Table of Contents

Dark red text has been formatted as certain heading types. To ensure the table of contents is rendered correctly, make sure any edits to these fields does not change their heading type. |

Name: Katie Bergen

Date and Time:

Location: Chandler 260

Subject: Begin linocut

To begin this linocut, I brought in a drawing of a dog to trace that I had found on a website for beginning printmakers. After transferring this image to the lino block by tracing over paper with graphite applied to the back, I began to make incisions with the thinnest gouge available. It took some getting used to in order to remember to work away from my fingers at all times, and the lesson only really sank in after the gouge had done the same into my left index finger. Still, I found that working carefully around the outlines of the image began to produce useful results.

Name: Katie Bergen

Date and Time:

Location: Apartment

Subject: Working on linocut, gridding woodblock

I brought my linocut and woodblock with me out of town. I had gridded the woodblock on the evening of Wednesday October 10. It took about two hours and required careful measurement. Because the woodblock was a square inch bigger in each direction than the provided drawing, I created a half-inch margin around the final grid. The only problem I ran into was attempting to find a dollar coin to measure the target shape for the bottom left corner of the design. I ended up approximating the size with a bottle cap, and learned later from one of my colleagues that the vending machines in the basement of Fayerweather give change from a $5 bill in dollar coins. In any case, I was happy with my approximation.

I found myself nervous to use a larger-sized gouge on my linocut. Although by this point I had mastered working carefully and slowly with the fine gouge, I was occasionally still jumping the gouge at the ends of lines. To my surprise, using the larger gouge was much easier to use than doing the fine detail work with the fine gouge. I had thought that a larger gouge would give me less control, but working in larger areas allowed me to get a better feel for the shape of the tool and the ways that different angles produced differently shaped grooves in the lino.

Name: Katie Bergen

Date and Time:

Location: Chandler 260

Subject: First session with Ad, introduction to copperplate engraving, woodblock carving

This day’s class was the introduction to copperplate engraving and woodblock carving. I found myself intimidated by both processes, and was happy to have clear instruction from Ad on how to proceed. I had not realized it was important to cut lines around the design of a woodcut before gouging, but it made sense that those cuts would help guide and stop the gouge when carving larger areas. The copperplate engraving certainly had fewer steps, and it was clear to see the effect of practice and “embodied knowledge” as Ad worked with the burin.

My attempts to emulate him were unwieldy, which was only to be expected from a pure beginner. The burin is a delicate tool, and I found it was small for my hand, or at least my fingers had trouble staying in the correct position. I didn’t feel as though my wrist had enough room to lower the angle enough to get a good “bite” into the surface of the copper. I found myself wondering about other engravers past and present, who certainly might have had bigger hands or longer fingers than me. How was the burin developed as a tool? How was proper hand-shape determined? Any person using a tool must marry the safest and most effective body posture to the particular needs of their particular body. In short, surely every person engraving with a burin had felt the same frustration I was feeling at some point in their training. Was it right for me to let my hand assume a posture that was comfortable, if not correct, as long as it was safe? Or was it better to force myself into the prescribed position and hope that comfort would come with experience? Anyone taking instruction on an unfamiliar task asks herself the same question. Still, I managed to achieve a few copper curls and shaky engraved lines.

Name: Katie Bergen

Date and Time:

Location: Chandler 260

Subject: extra skillbuilding sessions in copperplate engraving, woodblock carving, application of etching ground

