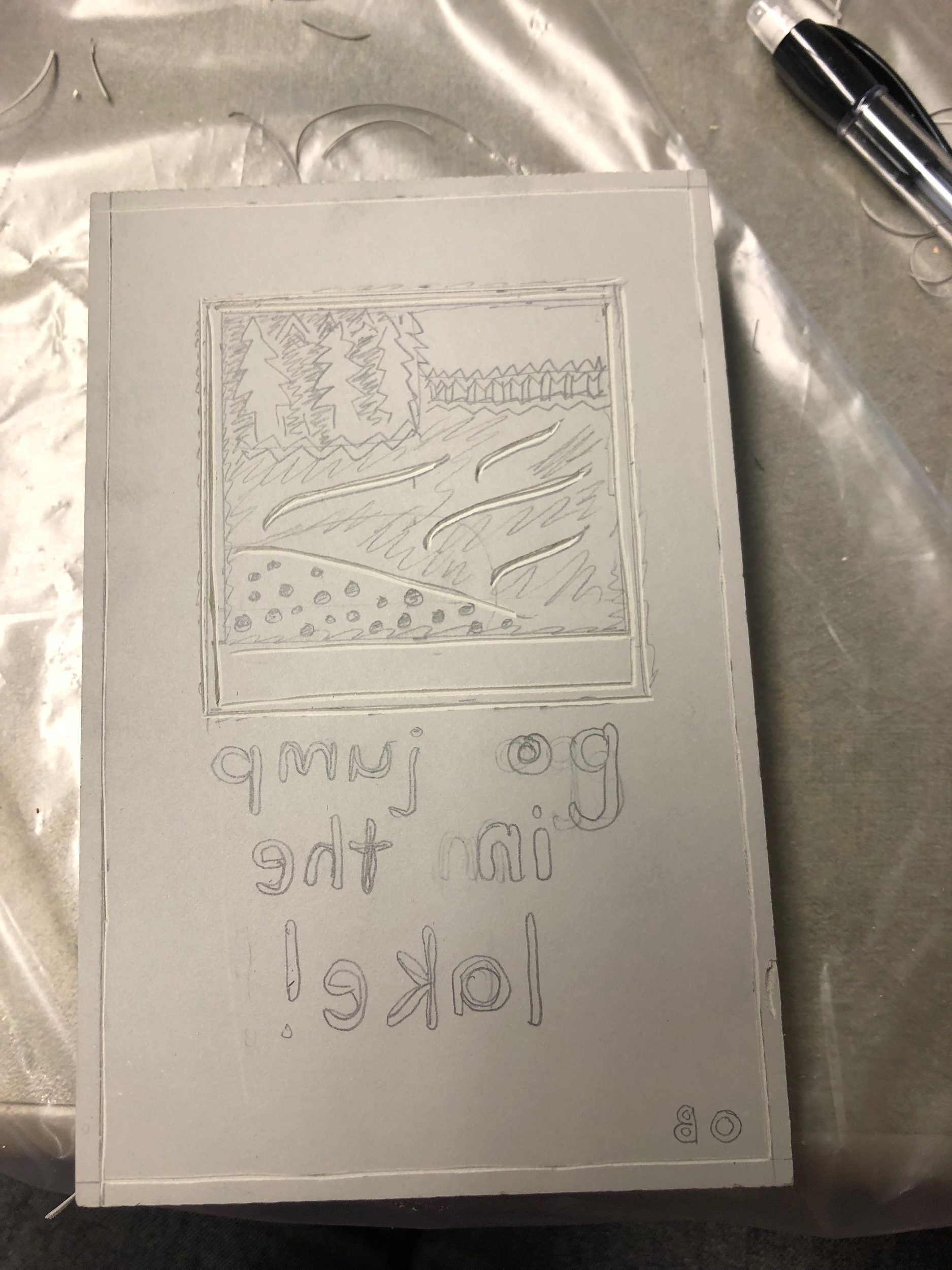

Block with sketch (notice problematic lettering)

Table of Contents

Dark red text has been formatted as certain heading types. To ensure the table of contents is rendered correctly, make sure any edits to these fields does not change their heading type. |

Name: Olivia Branscum

Date and Time:

Location: Chandler 260

Subject: Linocut

Materials:

1 linoleum block, 4x6” (Making & Knowing Lab)

1 Speedball linocut handle

1 #1 Speedball tip

1 #5 Speedball tip

Plastic (M&K)

1 HB pencil

I expected the process of preparing the linoleum block to be much easier than it was in practice. I’ve played with linocut before, but it’s been years since I worked with the medium; I remember feeling extremely frustrated by the stubborn linoleum and the way my knife alternately refused to budge the lino and skidded around the block. Still, I entered this phase of skillbuilding with confidence – since I’ve done some printmaking since I last tried linocut, I thought my skills would be equal to the linoleum block this time around. While I ended up finishing a block with which I am reasonably happy, the process was something of an arduous one.

