Table of Contents

Dark red text has been formatted as certain heading types. To ensure the table of contents is rendered correctly, make sure any edits to these fields does not change their heading type. |

Name: James Buckley

Date and Time: 2018.12.6, 11:48am

Location Laboratory

Subject: Tin

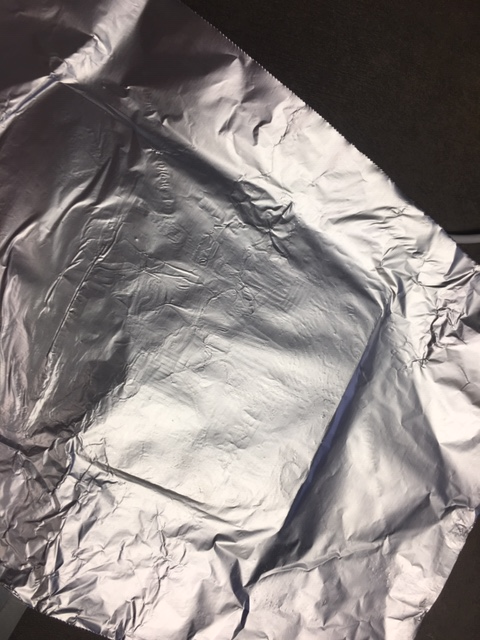

As the author-practitioner leaves the qualities of the tin used in this recipe somewhat vague, the recipe was tested by placing a sheet of aluminum foil over an etching and striking it with a hammer to see if this would produce results like those anticipated by the author-practitioner. The aluminum foil did indeed take on the imprint of the etching.

After this proof of concept, we then moved to melting tin. Initially, we started with two tin ingots in a casting ladle. Since the melting point of tin is a relatively low 231.9C, the ladle was placed on a hot plate. After approximately 25 minutes, however, the tin had only reached 229C and was not getting any hotter. Consequently, a decision was made to switch to a propane torch, despite fears that the propane might have some effect on the tin. Afterward, the tin rapidly reached its melting point and melted.

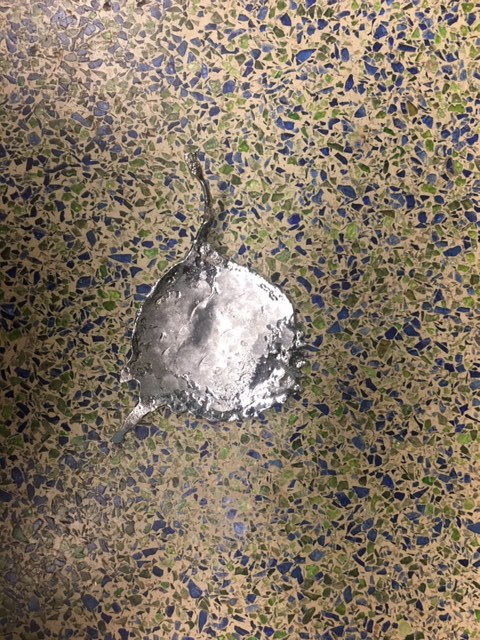

Once the tin had melted, I slowly poured it onto a marble slab and then lightly pressed a pinewood board onto it several times in order to flatten it. However, the tin cooled and solidified so quickly that it seems that only the initial press had any effect on the tin. Examining the tin, we saw that it had taken on a round shape and its surface was characterized by a large number of bubble marks, possibly from the cooling process.

Attempting the process once again, three ingots were placed into the casting ladle and melted with the propane torch. At the same time, the marble slab was heated by placing a bowl of boiling water on top of it in hopes that the tin would not cool and solidify as quickly. This time, the melted tin was quickly poured onto the marble slab and the pine board was placed down onto the tin only once but with greater pressure. As a result, the solidified tin seemed to be somewhat thinner and it also had splashes on the end that were extremely thin. Moreover, it had fewer bubble marks than did the previous tin.

Afterward, both pieces of tin were put on top of an etching, covered with felt, and hammered with a rubber mallet in an attempt to transfer the etched design to the tin. The first piece of tin showed only very light and incomplete evidence of the etched design. The second, thinner piece of tin seemed to take the design somewhat better. However, neither seemed to be adequate to the author-practitioner's purposes, suggesting either that both pieces were too thick or that insufficient force was being applied.

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Name: James Buckley

Date and Time:

Location: Laboratory

Subject: Tin and copper etching

Working on the hypothesis that the tin used in the recipe ought to be thinner than the tin that had been produced during the session documented in the above field note entry, I took the second piece of tin I had produced (since it was the thinner of the two) and attempted to hammer it out. Progress was very slow, but after around thirty minutes it was clear that the tin was becoming thinner. In an attempt to expedite the process, the tin was heated with a propane torch and then hammered. This seemed to have a limited effect, as the nature of the workspace in the laboratory made it necessary to first heat the tin in a fume hood and then remove it from the fume hood to hammer it. As a result, the tin seemed to cool before it could be hammered. Nevertheless, continued hammering produced a noticeable effect, as the tin expanded from an original 9.5cm to 10.8cm at its widest point after another 25 minutes of hammering.

This thinner piece of tin seemed to take the etched design better than it had before hammering. However, this result was produced with the use of an iron carpenter’s hammer rather than a rubber mallet. When this hammer was used on the first piece of tin—which had not been hammered out—it also produced a more noticeable design than had the rubber mallet, suggesting that the increased force of the hammer was as much responsible for the improvements as was the process of hammering out and thinning the tin. Nevertheless, the thinner tin did appear to take the design better than did the thicker tin and the hammering process also had the effect of eliminating the bubble marks in the tin, making it more suited to being used as an ornament.

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Name: (Also the name of your working partner)

Date and Time:

Location:

Subject:

Name: (Also the name of your working partner)

Date and Time:

Location:

Subject:

| Image URL: |

|---|