I was able to come in this week on Tuesday and Thursday to continue to work on copperplate engraving and woodblock carving, but the priority was applying etching ground to my zinc plate. I spent twenty minutes assiduously polishing this plate with little effect only to realize that the plastic protective film had not been removed, and the work had to be done over. For the rest of Tuesday, I worked on copperplate engraving, which I continued to find difficult, and woodblock carving, which I was surprised to enjoy. The comparative heaviness of line in many woodblock prints suggested to me that woodcarving is necessarily a more awkward, clumsy, difficult process than copperplate engraving. This may be the case for those who are practiced at engraving, and it may have been true for those who adopted intaglio printed during the time the manuscript was being written. For me, however, wood carving is much more intuitive and forgiving than working in copper. Still, the fine detail of the gridded block was not served well by my large gouge, and the design suffered as a result. The texture of the wood felt pleasantly malleable under my hand, most likely due to the sharpness of the gouge and knife I was working with. It made me consider how the selection of recipes in the artist-practitioner’s manuscript might have been curated not just by fashion, ubiquity, or remunerative potential, but by pure preference. Were artisans of the AP’s time known for their preferences for certain types of work over others? Would one have been known as a master life-caster, and another as an expert in stucco molds? Or would there have been an expected competency across techniques?

On Thursday I was able to polish my zinc plate correctly, degrease it with acetone, and apply etching ground to it. Holding the zinc plate with pliers above a hot plate in the fume hood, I waited for it to heat to an appropriate temperature by dabbing it periodically with the small smooth lump of etching ground. The ground was composed of a compound of tar and pine resin which slowly moved more smoothly over the zinc, until it was able to glide instead of skipping, leaving a smooth skid of liquid ground on the plate. At this point Ad guided me in skating the ground evenly over the zinc plate without applying too much. Then, I was instructed to use a feather to spread the ground even more thinly. This is the kind of knowledge that I think must only be able to be shared through one-to-one instruction. Ad had demonstrated the correct procedure for spreading the ground with a feather before we started, and there is no useful way to describe in words the precise way in which he held his hand and fingers, or the amount of pressure suggested by the precise bend of the vane of the feather as it passed across the plate. Additionally, expressing units of time through text would be imprecise in describing this process, because only by seeing it done by a master can one understand the quick, gentle movements necessary to push the liquid ground across the plate before it can set. Should it take three seconds? Four? There are signs by which to know if the ground has spent too long heating on the plate, namely the bubbles that appear in the ground, but by time those signs show up it’s a fait accompli, the time can’t be regained.

In any case, I was pleased by the result of my grounded plate and was able to scrape a simple design into the ground to be etched on the following Monday.

Name: Katie Bergen

Date and Time:

Location: Chandler 260

Subject: etching

A copper sulfate solution was placed in the fume hood, next to a pan of tap water. To etch the zinc plate, we first taped over the sides of the plate to prevent the acid solution from degrading the edges of the plate or causing any foul biting on the design. To this taped perimeter we attached a handle, also made of tape, to make it easier to retrieve the plate from the copper solution. As the plates sat in the acid bath, copper deposits formed along the exposed zinc. When the plates were exposed to air, those copper deposits would solidify and become difficult to remove from the plate. To prevent this from happening, we were instructed to brush our plates periodically, about once every minute, to remove these deposits from the lines that were developing. We were to brush with feathers, which curled over time in the acidic solution. A short period of etching was described as around 5 minutes, a longer period resulting in deeper lines would last 20 minutes or so. So, after the first 5 minutes of submersion and feather brushing, I removed my plate from the acid bath and rinsed it in the adjacent water bath. I then took the plate to the countertop, dried it carefully, and examined it.

Despite my brushing, there was a great deal of copper deposited in the etched lines of my plate. I also detected some foul biting occurring in the top left corner of my plate. Still, when I checked the depth of the etching with a drypoint needle, I found that the acid had bitten successfully, and deeper than I’d anticipated. I decided to tape over the outer margin of my design and re-etch the center of it, hoping to create a two-tone effect. I replaced my plate in the acid bath solution for a further fifteen minutes. As the area was crowded, I don’t believe I brushed the copper out of my etching lines as frequently as might have been advisable. Consequently, I removed my zinc plate at the end of fifteen minutes to find the lines nearly black with copper deposits. I rinsed the plate with soap and water and beveled it with the beveling knife, the scraper, and sandpaper. Of these three instruments I found the beveling knife to be the most intuitive and was pleased to pull curls of metal from the sharp edges of the plate. It took some instruction for me to understand how the edge of the plate should feel, but I ended up with a smooth result.