I arrived in the lab and, after acquiring my handle and gouge tips, promptly attached one of the gouge tips incorrectly. It took me a few minutes to remove the gouge and start again. Then, I proceeded to grid out my block. So far, so good – I added an outline of my border to the block without any trouble. I soon encountered a problem, though: I started to remove the border, when we were actually meant to maintain the border and remove any negative space inside of it. Already, I was having a bit of a hard time ‘thinking in reverse’ by conceptualizing negative space as the ‘target’ of mark-making. Luckily, Tillmann intervened before I removed by entire border; in fact, since it’s harder to cut linoleum than one might think, I had barely succeeded in removing any of it before he caught my mistake! Since my design involved both outlines and solid objects, I tried to incorporate this experience into my plan by marking out the fields of lino that needed to be removed before making any cuts on the inside. While this idea was a good one in principle, I ended up departing from my preparatory markings because many of them turned out to be incorrect. Nevertheless, I think it was beneficial to spend a few minutes strategizing my positive and negative space in the image I chose, which was transferred to the plate using freehand drawing.

In addition to the inclusion of outlines and solid objects, my design included text. Without realizing it, I suppose I was setting myself a ‘skill builder’ for conceptualizing relief processes by including different kinds of impression-making approaches in the design. I sketched the words onto the block without any trouble (or so I thought), and began cutting away.

The actual process of cutting was simultaneously materially difficult, physically challenging, and somewhat addictive. Once I got the feel for removing excess linoleum from the block, the material difficulty reduced, creating space for physical challenge to enter the picture. As my hand and arm got tired from applying relatively consistent pressure and swiveling the block, I began to get more and more engaged and invested in carving out the block. While at first I felt stiff and afraid of hurting the block or design somehow, as I got used to removing material from the block, I developed a feeling of flexibility and fluency with the material. I was feeling great!

Suddenly, I noticed that two of the letters in the textual part of my design had been rendered so that they would print backwards (i.e., I did not reverse the letter forms in my mind as I had believed in order to print correctly readable letters). Because I had already removed much of the linoleum, there was no way to fix the ‘g’ and ‘j.’ At first, I felt very upset: it seemed like my block was ruined, when just a few minutes earlier I had been confident in my linocut skills.

In the end, I decided to cut away the word ‘go’ entirely (the ‘g’ had been rendered backwards) and remove the curve on the tail of the ‘j’ in ‘jump’ (which was also compromised). While the composition wasn’t as balanced as I had planned for it to be, I couldn’t complain about the results. At least I caught it before trying to make an impression with the block.

After resolving the issue with the text, I resumed work on the rest of the image. As has often been my experience during reconstructions, I fell into a sort of improvisatory state and found myself making intuitive changes to my process and design. It became clear that although I hadn’t thought through every element of my design beforehand – how, for example, was I going to render the different textures on the rock, water, and shoreline sections of the ‘polaroid?’ – it wouldn’t have made sense to stick to a plan that was devised before working with the block itself anyway. Once I had the opportunity to make cuts and marks in the block, the possibilities (both in terms of the material limitations of the medium and my skill level in its manipulation) made themselves clear in a way that I did not anticipate and which is difficult to describe. Since I have an art background, I know a bit about that shift from intellectualized, linguistically-bound planning stages to what happens when you actually get into collaborations with the material. In this course, though, things feel a bit different; the objective has shifted. I’m not learning a process in order to strategize the execution of my own projects – I’m trying to recreate a process as faithfully as possible to gain a different kind of knowledge, i.e. historical knowledge. Maybe it’s fair to ask whether this ‘historical’ knowledge is really so different from the practical knowledge gained in an art or design context after all. Maybe both kinds of knowledge are made manifest in this process.

At any rate, I found myself comfortably working the block, taking advantage of the somewhat slippery plastic cloth on the lab table to help me maneuver around my design. A couple of minutes later, Sophie and Tillmann announced that it was time to start cleaning up in earnest. Since my design wasn’t completed, I checked out a handle and two blades, bagged up my block, and brought it home with me.

| Image URL: |

|---|

Block with sketch (notice problematic lettering)

|

| Image URL: |

|---|

Block in process of correction |

Name: Olivia Branscum

Date and Time:

Location: 530 Riverside Drive, Apt 3C

Subject: Linocut

I was finally able to work on my linoleum block again today. Since I was finishing up my engraving and etching designs as well, I was in a much less perfectionistic mindset today than I occupied last time. This gave me more freedom to experiment with textures in the figural part of the design; other than that, all I needed to complete was the text. Today, I found it much more difficult to carve away the text than I did last time. I’m not sure why, but I think my home environment – which lacks a large table covered in sheet plastic – might have played a role.

When I finished carving my block, I returned it to the Ziploc bag and prepared to take the matrix to class on Monday.

| Image URL: |

|---|

Completed block |

Name: Olivia Branscum

Date and Time:

Location: Teacher’s College printmaking workshop

Subject: Linocut

Time flew in the print studio today! I got so engrossed in working on my etching and engraving plates that I did not get a chance to print my linoleum block.

I hope to be able to print it before the end of the semester. For now, I’ll have to accept that I may not be able to see this project through to its ‘conclusion’ in the form of an impression. Of course, this raises a question – what constitutes the endpoint of an iterative process like printmaking? What would happen if I treated the block itself like a final product, or used it for some other purpose? In fact, the recipes in BnF Ms. Fr. 640 that involve printmaking and impression-oriented processes often seem to be exploiting the wide variety of ulterior purposes of which print matrices and impression-making techniques can admit. In an oblique way, maybe I’m participating in that tradition by allowing impression-making processes to be something other than instruments in the making of two-dimensional images.

| Image URL: |

|---|

|