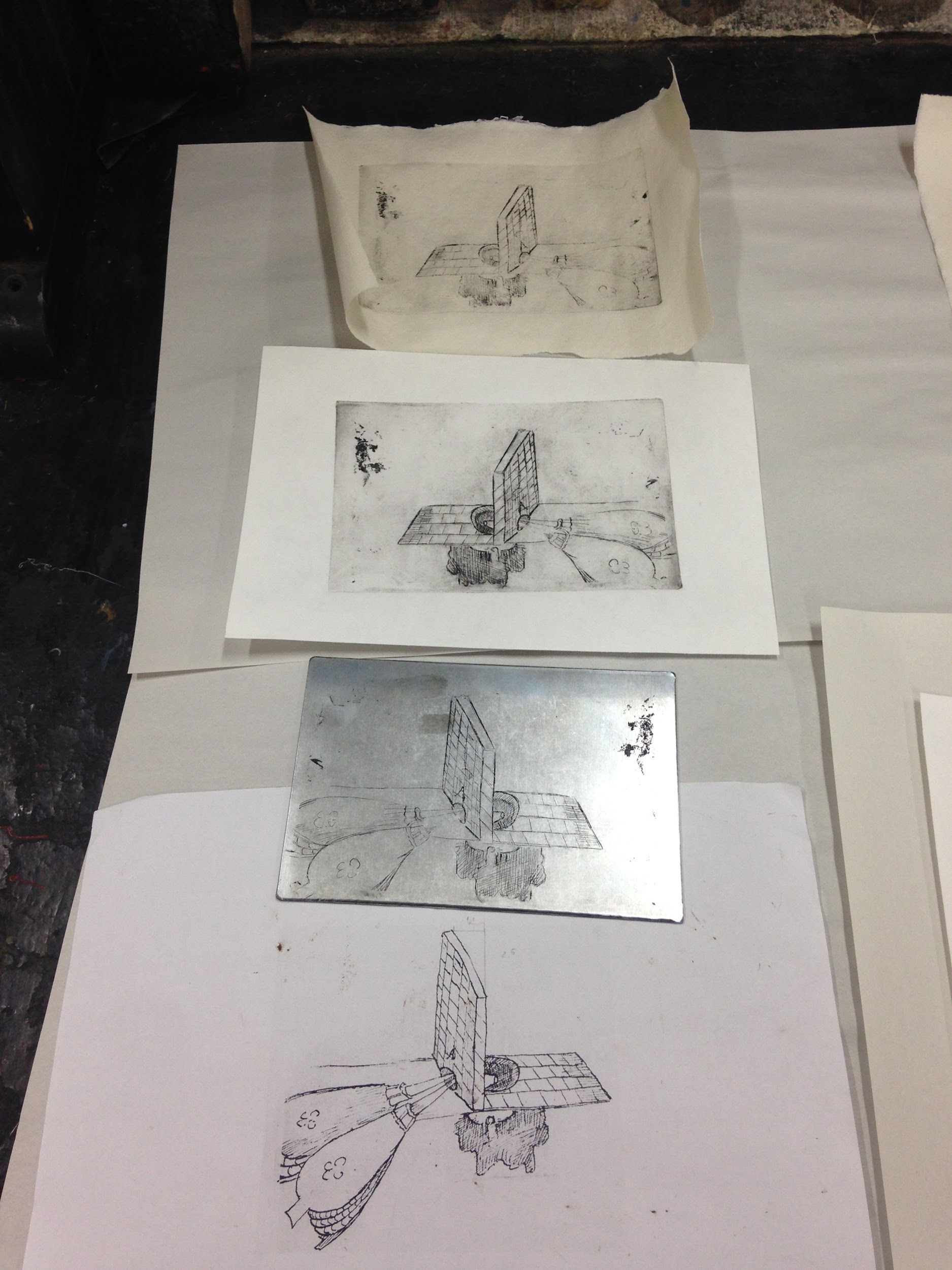

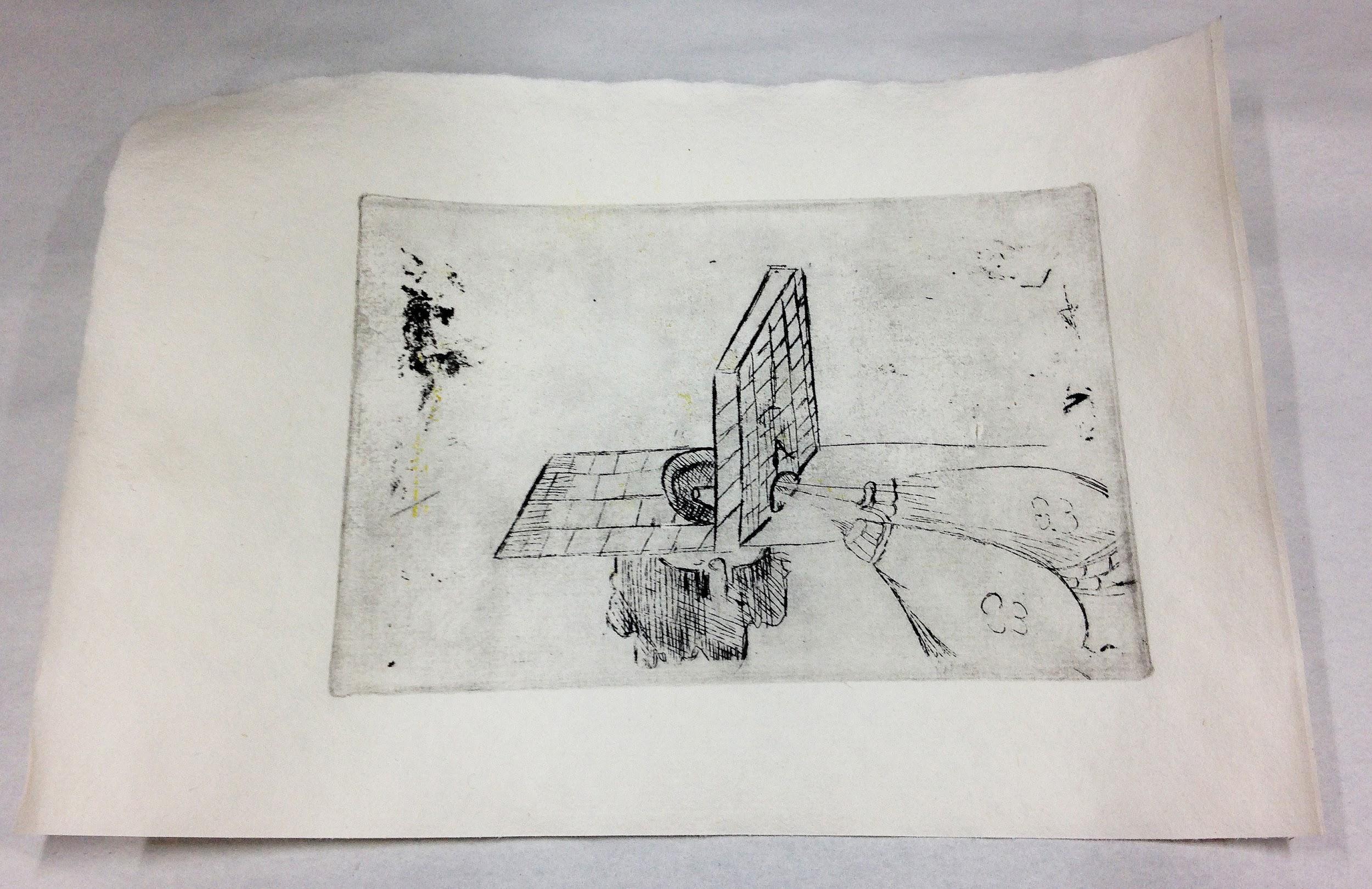

Remove the felt and the newspaper print and check your result (images 13-15)

Clean your plate with SOYsolve and soap and water.

Repeat

The result

My first print (on the 17th century paper) came out rather shallow, but I was extremely excited nevertheless. It was amazing to see that the grooves had still taken up and offset ink (despite my own expectations). According to Ad, other people had similar kinds of results (image 16)

It was hard for me to tell, however, if it was the paper, my having removed too much ink, or the grooves not being hollow enough.

This was probably something I had to figure out by experimenting and changing different variables each time. Unfortunately we could only use one

The foul-biting which had bothered me at first (after it had just come out of the etching bath), in fact gave the whole a nice ‘old-manuscript-looking’ touch and I was rather pleased with it.

On my second try, I used the watercolour paper, which created a much cleaner look and larger contrast between the ink and the lines (image 17)

As before, I am not sure if this is due to the paper, the amount of ink in the grooves, or their depth.

Because we had one 17th-century sheet of paper left at the end of the day and everyone had finished printing, Ad made another print of my zinc plate.

It came out almost perfectly and I was over the moon with the result (image 18)

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|