Name: Katie Bergen

Date and Time:

Location: Teachers’ College Printmaking Workshop

Subject: Printing plates

Tuesday morning I arrived late to the printmaking workshop at the Teachers’ College to begin printing my plates. With limited time and a subpar copper plate, I decided to spend my time printing my zinc plate and linocut block. After being instructed on how to ink and wipe the plates and run the roller place, I set to work inking my zinc plate. The copper deposits remained from the etching, but Ad advised me that it wouldn’t matter to the printing process. Scraping the ink from the surface of the pot was quite satisfying, reminiscent of attempting to preserve the aesthetics of a jar of peanut butter. It wasn’t necessary to use nearly as much ink as I’d imagined, and spreading it evenly over the plate required finding the right angle at which to hold the card in order to spread the ink without simultaneously scraping it off. I then used a roll of rag to press the ink into the etched lines of my plate using small circular motions.

After this, excess ink was blotted off the surface of the plate with a piece of newsprint. Because the ink was sticky, this created a series of abstract almost-prints on the newsprint as the excess ink was lifted off. When the surface of the plate was a flat matte black, I proceeded to gently pass a square of folded newsprint over it, holding the paper with thumb and pinkie finger across the flats of my fingers. After about ten minutes of this, the ink had come off sufficiently for the plate to be printed. I could clearly see my design, but I didn’t have a good idea of how much ink remained in the grooves.

Experiencing the printing process is what helped me understand how it became an iterative art form. Despite the amount of work that goes into etching a plate, creating prints invites experimentation. I can certainly understand how it would be possible to lose hours making small adjustments to the pressure of the press, the depth of the lines, the amount of ink or plate tone left behind after wiping. In this spirit, I decided my first print would be a trial effort to see how effectively my lines had been etched. I printed this trial on newsprint and was surprised at how well the image transferred. It was certainly not perfect by any means, but it preserved both a depth of color and fine detail that surprised me.

For my second attempt, I decided to print on the dampened high-quality wove paper. In my enthusiasm, I applied too much ink to the surface of my plate and consequently spent the next half hour gently wiping it off. The ink stuck to the plate in a pattern of Dalmatian-esque dots which stubbornly clung long after the rest of the ink had rubbed off. Finally, I resorted to scraping the spots off with a gloved fingernail, which would certainly have been frowned upon by Ad had he known. I suspected that my print would not work as well, but faced with the prospect of re-inking and undergoing another period of wiping I decided to go ahead and print. The lines in the plate did not look noticeably less dark than they had before, but it’s unclear whether I was looking at ink or at copper deposits left over from the etching. The second print came out much lighter and the design did not show nearly as well as the newsprint trial had. I was pleased to see no evidence of my illicit fingernail-scratching, but disappointed that I had wiped so much ink out of the lines of my design. Ad agreed that I had most likely over-inked my plate, but said that there was nothing wrong with the plate itself and encouraged me to find a printing workshop to allow me to refine my prints further.

Following this experience, I was pleased to be able to print my linocut block with relative ease. This process took place with a modern Speedball ink which was intuitive to roll onto the block using a roller. I made two successful prints of my linocut block and was very satisfied with both.

Caption: Finished linocut after printing

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

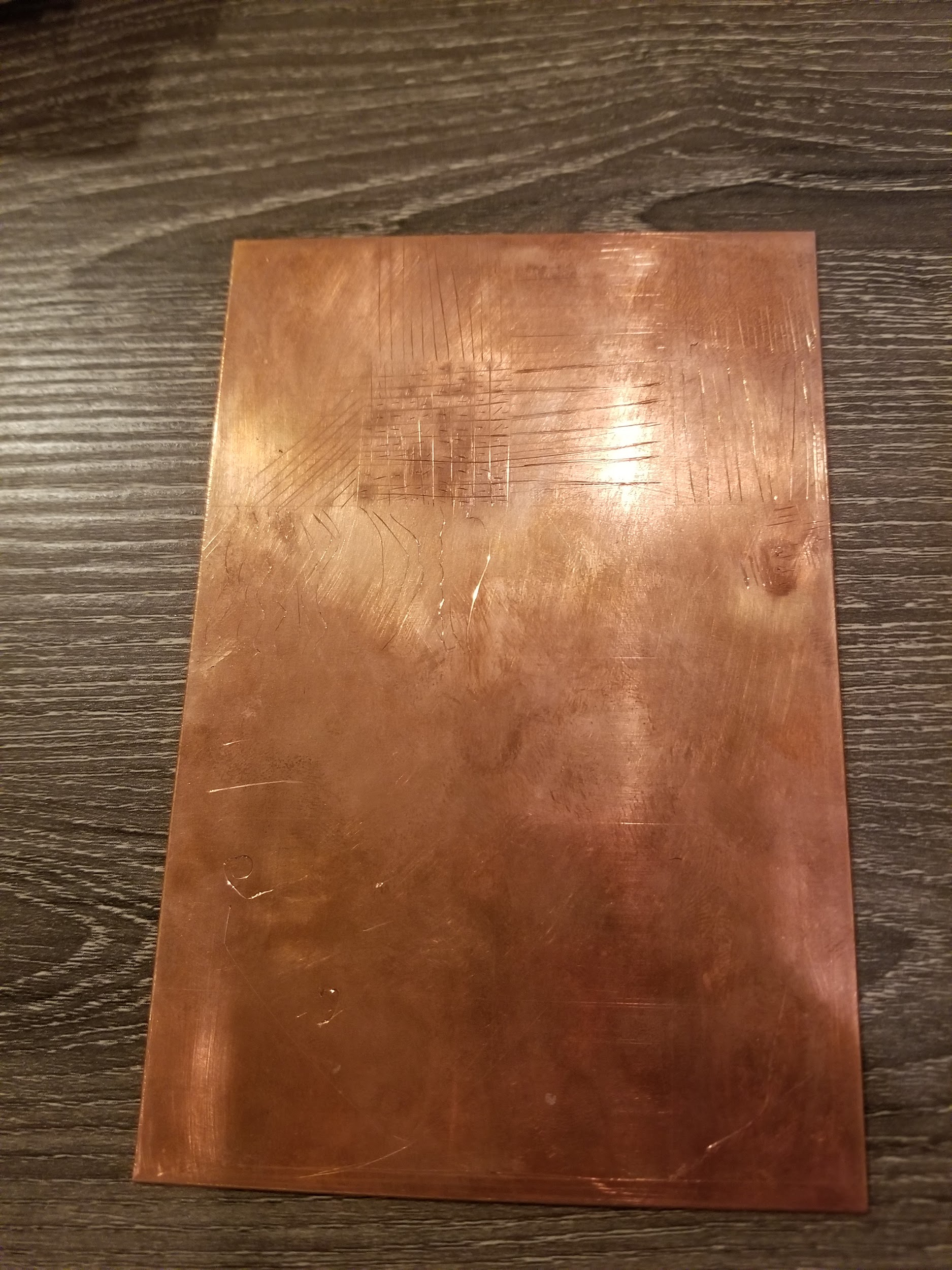

Caption: Copper plate

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Caption: A curl of zinc appears during bevelling

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

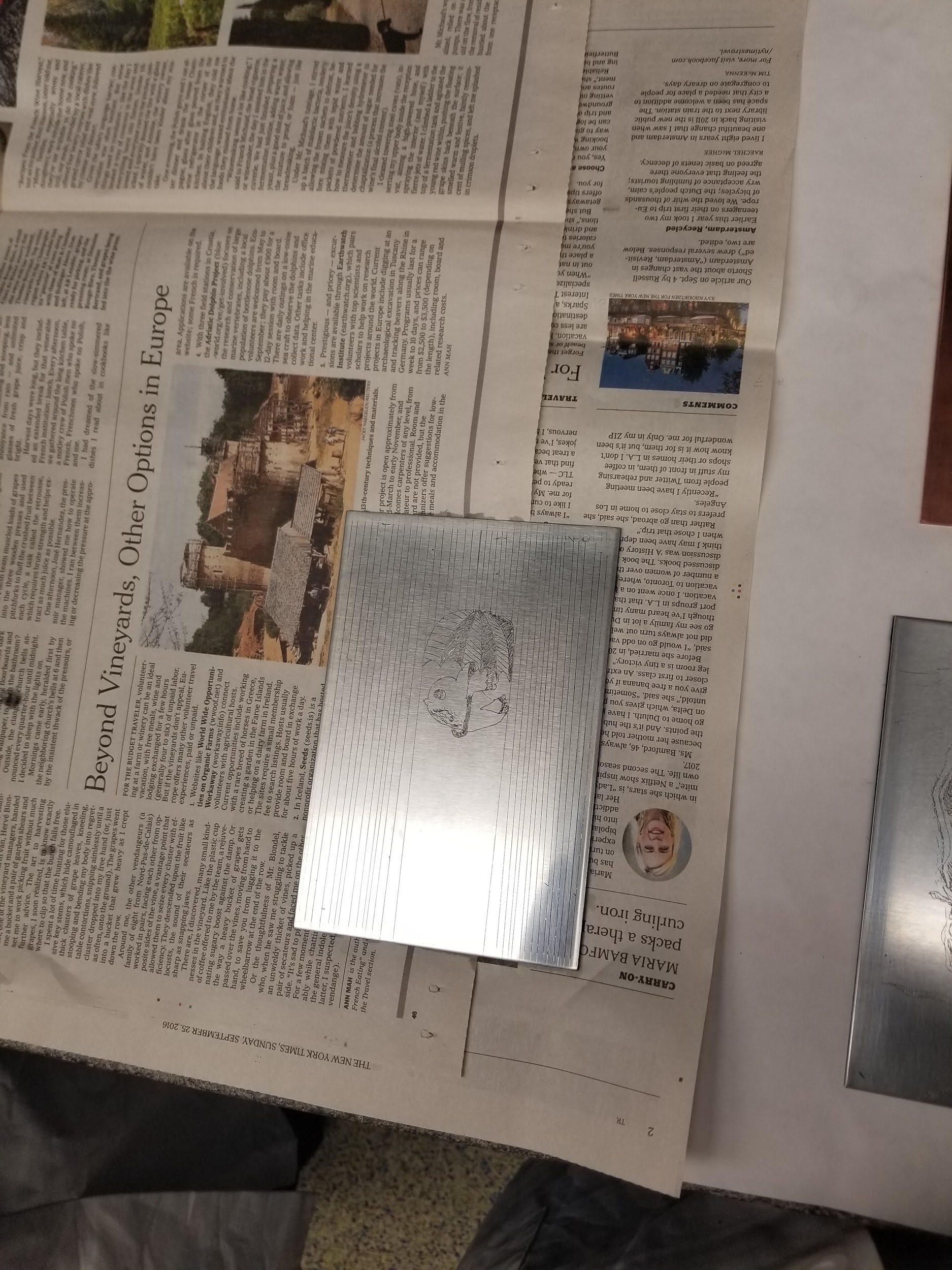

Caption: Zinc plate ready for printing

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

Caption: Zinc plate before etching, with ground

| Image URL: |

|---|

|

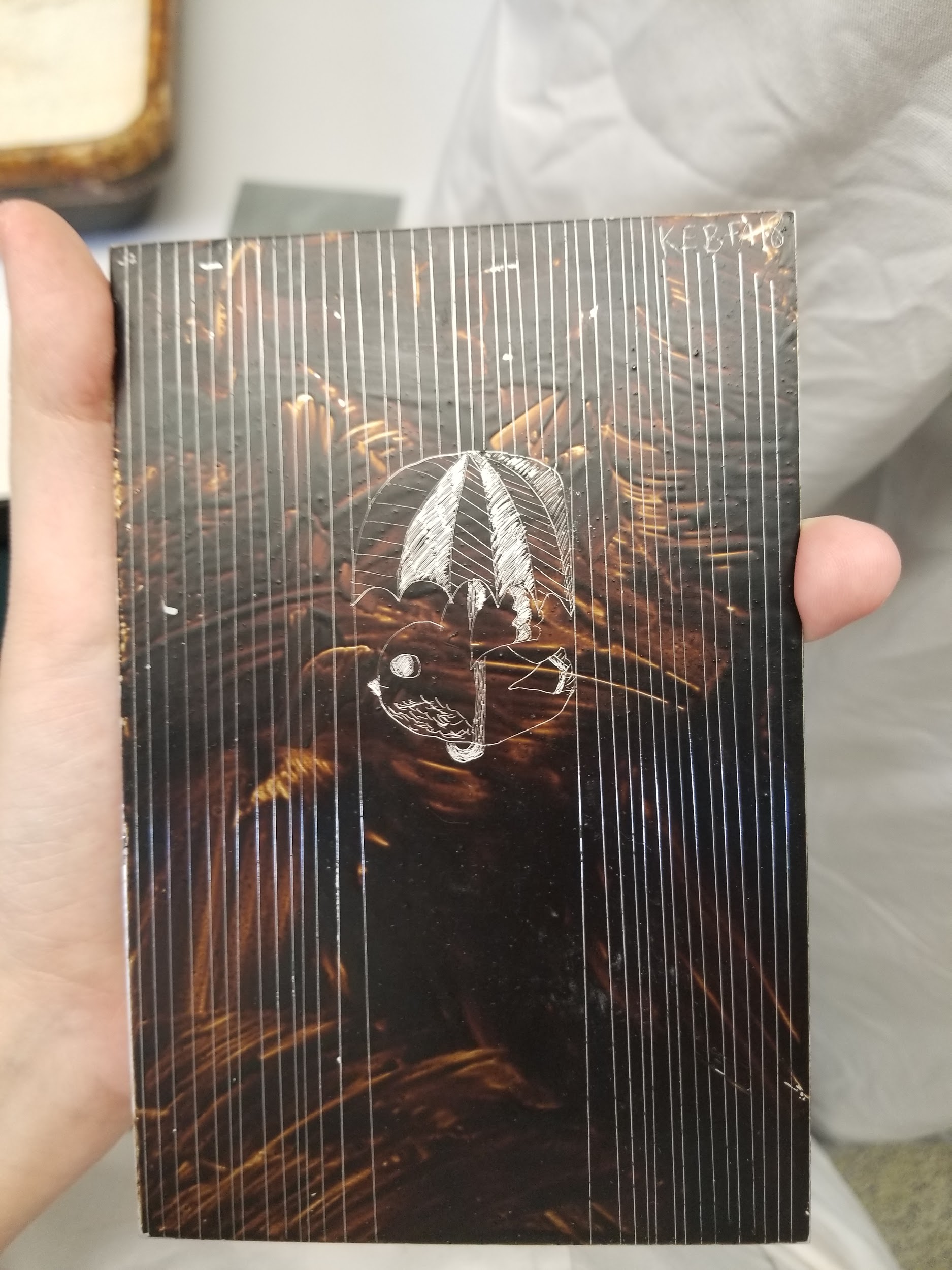

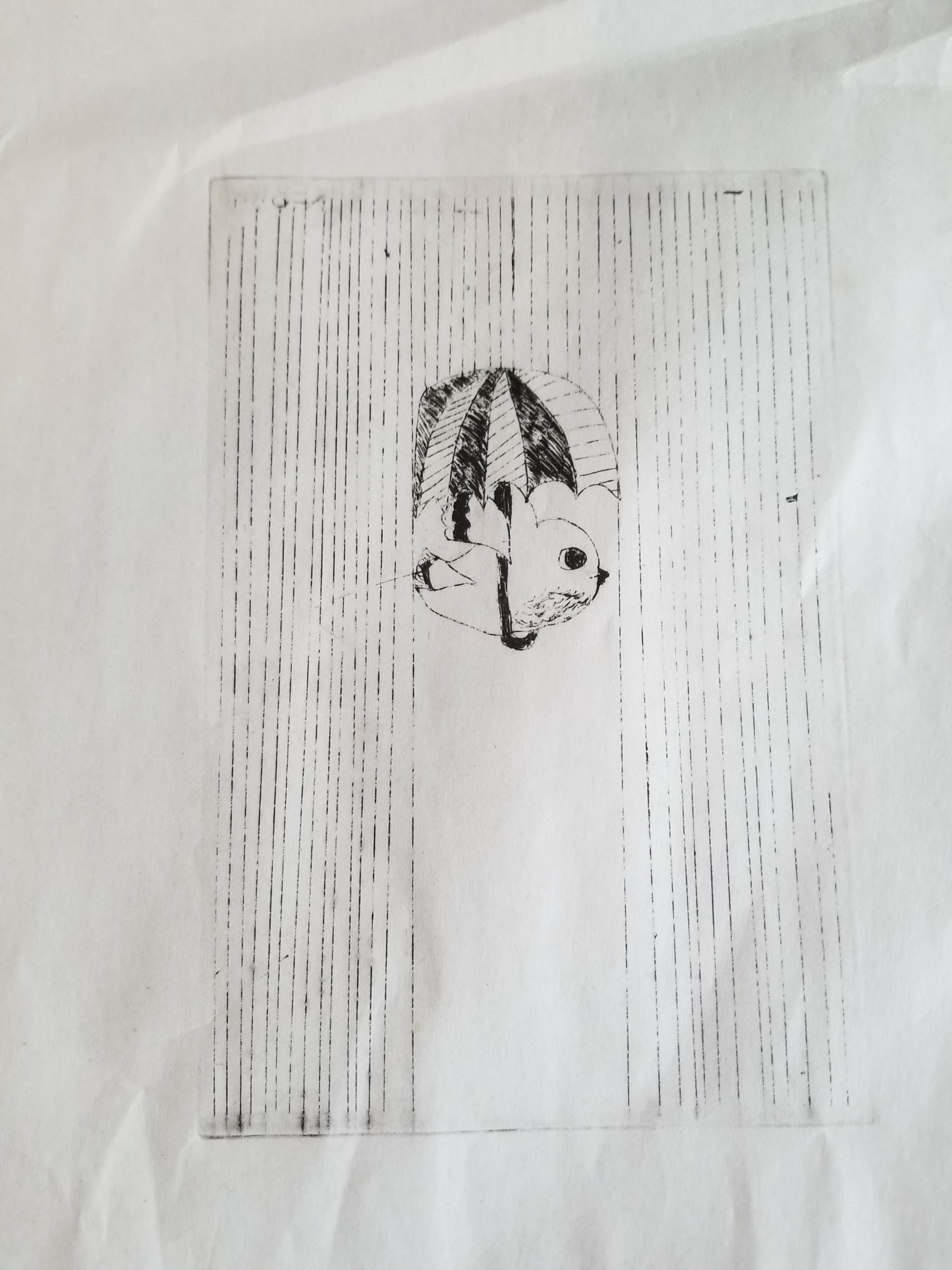

Caption: Newsprint “trial” print

| Image URL: |

|---|

|